Love Letter to Paris

By Roger Pines

(read time ~ 11 minutes)

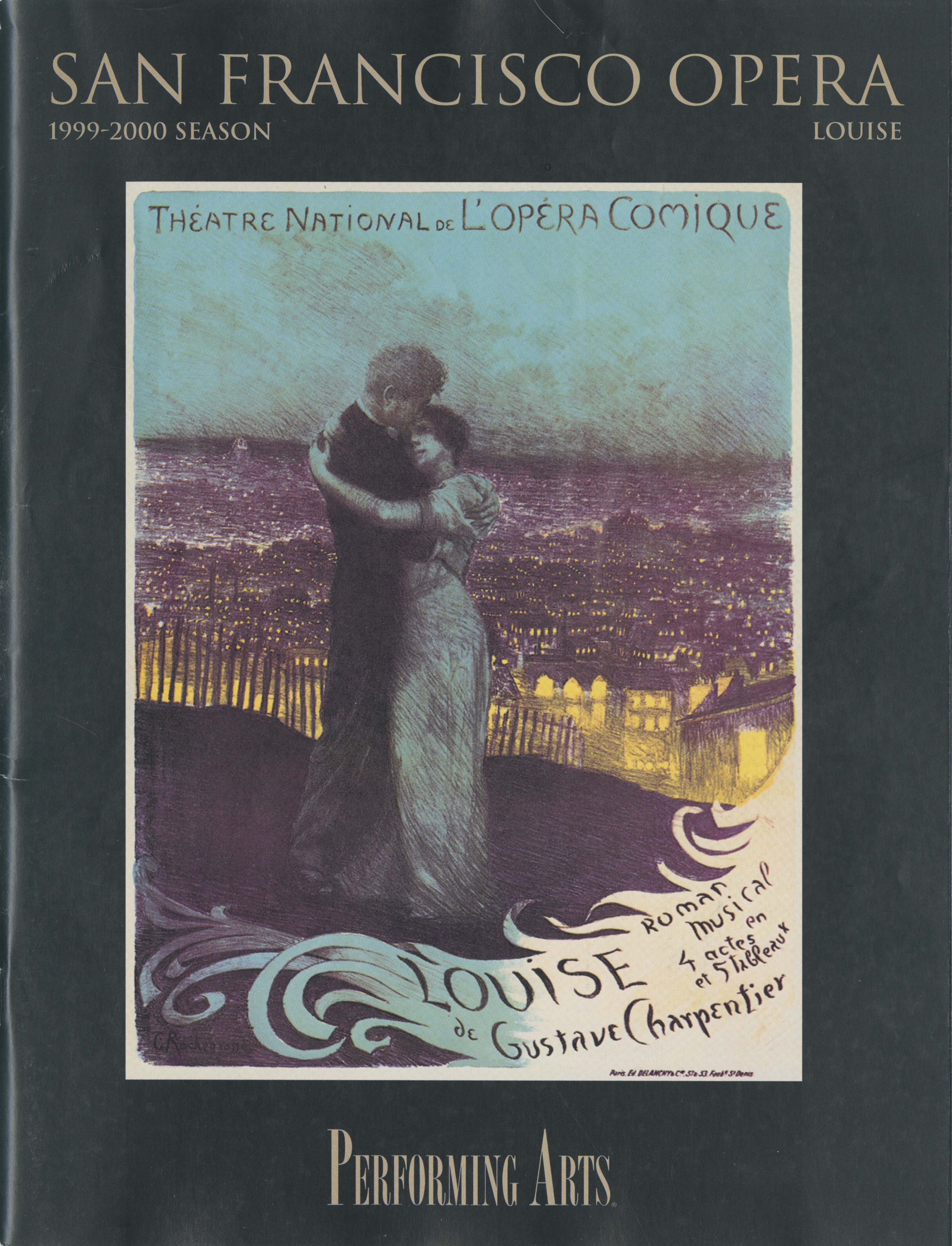

IN 1999 THE MOST PARISIAN OF ALL OPERAS, CHARPENTIER’S LOUISE, MADE ITS LONG-AWAITED RETURN TO SAN FRANCISCO, BOASTING A STELLAR CAST

Few operas bring a particular locale to life as Gustave Charpentier did in Louise. First heard in 1900, this enthralling work gives us a Paris that bursts with local color. Charpentier lived in Montmartre, and he knew the “feel” of its neighborhoods intimately. Listening to this opera, we can almost see the bustling streets and smell the café au lait.

Louise’s abundant appeal encompasses a great deal more than the score’s only familiar music, the heroine’s rapturous aria “Depuis le jour.” Charpentier intersperses dialogues between Louise and the other crucial characters—her lover Julien and her parents—with vignettes involving subsidiary roles, who give this opera its color and ambience. The majority of the cast’s 45 designated roles exude the spirit of Paris, so that the city essentially becomes a character in itself: a living, breathing community, as thoroughly believable as Catfish Row (Porgy and Bess) or The Borough (Peter Grimes).

Charpentier, who wrote his own libretto, was unusual among French opera composers of the time in focusing Louise exclusively on working-class people. That includes the seamstress protagonist, a heroine who has long attracted American sopranos. One of the early twentieth century’s greatest singing actresses, Mary Garden (Scottish-born American), who really put this opera on the map, has been succeeded by Grace Moore, Dorothy Kirsten, Arlene Saunders, Beverly Sills, Carol Neblett, and Renée Fleming.

Kirsten, a favorite diva in San Francisco for more than three decades, sang Louise’s 1947 company premiere and reprised the role seven years later. Following her in 1967 was the equally ravishing Saunders, leading soprano of the Hamburg State Opera. After waiting 32 years for another superb Louise, San Francisco Opera finally found her: Fleming (see sidebar below), whose role debut highlighted a burgeoning career that, a few seasons previously, had ascended from stardom to superstardom.

The unique warmth of Fleming’s vocalism is a joy from her very first entrance, shortly after the curtain rises. Later, in Act II, listen for one of many luminous examples of the soprano’s ease in floating softer phrases: Louise’s declaration to Julien, “Je serai ta femme” (“I will be your wife”). In that act’s final moments, note how a single word from Fleming—the spoken “Adieu!”—can convey both the anxiety and the excitement that Louise feels in leaving her job and her family to join Julien.

Fleming has everything for her role’s challenging second half. No doubt the entire audience was breathlessly awaiting Louise’s Act III aria “Depuis le jour,” already closely identified with Fleming in concerts, recitals, and on CD. Sopranos must negotiate the aria with the ultimate in musical and interpretive sensitivity, knowing exactly how to maintain a perfect balance between intimacy and grand-scale passion. Fleming accomplishes this ideally, letting every phrase radiate the ecstasy of the moment and crowning the performance with her resplendent leap to a sustained high B.

More thrills lie ahead with the “Libre! Vous êtes libre!” section of the extended love scene with Julien, where Louise is at her most vocally expansive. Here Fleming’s outpouring of glorious sound never becomes an end in itself, but rather delineates the character’s total capitulation to awakening love. Louise must throw caution to the winds in Act IV, as she explodes with a desperate longing to flee her overprotective parents and return to Julien. The finale gives us Fleming at her most powerfully dramatic, with both the technical security and the all-out abandon for what is certainly the most taxing portion of the role.

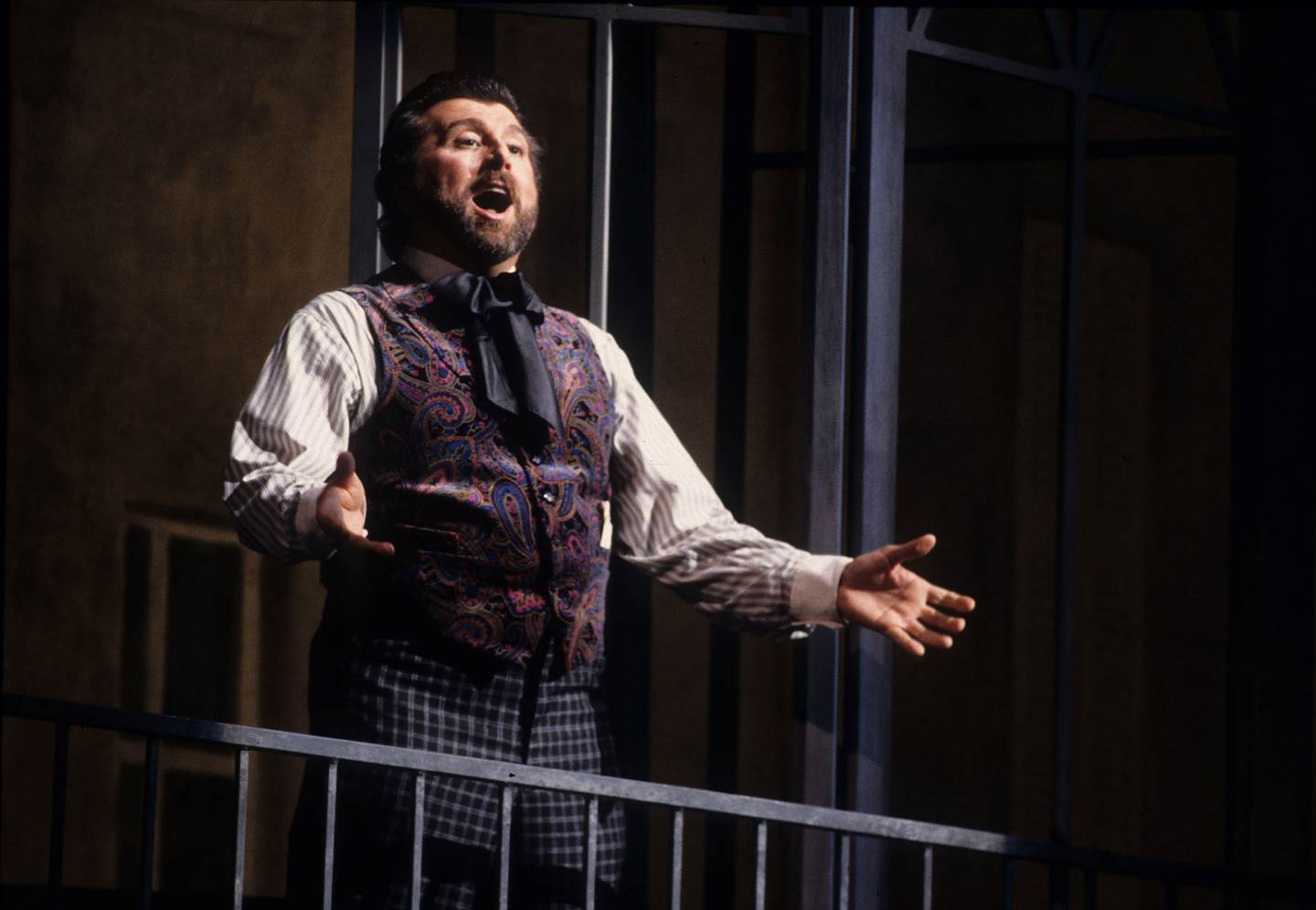

Louise was the last of six operas sung in San Francisco since 1988 by the late Jerry Hadley (1952–2007). Prior to Julien, the company had showcased Hadley’s artistry in portrayals of two other French heroes—Des Grieux and Hoffmann—as well as three longtime signature roles: Tom Rakewell, Tamino, and Nemorino.

Meaningful, crystal-clear text was always Hadley’s hallmark in any role, including Julien. As he vividly delivers that marvelous phrase, “le chant de victoire de notre amour triomphant” (“the song of the victory of our triumphant love”), the poet’s adoration of Louise becomes almost palpable. His ardent nature and natural high spirits register as strongly as his urgency when attempting to persuade Louise to run away with him. Of course, Julien’s devotion to his city indelibly colors the character. This proves especially memorable when the clarion-voiced Hadley—together with Fleming—sings ecstatically in unison, at the height of their Act III duet, “Paris! Paris! Cité de force et de lumière!” (“Paris! Paris! City of strength and light!”).

Louise’s mother is the least vocally demonstrative of the four key roles, but she’s formidable nonetheless, and unsympathetic for much of the opera. This character profits immeasurably from the multi-hued mezzo-soprano of Dame Felicity Palmer (see Palmer Q&A in the Rabbit Hole), previously hailed in San Francisco for La fille du régiment (1993) and Rusalka (1995). Palmer also gives an astonishingly detailed, line-by-line response to the French text, shaping it so authentically that one can scarcely believe the singer isn’t a native Frenchwoman. Charpentier has set the first words of the Act III intervention a cappella – “Je ne viens pas en ennemie” (“I haven’t come as an enemy”); here Palmer is extraordinarily intense, yet never once pushing for effect. When the mother admits how she and her husband felt when Louise left them, the sadness coloring “Elle était morte pour nous” (“She was dead to us”) communicates a heartrending finality.

Like Fleming, Hadley, and Palmer, Samuel Ramey was making a role debut. His portrayal of Louise’s father was something of a nod to San Francisco Opera’s history, if we remember that the legendary Ezio Pinza sang the role in the company’s first Louise. These two basses have often been compared, each possessing luxurious tone, flawless technique, and electrifying charisma. Prior to Louise, Ramey—who debuted as Colline in La bohème in 1978-79—had starred in San Francisco as the Hoffmann villains, Boris Godunov, and Attila.

As with the three other principals, Ramey’s distinctive timbre instantly attracts the listener’s attention. Charpentier doesn’t really allow the father to come fully into his own until Act IV, which he dominates throughout. While singing magnificently, Ramey also probes deeply in his lengthy aria, bringing affecting soulfulness to the lullaby-like passage the father sings to his beloved Louise. In the opera’s final ten minutes, with the vocal line turning much more baritonal, Ramey remains unfazed, as the father becomes increasingly enraged by his daughter’s defiance.

Louise includes too many supporting roles to name here, but among them are numerous vendors, an urchin, a streetsweeper, and a songwriter, as well as a debonair charmer written for lyric tenor and mysteriously identified as “A Noctambulist.” That character has previously lured away the daughter of the ragman. The latter role, meant for an especially full-toned bass, recalls that sad event in the still point of Act II’s first scene: a brooding, pained lament, movingly sung in 1999 by Kevin Langan.

Of all the episodes focused on supporting roles, especially exhilarating is the seamstresses’ workshop (Act II, Scene 3), where Louise’s eight colleagues chatter and gossip. Musically speaking, the heart of the scene belongs to Irma, one of opera’s most rewarding cameo roles for soprano. A truly blooming lyric voice is needed, one that can convincingly describe Paris as “the voice of pleasure and love” in her soaringly romantic ariette. Donita Vokwijn sings it radiantly in the San Francisco performance.

With so many other small but telling roles, major companies presenting Louise have always cast it in depth. San Francisco Opera certainly took this to heart in 1999—for example, by inviting a prominent leggero tenor from Belgium, Marc Laho, to make his U.S. operatic debut as the King of Fools in Act III. In addition to Langan and Volkwijn, among the other exceptionally gifted American artists here who went on to impressive careers were mezzos Catherine Cook and Judith Christin, tenors Jay Hunter Morris and Norman Shankle, and baritones James Westman and John Fanning.

Morris, who sang the Noctambulist, remembers “[director] Lotfi Mansouri had me on a small platform, like a soapbox, and I remember being so nervous that I’d fall off.” The costume was “tails, cape, cane, top hat, and, I think, a fake mustache, like a carnival barker.” The tenor felt “terrified and intimidated” working with the starry leading quartet, but gratified to be onstage with Hadley, one of his most important mentors. “I also hadn’t sung much in French. [Conductor] Patrick Summers is a strict taskmaster, and when you’re the rookie, you’re also often the whipping boy, so I had to work very hard. Lotfi was my champion, and he was always so full of joy.”

The performance is anchored throughout by Summers, at the time just beginning his first season as the Company’s principal guest conductor. Louise, his sixteenth San Francisco Opera production, was also his fourth in French, following Faust, Carmen, and Guillaume Tell. He captures Charpentier’s elusive conversational style—especially in the “local color” vignettes—as persuasively as the most musically grandiose climaxes. In Act III, the gathering of Montmartre’s denizens to crown Louise as “Muse of the Sacred Hill” offers an irresistible exuberance perfectly fitting this raucous scene. Then, in the final act, as Louise and her father reach peaks of anger and resentment, Summers draws genuinely hair-raising playing from his orchestra, totally attuned to the scalding final confrontation between the father and daughter.

Streaming San Francisco Opera’s Louise broadcast will surely delight everyone who loves French opera. If you were in the theater in 1999, savor this chance to relive the glories of that performance. And if Louise is new to you, prepare yourself for enchantment, Parisian style. Amusez-vous bien!

******

Singing Louise: A CLOSER LOOK

When she starred at San Francisco Opera as Charpentier’s Louise, Renée Fleming was already a greatly acclaimed artist with the company. Beginning in 1990, she’d triumphed in Le nozze di Figaro, Hérodiade, The Dangerous Liaisons (world premiere), Rusalka, and A Streetcar Named Desire (world premiere).

When I spoke with Fleming about Louise in the spring of 2022, she recalled finding the role (which, to date, she has performed only in San Francisco) heavier than other French heroines she’d sung previously: Gounod’s Marguerite and Massenet’s Salomé (Hérodiade), Manon, and Thaïs. “Louise is long, it’s more dramatic, the orchestration is bigger, and the opera’s final scene is very intense,” commented the soprano. Fleming also remembered, with some amusement, the dinner shared by Louise and her parents in the last act of San Francisco Opera’s production: “A restaurant was found that could create exactly the right dish—a cassoulet [stew with meat, pork skins, and white beans]. Cassoulet isn’t the best meal if you want to fit into your costumes!”

Singing “Depuis le jour” onstage in context for the first time delighted Fleming (“Being in Montmartre, looking down on the city of Paris is quite romantic”). In Charpentier’s working-class heroine she found an appeal in the role similar to that of Puccini’s Mimì, another seamstress trying to survive. “At that time, there was this fascination and romance about the lower socio-economic strata—the ‘starving artist.’ Look at the paintings of the period, with so many milliners and women working in dress shops. Louise was also a young woman, so she didn’t have autonomy—not enough of a say in the choices that others were trying to make for her.”

Fleming cherished her Louise colleagues. She’d already been thrilled by Samuel Ramey, with whom she’d collaborated at other companies in Faust and Le nozze di Figaro. She was riveted by the stage presence of Felicity Palmer, and by the mezzo’s eloquent way with the French text. The soprano loved working with Jerry Hadley, whom she’d admired ever since hearing his Tom Rakewell years before: “What he could do with his voice—the refinement, the risk-taking—was spectacular. That was why he became a star.” Fleming remembers Lotfi Mansouri as a truly collaborative director, and conductor Patrick Summers (with whom Fleming developed a close, ongoing association), she found “smart, incredibly erudite, with tremendous historical knowledge of repertoire in general—really a pleasure.”

The fact that Louise turns up so rarely isn’t lost on Fleming. She confesses to disappointment that the repertoire is shrinking, “because people who love opera do want to hear other things, not just the top ten!”

Roger Pines, who recently concluded a 23-year tenure as dramaturg of Lyric Opera of Chicago, is a contributing writer to Opera News, Opera (U.K.), and programs of opera companies and recordings internationally. He has been on the faculty of Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music for the past three years.