Backstage with Matthew:

Text as Design: The Visual Narrative of Omar

With the words “I am Omar,” Omar ibn Said reclaims the narrative of his life, stolen from him in 1807 when he was enslaved and brought from what is now Senegal to South Carolina. His autobiography, written in 1831 is one of 42 documents written by Omar in Arabic and English, now housed at the Library of Congress, and it forms the impetus for the Pulitzer-winning opera by Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels on our stage this November.

Fatima, Omar’s Mother, as played by Taylor Raven. Photo: Cory Weaver

Fatima, Omar’s Mother, as played by Taylor Raven. Photo: Cory Weaver

The centrality of text to Omar reflects the schism of his life. He was a highly-educated scholar who spent twenty-five years studying in an Islamic seminary in West Africa, and at age 37, was suddenly denied his freedom, his religion, his scholarship and his voice. He was eventually permitted to write, but decades of mis-translations and appropriations of his writings continued to deny Omar his story. It is only now that scholarship and this opera are reconnecting us to the deep resonance of Omar’s texts.

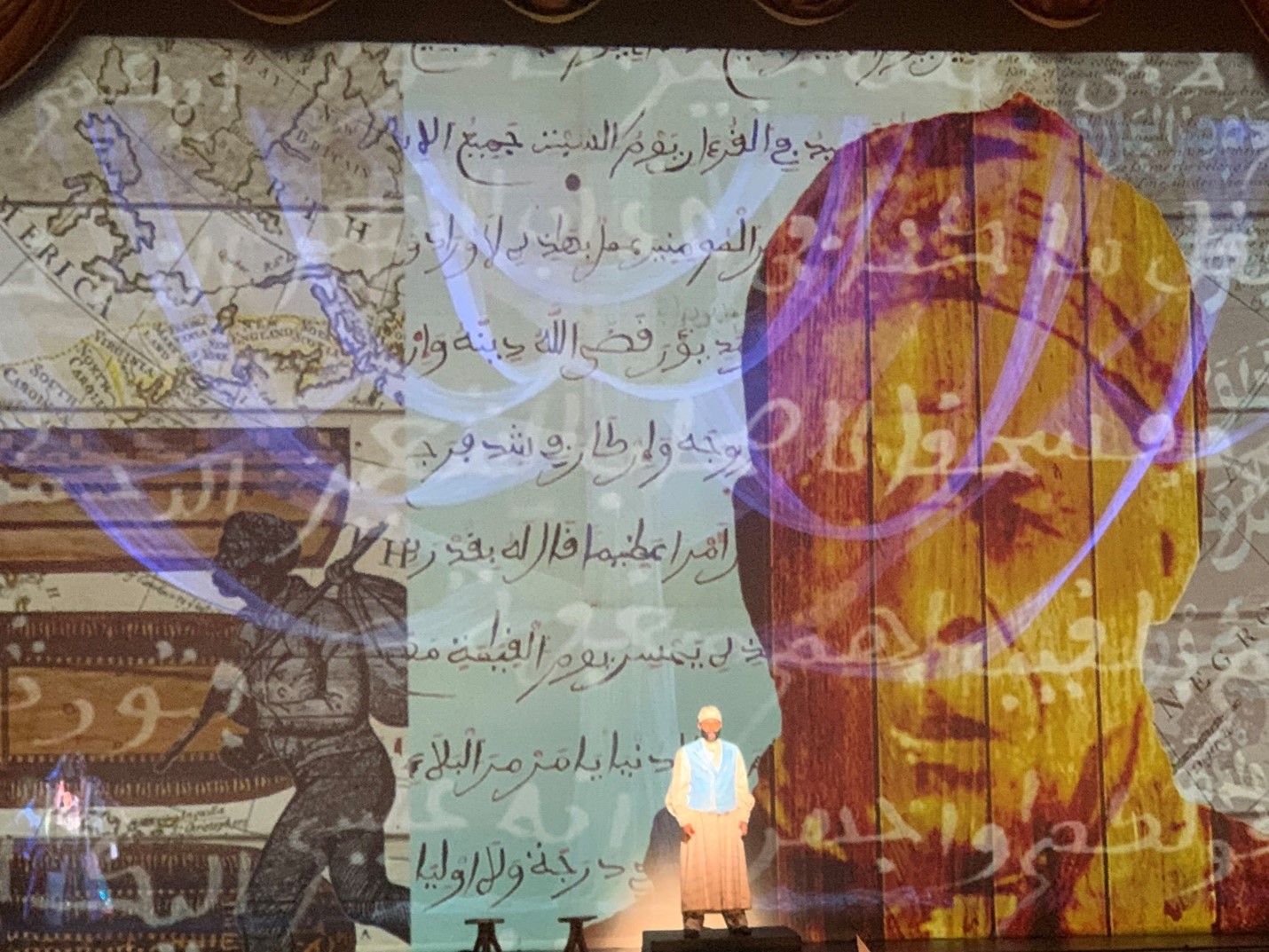

The opening of Act II of Omar. Photo: Cory Weaver

The opening of Act II of Omar. Photo: Cory Weaver

The opera—an artistic response to the text rather than a historical accounting of Omar’s life—represents the integration of many layers of language: of musical languages, spoken languages, written languages, visual languages. Composers Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels weave a rich tapestry of musical idioms—from West African kora, bluegrass, spirituals, folk music and jazz—with a beautiful emotive synthesis. That synthesis of language also becomes the foundation for the visual design, with sets and costumes serving as a canvas for the intersection of many worlds as we’ll see below.

For production designer Christopher Myers, this intersectionality of languages becomes a powerful expression of the hyphen in “African-American”—the intersection point that binds cultures in a much bigger conception of humanity. Omar’s voice intersects with others’ voices, and through this visual intersection the complex institution of slavery onstage is created.

The intersection of different texts from the closing scene of Omar.

The intersection of different texts from the closing scene of Omar.

In projections (designed by Joshua Higgison) , on scenery (designed by Amy Rubin) and on costumes, we see Omar’s written word in a number of forms—in Maghrebi Arabic (a west African form), in English, and in his own drawings. We also see the hand of another enslaved Islamic scholar, Sheikh Sana See. You can see examples of these writings in Omar’s costumes below:

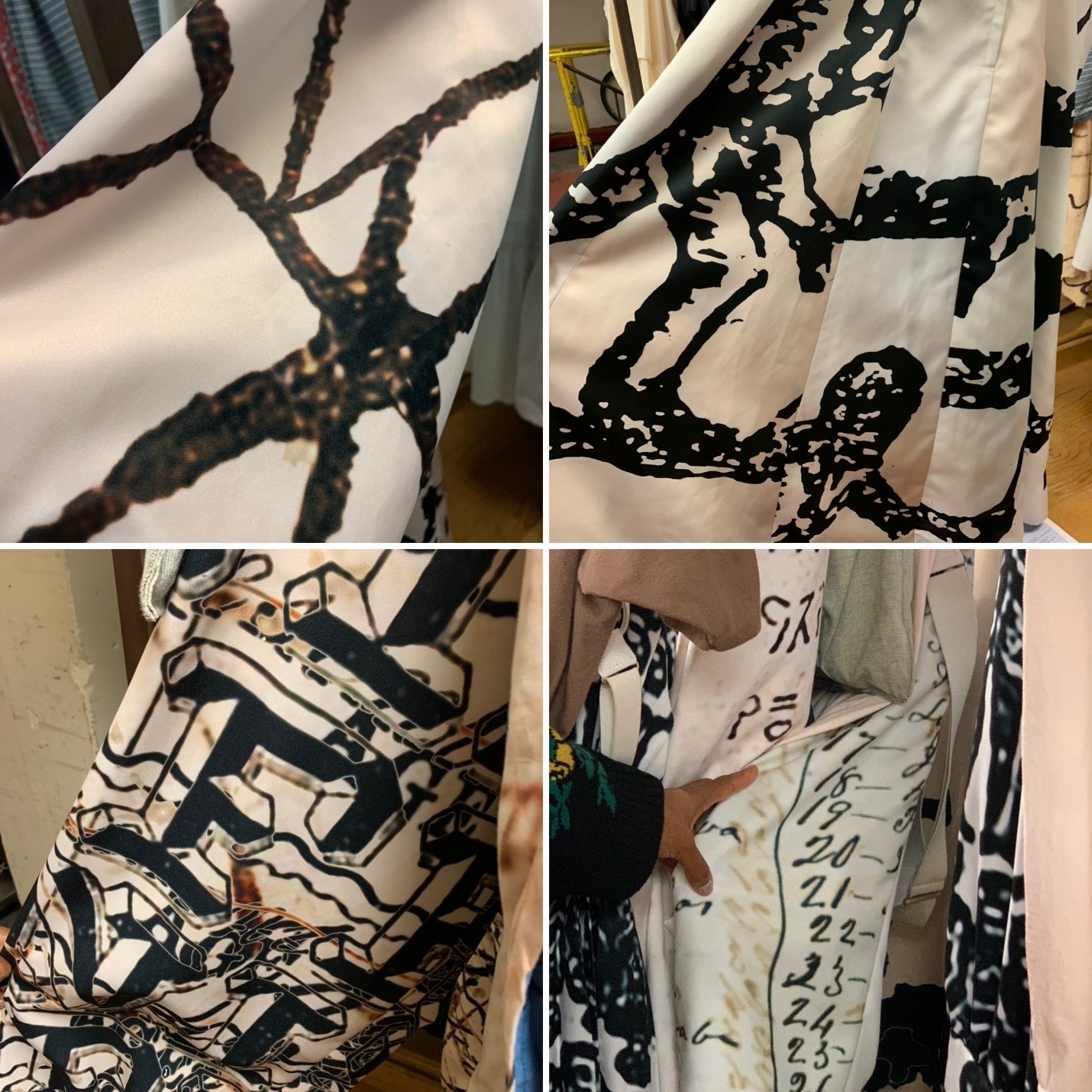

A selection of Omar’s costumes, including script in his hand (right and middle)

A selection of Omar’s costumes, including script in his hand (right and middle)

The costumes, designed by April Hickman and Micheline Russell-Brown, give deeply meaningful individuality and identity to the characters. It was important to Kaneza and her designers that the visual world of Omar transcend the stereotype costumes of slavery rags. Rather, they have crafted beautifully individuated costumes with shapes, designs, fabrics and colors that hold historic information and that connect both past and future. The authenticity of text is married with more contemporary forms and designs. Below, for example, are costumes from the Middle Passage scene—the impossibly harsh journey of enslaved prisoners across the Atlantic from Africa to the east coast of America. Each costume reflects a different West African language—Bamum (Cameroon/Nigeria), Vai (Liberia/Sierra Leone) and Ngwe (Cameroon)—a visual manifestation of the inability of those making this horrific journey to be able to communicate with each other—communities and societies ripped apart with no knowledge of where they were going or even to talk about it with each other.

Costume pieces from the Middle Passage scene incorporating a variety of West African languages

Costume pieces from the Middle Passage scene incorporating a variety of West African languages

As you see in these images, many of the enslaved characters’ costumes are in a color palette of parchment, of writing. This contrasts with the vibrancy and immediacy of the colors of the costumes of West Africa that we see at the beginning, poignantly carried through into the Carolinas by Omar’s Taqiyah (prayer cap) with which he is ultimately reunited thanks to the kindness of a fellow enslaved woman, Julie.

Omar (Jamez McCorkle) and Julie (Brittany Renee). Photo: Cory Weaver

Omar (Jamez McCorkle) and Julie (Brittany Renee). Photo: Cory Weaver

And then, as mentioned earlier, the visual designs also connect us through many different texts to the infrastructure of slavery, with costumes that incorporate imagery from (clockwise below):

- the ‘signature’ marks made by illiterate slave owners on contracts purchasing slaves;

- a block print used in a runaway ad for escaped slaves

- a ship’s manifest from the Middle Passage

- an insurance document (insurance companies wrote policies to insure slave owners from the loss or death of enslaved people)

Costumes incorporating a variety of imagery and text from the infrastructure of slavery

Costumes incorporating a variety of imagery and text from the infrastructure of slavery

This extraordinary integration of design into each individual costume underpins an important aspect of Omar and, more generally, of the role of theater for Kaneza. For Kaneza, the theater is a place to dream, to envision, to understand things bigger than ourselves. The theater is the temple of myth and a place where we can hold the contradictions of the world of which we are a part. It is so important to Kaneza that Black narratives not simply be historical expressions of reality, told on the theatrical or operatic stage; rather they must embody myth and meaning, hope and dreams.

Director Kaneza Schaal with one of Omar’s mother’s costumes

Director Kaneza Schaal with one of Omar’s mother’s costumes

That idea of envisioning, of reaching into the consciousness of humanity, is such an important part of Omar. It is particularly felt in the incredible shift in Act II as the opera moves into a sequence of profound affirmations. Omar’s voice is expressed through the beauty of his writings, not just as a conduit with which to understand a period of history. It’s a sublime ending, both musically as Rhiannon and Michael embrace the full architecture of the temple of art that is our theater, and visually as the set becomes a huge enveloping tree. The tree is such an important visual that Rhiannon calls it out in the libretto. It becomes a pillar for how we hold the intersection of religion, of language, of culture, a place where Omar can find spirituality, of family, of place. For Kaneza, the tree is a symbol which invites each of us to connect with our own narrative, and to which we bring our own lexicon of experiences.

Omar (Jamez McCorkle) in front of the Act II tree

Omar (Jamez McCorkle) in front of the Act II tree

The depth of meaning that is embedded in the music and the design of Omar connects us emotionally and spiritually to a man who wrote his autobiography almost two hundred years ago in a world where the individuality of humanity was all-too-often brutally excised. Through the musical lineage that Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels bring to Omar (you can read more about this in my backpage article in the program book), and through the deep honoring of text in the production design, Omar ibn Said invites us all to connect across time and place.

Photo: Cory Weaver

Photo: Cory Weaver