Sun Wukong, the Pop Culture Chameleon

There are trickster gods, and then there’s Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, who makes Loge, the Norse God of mischief in Wagner’s Das Rheingold (a.k.a. Loki, in the Marvel Comics Universe) look like a rank amateur. Born from a magic rock and armed with a staff that can grow to skyscraper height or shrink behind his ear, Wukong is always one temper tantrum away from fighting the celestial bureaucrats, making him mythology’s ultimate multitasker.

Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West gave us a monkey with personality: rebellious, funny, and surprisingly relatable for someone who once fought an entire Heavenly army with only a stick. But the novel wasn’t the final word: Since its publication in 1592, Sun Wukong has leapt into Chinese opera—Peking opera, among other regional styles—to become a stage sensation. Ming- and Qing-dynasty audiences loved watching acrobatic actors in golden headbands leap around like Spider-Man (but with more backflips) while hurling quips at both friend and demonic foe. By the late 19th century, the Monkey King had become one of the most beloved figures in the stage repertory, often entertaining crowds in temples and festivals. Some stage versions highlighted his clown-like mischief, others like Jin Qian Bao (“Gold Coin Leopard”) showcased his loyalty and heroism. The Monkey King was already practicing what pop culture would later perfect: reinvention.

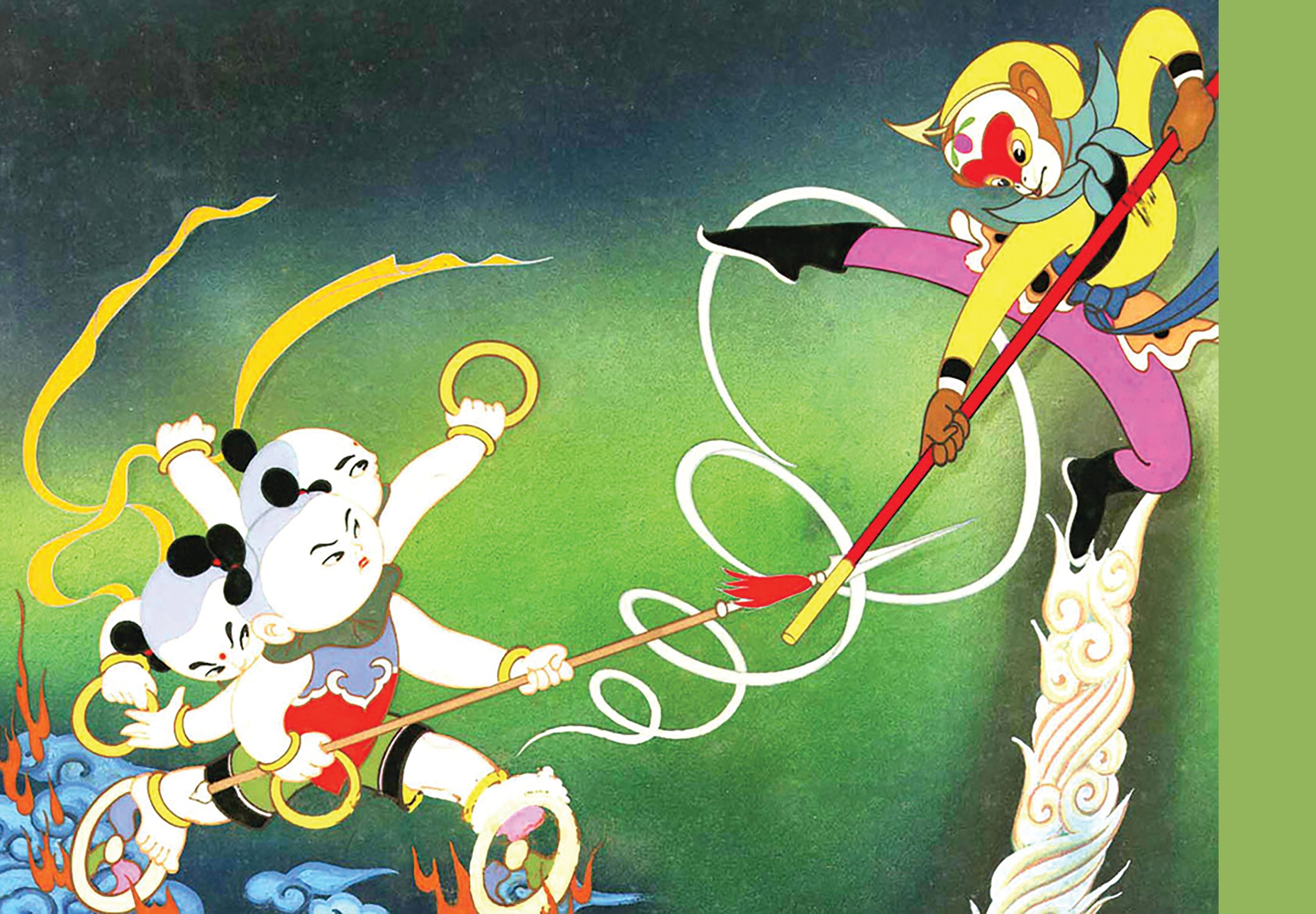

Fast forward to the 20th century and China’s first animated feature film, Princess Iron Fan (1941), when producers Wan Guchan and Wan Laiming gave audiences a taste of a new kind of Wukong. Created during the second Sino-Japanese War, the film wasn’t just entertainment but also symbolic defiance, a cheeky monkey resisting demons and overcoming impossible odds. The Wan brothers’ 1965 color follow-up Havoc in Heaven sparkled even more with acrobatic fights and a rousing score—a masterpiece of Chinese animation that visually cemented Sun Wukong as a pop icon.

By the 1960s and ’70s, Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers Studio (the “Oriental Hollywood”) was churning out martial arts epics on an assembly line. Naturally, they couldn’t resist the Monkey King. Director Ho Meng-Hua made not one but four Journey to the West films between 1966 and 1968, each blending martial arts action with low-budget charm. Then there’s legendary director Chang Cheh’s Fantastic Magic Baby (1975), a filmed version of a staged theatre-like rendition of Sun Wukong’s famous battle with the Red Boy. It’s worth seeking out for what follows the end credits: a 36-minute film condensing two staged Peking opera performances.

Meanwhile in Japan, the Monkey King story inspired the 1970s cult TV series Saiyūki (released in English-speaking countries as Monkey), with Sun Wukong reimagined with campy humor and a rock-inspired soundtrack, reflecting both a countercultural vibe and the current Japanese TV aesthetics. Naturally, anime also wanted a piece of the Monkey King pie. First, there was Toei’s 73-episode series Sci-Fi West Saga Starzinger (1978–79), known in the US as Spacekeeters, transplanting Journey to the West into space, with Wukong a hot-headed cyborg who along with Princess of the Moon and her two other robot companions must restore the Galaxy Energy in the year 2072. Then came Dragon Ball Z (1989) and its numerous spinoffs, introducing anime to an entire generation of kids worldwide. With its hero Son Goku being literally Sun Wukong’s Japanese moniker, Dragon Ball Z officially took the character global.

Back in Hong Kong, Sun Wukong continues to be ever-present in both TV and film, albeit initially done in a more traditional fashion. Ten years after China’s CCTV produced its 1986 TV series, re-establishing the national icon as a small-screen superstar, Hong Kong’s TVB made two Monkey King series (1996–98). A major turning point, however, came when comedian-director Stephen Chow’s two-part Chinese Odyssey (1995) reimagined the quest for the sutras as a time-travel romance, complete with Chow’s trademark mo lei tau (“makes no sense”) verbal slapstick. These two films became cult classics across Asia, proving that Wukong could work just as well in parody as in earnest heroics and unrequited love. But Chow wasn’t done: In the 2010s, he directed Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) and co-directed its sequel Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) with celebrated Hong Kong cinema wizard Tsui Hark. These big-budget, effects-heavy fantasy adventures were somewhat darker, though still sprinkled with Chow’s irreverent humor.

By the early 2000s, Hollywood decided it wanted in, with the NBC-produced Monkey King (2001), also known as The Lost Empire, marking that character’s official entry in America. Then came The Forbidden Kingdom (2008). Though not strictly a Journey to the West adaptation, the film starred Jackie Chan and Jet Li (the latter playing a variation of the Monkey King), mostly existing to give martial arts fans the Chan-Li martial-arts crossover they’d yearned for. While back in China, Hong Kong director Soi Cheang, who revitalized modern martial-arts cinema in Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In (2024), delivered a blockbuster Journey to the West trilogy (2014–18) with Wukong played by Donnie Yen in the first film and triple-threat singer/dancer/actor Aaron Kwok in the two sequels. Filled with sweeping digital landscapes and gigantic Kaiju-like monsters, Cheang’s films portrayed the Monkey King as a caped-crusader-caliber superhero. Embracing style over substance, Asia audiences devoured these films like celestial peaches.

American cartoonist Gene Luen Yang brought Sun Wukong into the comic book idiom with his 2006 award-winning graphic novel, American Born Chinese, with the Monkey King becoming a metaphor for Asian American identity, grappling with questions of assimilation, self-acceptance, and cultural pride. Witty and heartfelt, it made clear that Wukong’s story isn’t just universal but also adaptable to the personal and political struggles of diaspora communities. Then in 2023, Disney+ released a live-action series adaptation, strutting Wukong into a contemporary teen drama complete with martial arts and dazzling visual effects.

Artwork for Black Myth: Wukong

Artwork for Black Myth: Wukong

Xinhua/Alamy

In the digital age of the 21st century, Wukong has also found a natural home in video games, where his agility, combat skills, and magical abilities translate seamlessly into gameplay mechanics. Whether it’s League of Legends, Smite, Fortnite, or the Chinese action role-playing game Black Myth: Wukong, Sun Wukong continues to provide a canvas for reinterpretation.

So, why do we keep going bananas (pun intended) for the Monkey King? First, he’s infinitely adaptable. Trickster, warrior, sage, comic relief—he is all of them. Need a moral allegory? He’s there. Need a superhero? He’s already got the staff. Second, he’s relatable. As a magical monkey who once punched the Celestial Emperor in the face, Wukong embodies the full range of human contradictions: rebellious yet loyal, arrogant yet vulnerable, divine yet mischievously human. He is like us on our worst and best days, only furrier. Contradictions like these allow pop culture to reimagine him over and over again.

Finally, he’s fun. Journey to the West might be packed with Buddhist allegory, but Sun Wukong brings chaos to order, comedy to morality, and mischief to mythology. Which is why the Monkey King is so enduring: no character better symbolizes the adaptability of myth in pop culture. Equally at home on stage, in space, in comics, or in CGI-laden blockbusters, Wukong is the perfect icon for pop culture’s ever-changing tastes and technologies. He reminds us that myths aren’t dusty relics but rather living stories, ready to transfigure into whatever form we need. Whether he’s wowing audiences on a big screen—sometimes in stunning 3D—or letting gamers swing his staff in 4K resolution, the Monkey King never stops reinventing himself. And that, perhaps, is his greatest magic trick of all: never going out of style.

Four centuries after Wu Cheng’en tucked him into his novel, Sun Wukong has leapt beyond the written page and somersaulted across all media. Wukong doesn’t just survive new media revolutions—he thrives in them. To borrow his own party trick, he can clone himself into 72 different forms, and pop culture has willingly embraced his transformation, granting the simian diva (well, he did disguise himself as a woman to fight the White Bone Spirit) his multiple detours. And—spoiler alert!—he has no plans to slow down.

Frank Djeng ( 鄭曉霖) is a Hong Kong Cinema historian who has recorded hundreds of audio commentaries for Blu-rays of Hong Kong films from prestigious labels such as Criterion, Arrow, Eureka, and 88 Films. He is also a lifelong opera enthusiast, a passion first sparked at age 11 when he heard Georg Solti’s recording of Parsifal.