Episode in the Life of an Artist

Ask what opera is all about, and La Bohème is likely to be part of the answer. Its beauties inspire love in first-timers and devotees. But Bohème is about more than beauty. It demonstrates what opera can do.

Ask what opera is all about, and La Bohème is likely to be part of the answer. Its beauties inspire love in first-timers and devotees. But Bohème is about more than beauty. It demonstrates what opera can do.

One thing opera can do is render time more convincingly than any other method of storytelling. La Bohème is an artist’s self-portrait, an account of himself as a young man. That artist, Rodolfo, is the memory’s author, and in Bohème he reflects on who he was. Take note: The man telling his story is different from the man we see on stage. We get to know the onstage Rodolfo through the words we hear him utter. We get to know the older Rodolfo through the music, the medium that carries the words, the medium that delivers the recollection. In a written memoir, the author comments self-consciously on episodes of his past. Opera dispenses with such narrative clumsiness. It can render past and present simultaneously, mimicking life. It mirrors what we do when we recall parts of our own past and reflect on what they meant, and on what they continue to mean at the moment we recapture them. No other kind of narrative achieves this so elegantly.

Now trade my abstractions for the action on stage. Puccini aligns us with his protagonist before we know what is happening. A minute in, we encounter Rodolfo’s theme, fifteen bars that over the next two hours we will hear in various forms. Here, with its first appearance, the composer dresses the most mundane of subjects in his most arresting music. “In the gray skies I’m watching the smoke from a thousand Paris chimneys,” Rodolfo sings in a breezy seven bars.

Then comes something more unsettling, a phrase shaped symmetrically and sung B/A/A/D/A/A/G, the repeated As rising and falling a fourth, pivoting around the D before the final A drops a step, as did the first interval of this phrase, this phrase that evokes such a powerful sense of nostalgia before the music recovers and Rodolfo ends in a rising flourish. What we hear in the music itself is something generous and carefree, tinged at midpoint with a hint of melancholy. What we hear Rodolfo tell us is that he is thinking about all those comfortable warm houses while the old stove in the garret sits idle, mounting no defense against the December cold. In fitting sounds so sublime to words so banal, Puccini offers a musical equivalent to our tendency to embellish the past. Times were hard back then, but those were the days.

Think of La Bohème as narrated by an older-and-wiser Rodolfo who recalls his twenties, when he was a wannabe writer, cold and hungry in the loft he shared with three artsy friends: a painter, a philosopher, and a musician. Times were hard back then, but those were the days. Into this scene of poverty walks Mimì, appearing almost as an apparition. The slow sunrise of a crescendo in the strings presages her aria “Mi chiamano Mimì”: “I’m always called Mimì.” Her name is actually Lucia, a fact she discloses just once and never repeats. Lucia: light. Light is what she offers Rodolfo, in the form of love and acceptance such as any poet craves from his audience. Mimì is his audience now, and she will be forever after, because everything he does and writes he will do and write for her. Now he leaves behind the goofy horseplay of the opening scenes, the banter with the guys. He gets serious. He performs for Mimì. Who am I? I’m a poet. How do I live? Yeah, well—I live. In an instant, Mimì is in love. Rodolfo has the lines and knows how to use them. Yet his delivery is anything but slick. He hears himself pleading his case to Mimì in a new voice, honest and unguarded. Mimì is not his first girlfriend—his approach to her is too eloquent for a novice—but she is the one who will make the difference, the one who has made the difference, as the older-and-wiser Rodolfo/narrator understands. Mimì, as Rodolfo recalls her, will always illuminate the memory of those rough days, in which she played so central a role, those days that, for all their hardship, will always bear the tender ache suggested in that pivotal rising and falling fourth.

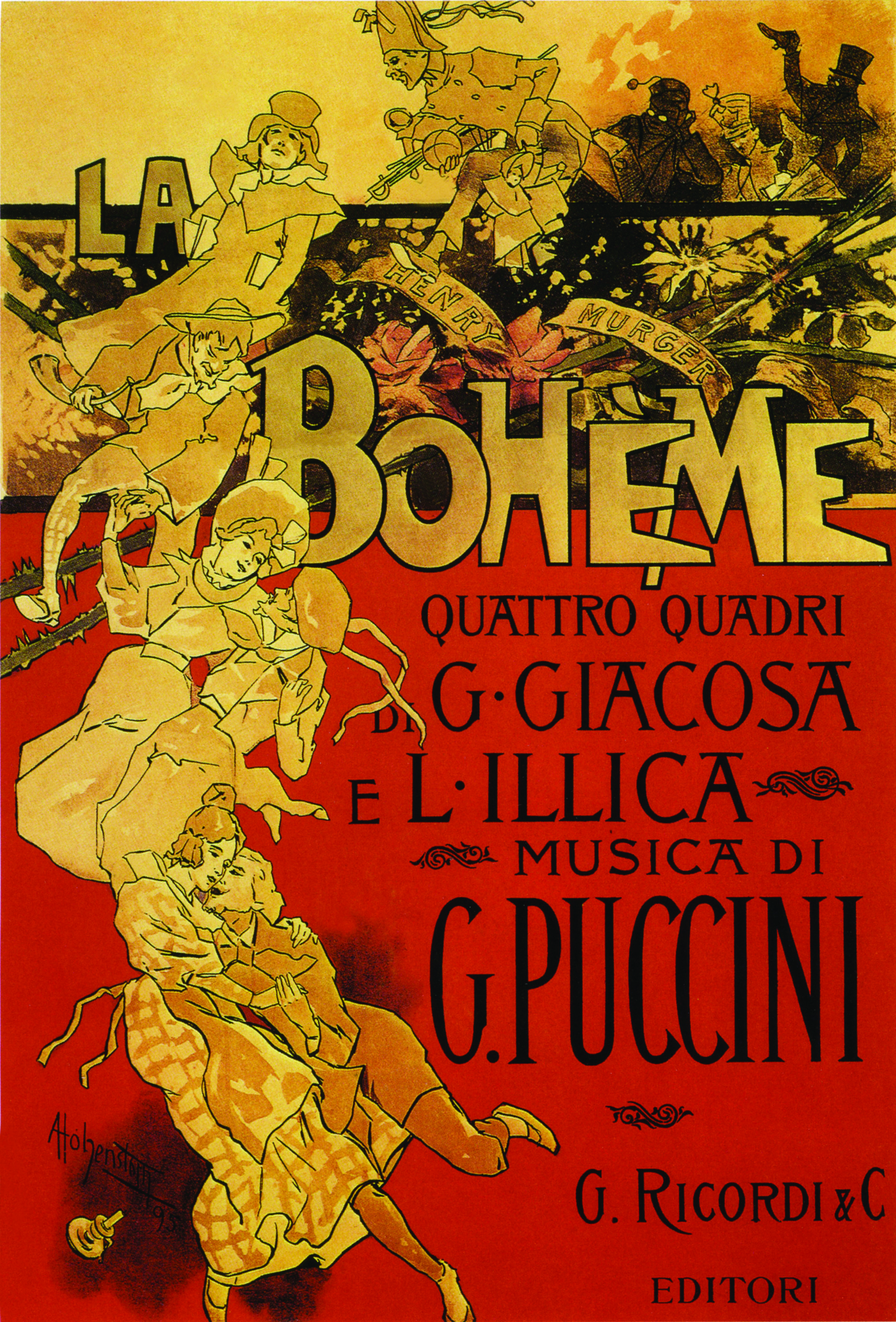

I have focused on one moment in this two-hour opera. That moment launches the drama’s trajectory in an uninterrupted arch. Puccini’s fusion of action and music is surely one reason his Bohème so completely overshadows Leoncavallo’s. Ruggero Leoncavallo, remembered today only for Pagliacci, the first of his many operas and operettas, was at work on his own Bohème when he learned his rival was also adapting Scenes from Bohemian Life, an 1849 collection of sketches by French writer Henri Murger. Although Puccini in 1895 had produced only one bona fide success of his own, that success was Manon Lescaut. Leoncavallo, finding himself pitted against a composer who could create an opera of such sweeping melodies and impact, understood what he was up against, and he reacted badly. After all, he had discovered Murger first. Puccini stayed cool. Let the public decide, he said, with the confidence of an artist who knows he is good for more than one hit. The two Bohèmes co-existed for ten years, until Leoncavallo’s vanished from the stage and Puccini’s went on to become the world’s most popular opera.

Anyone inclined to sit through Leoncavallo’s Bohème will understand why time has favored Puccini, who achieved such different results using similar material. Leoncavallo’s opera, an ungainly hybrid that starts as flaccid comedy, then shifts to blustering tragedy, feels pieced together and fails to deliver the urgent sense of life that is Puccini’s strong suit. Leoncavallo believed himself a competent librettist and fashioned his own script. In librettists Giuseppe Giocosa and Luigi Illica, Puccini found the ideal collaborators, both of them accomplished writers who had worked with him on Manon Lescaut and who after Bohème would deliver the librettos for Tosca (1900) and Madama Butterfly (1904). Using Murger’s collection of stories drawn from his own experience as a struggling writer, they devised a tale marked by the realism and naturalism audiences would have found in contemporary novels. Puccini, who knew what made a script live or limp, demanded rewrite after rewrite, forcing his librettists to ask themselves more than once if working with this man was worth the anguish.

The results in Bohème speak for themselves: words that inspire the ideal musical setting and that dictate the pace. Consider the two parts of Act I. The first part rushes, pedal-to-the-floor as the garret-partners trade jokes and jibes. This contrasts with the act’s second half, when Rodolfo and Mimì discover each other and the music slows to a rhapsody, embodying a passion that supplants kid stuff with ecstasy.

Early audiences faulted Bohème for what we now regard as one of its great strengths, its realism. So downbeat a story set against so gritty a background, those characters you might encounter on any city sidewalk—all that was fine for the pages of Balzac or Zola or Dickens or Frank Norris, but the opera stage was reserved for more graceful material. (Audiences had not yet encountered Richard Strauss’ Salome.) Often opera asks us to suspend our disbelief. Not Bohème. We recognize its world.

Yet La Bohème is hardly a documentary. Puccini writes melodies so seductive, and he is so easy to love, that he is often dismissed as an entertainer, as if that vocation left no room for artistry. Bohème should convince us otherwise.

Any catalog of Puccini’s gifts has to include his extraordinary use of the orchestra. In the great aria “Che gelida manina,” for example, he is elegant and reserved, applying a brushstroke of strings and a dab of winds and harp to color the moment Rodolfo grasps that he is in love. His theme—the one we heard a minute in—has already returned, first on solo violin, with a delicacy that suggests his vulnerability, and again in just a hint as he stands transfixed by Mimì, stunned by the luck that has led her to his door. Now, in prelude to his greatest aria, his theme turns gentle and broad—a setting for serious words—and even as it transforms into “Talor del mio forziere,” Puccini holds the orchestra back, allowing his singer full rein in this impossibly romantic music. In his orchestral restraint, even more than his fortissimos, Puccini displays his artistry.

The orchestra leads us through the drama. Act I opens with a rush of strings, winds, and brass as Rodolfo and Marcello kvetch and joke. It closes with a gentle reprise of “Talor del mio forziere,” growing to a great crescendo as Rodolfo and Mimì pledge themselves to each other, and at last closing quietly, the lovers’ voices receding offstage. Act II, perfectly shaped, ends as it began, with the Christmas revelers. In between, we meet Musetta. Her waltz is a masterful feat of foreplay and consummation, teasing and swelling until it climaxes fortissimo and tutta forza, to be followed by a quiet denouement before the revelers return. Act III, opening and closing with a great snap to attention in the orchestra, concludes as Act I ended, only now Rodolfo and Mimì sing of parting, not of the shared life that awaits them, and the last music we hear is a sad variant of “Talor del mio forziere.” Act IV’s structure follows that of Act I: orchestral bluster, upbeat mood, then reversal, as Musetta enters with the news that Mimì hasn’t long to live. A telling reference to Rodolfo’s theme, for the first and only time heard in the minor mode, underscores the tragedy. As Mimì dies, we recall the lovers’ meeting in a fleeting pianissimo reference to “Che gelida manina.” Mimì promised springtime in her first aria, and flowers, a return to life. Rising flutters in the flute accompanied her words then, and they recur as Musetta mourns the doomed Mimì.

Although the flowers Mimì fashions from bits of fabric will last, nothing that lives and breathes can run out the clock. Real flowers die and youth passes. What Mimì and Rodolfo shared was an episode, destined to end—even if its memory will endure as surely as Mimì’s flowers. In La Bohème, Rodolfo has seen to that.

Larry Rothe’s books include For the Love of Music and Music for a City, Music for the World. Visit larryrothe.com.