Mozart Comes of Age

According to his widow, Constanze, Mozart experienced the happiest period of his life while immersed in Idomeneo in the winter of 1780–81, when he was temporarily living in Munich to complete the score. Constanze and Mozart did not wed until 1782—after he had settled in Vienna—so the memories he later shared of working on the opera must have left a particularly vivid imprint.

According to his widow, Constanze, Mozart experienced the happiest period of his life while immersed in Idomeneo in the winter of 1780–81, when he was temporarily living in Munich to complete the score. Constanze and Mozart did not wed until 1782—after he had settled in Vienna—so the memories he later shared of working on the opera must have left a particularly vivid imprint.

Years later, during a visit to Salzburg to visit Mozart’s father, Leopold, and sister Nannerl, Constanze directly witnessed the emotional power Idomeneo still held for him. The four sat around the keyboard to perform the Act III quartet in an informal rendition—Leopold and Wolfgang as the father and son (Idomeneo and Idamante), Constanze as Ilia, and Nannerl in the dramatically fiery role of Elettra. Mozart, overcome by the music and memories, burst into tears and had to leave the room. “It was a while before I could console him,” Constanze recalled.

Happiness and heartbreak—it should come as no surprise that Idomeneo aroused such emotional polarities, for Mozart invested his deepest creative self in the opera. This was not just another commission but a deeply personal investment, a crucible for Mozart’s evolving sense of self as a man and as an artist. Idomeneo’s emotional charge remains potent to this day, even if modern audiences were slow to recognize the opera’s extraordinary qualities.

The term “breakthrough” genuinely applies to Idomeneo. For Mozart, the commission arrived at a precarious moment. After years of touring and seeking permanent employment, he was stuck in the stifling confines of Salzburg, frustrated by the humiliations of working for the Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo, who employed both Mozart and his father. The young artist’s efforts to secure a meaningful position that corresponded with his ambitions had come up empty. A lengthy trip across Western Europe in 1777–78, with a sojourn in Paris, ended in disappointment and the sudden death of his mother. Mozart returned to Salzburg demoralized and cornered.

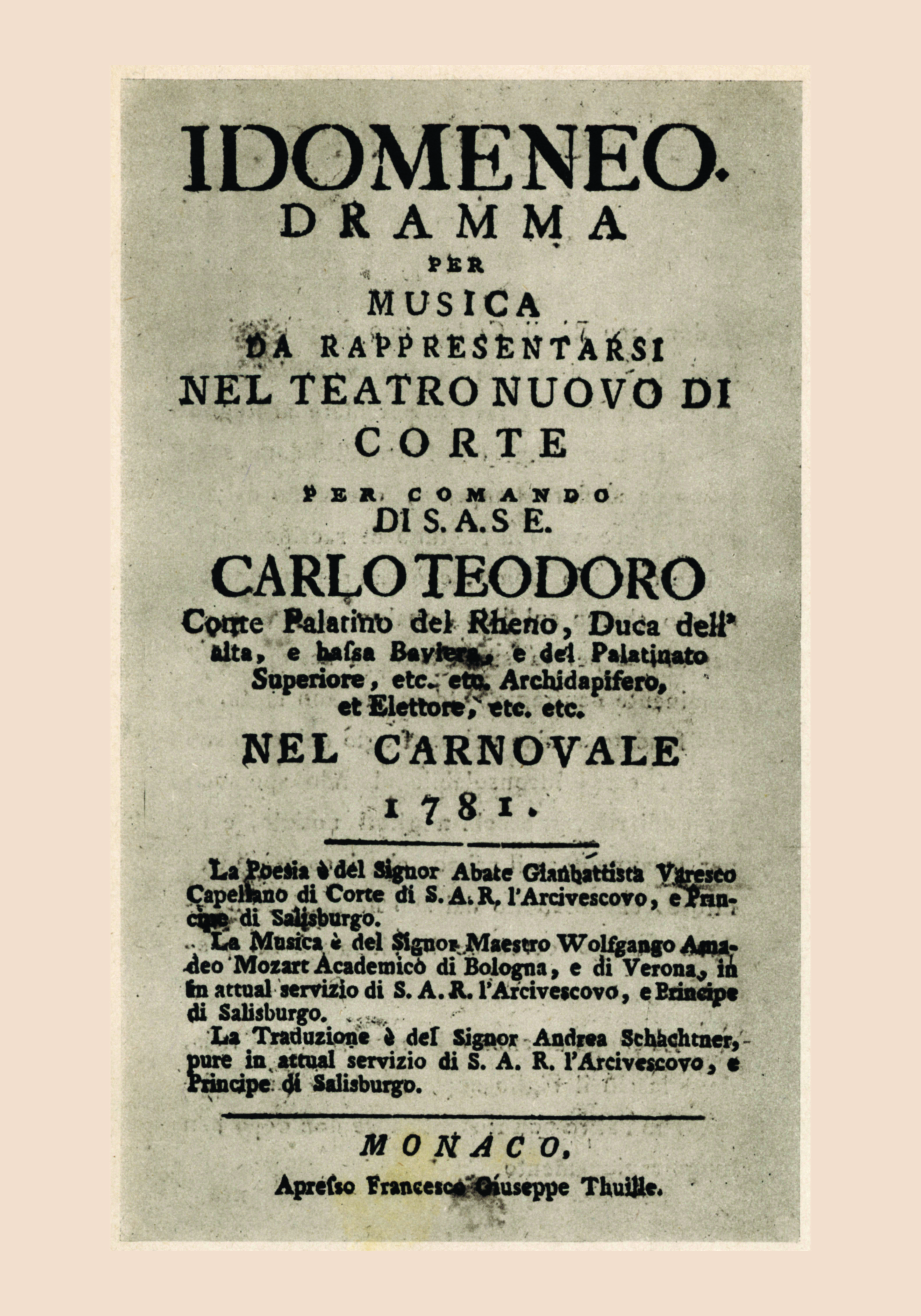

Yet the Paris sojourn brought new insights. There, Mozart encountered the reformist opera of Gluck and was introduced to the dramatic conciseness and expressive force that marked a new direction in the genre. His stay in Mannheim, meanwhile, proved artistically invigorating. Karl Theodor, the Elector of Bavaria—an enlightened monarch in the mold of Frederick the Great of Prussia—was especially inclined toward music and supported an orchestra then widely regarded as the finest in Europe. Mozart forged significant friendships in this milieu and absorbed the ensemble’s symphonic finesse. These connections paid off when Karl Theodor relocated his court to Munich and commissioned Mozart to write the new opera for the 1781 Carnival season.

The opportunity proved to be a lifeline. It offered Mozart a chance to escape Salzburg, to work in Munich with exceptional musicians and a professional company, and most importantly, to return to the genre he loved most: opera. The Idomeneo project also gave Mozart time away from the Archbishop Colloredo’s court. Though officially granted six weeks’ leave, he extended his stay to several months. Not long after the premiere in January 1781, he would sever ties with Colloredo and launch the final phase of his career as a freelance composer in Vienna.

Thanks to the detailed correspondence with his father, Leopold, who served as intermediary with the librettist Abbé Giambattista Varesco back in Salzburg, we gain a remarkable glimpse into Mozart’s creative process. The letters reveal an artist obsessed with dramatic integrity, pacing, and emotional truth. Mozart critiques the singers’ acting—one “stands around like a statue”—and trims Varesco’s florid text to sharpen its impact. Of the oracle scene near the end of the opera, he warns: “The longer it goes on, the more the audience will become aware that there’s nothing real about it. If the speech of the Ghost in Hamlet were not quite so long, it would be much more effective.” Later, as opening night approached, Mozart ruthlessly cut whole numbers—including some of the score’s most splendid moments—to shorten the running time.

Varesco had adapted his text from an earlier French libretto by Antoine Danchet, originally set by André Campra in 1712 as a tragédie-lyrique. The story fleshes out its mythic source with new invention. Idomeneo’s predicament—having returned from the Trojan War, he survives a shipwreck only to find himself bound by a vow to Neptune to sacrifice his son, Idamante—echoes the better-known human-sacrifice tragedy of Agamemnon and Iphigenia, as dramatized by Euripides. The libretto weaves into the drama another figure from the cursed House of Atreus: Agamememnon’s other daughter, Electra (Elettra), appearing here as a refugee from Mycenae. Though she does not have a part in the original myth of Idomeneo, her presence adds a charged layer of passion and destabilizing force.

Mozart’s treatment of the myth reflected both Baroque tradition and Enlightenment reform. He preserved the dramatic gravitas of the original but stripped away much of its elaborate divine machinery. Neptune remains the only god to intervene, and the opera replaces the tragic ending of the French source (in which Idamante is indeed sacrificed) with a resolution based on reason, compassion, and love—a triumph of Enlightenment ideals over superstition and the patterns of fate.

That theme—the struggle between obedience to authority and the courage to act with moral autonomy—echoes throughout the opera. It’s not only the literal father-son dynamic that plays out between Idomeneo and Idamante but also the larger symbolic confrontation between old and new orders.

Idamante, like Mozart, must find his own path. He is rejected by his beloved Ilia (initially), seeks his father’s approval, and ultimately faces the sea monster terrorizing Crete. His decision to confront the beast signals a turning point: an embrace of agency over submission. Idomeneo, by contrast, is a tragic figure caught in the coils of an ancient vow. Though he pities his son, he clings to a code of honor that no longer fits the evolving world around him.

Ilia, too, undergoes a profound transformation—from the dutiful daughter of Troy to a woman of independent will, who catalyzes the opera’s resolution through her own sacrifice. Her first aria opens with the word “Padre”—father—and the whole opera can be seen as a meditation on the evolving meanings of that word. Ilia initially vacillates between love for Idamante and tribal allegiance to Priam and the Trojans (her Aida complex, so to speak) but shows overwhelming courage in her decision to save Idamante, thus prompting the dramatic turnabout of the finale.

Then there is Elettra. A refugee from the myth of the House of Atreus, she represents unchecked passion and vengeful wrath. Her final rage aria, prefiguring the coloratura characterization of the Queen of the Night, is not just a virtuoso showpiece—though Mozart clearly relished writing it—but a depiction of someone utterly consumed by emotional excess.

Perhaps what astonishes most in Idomeneo is the sheer scope of Mozart’s ambition. He poured into this score all he had learned: from the lyrical traditions of Italian opera seria, from Gluck’s dramatic reform, from French opera’s choruses and ceremonial pomp, from sacred music and symphonic craft. The Munich orchestra, steeped in Mannheim discipline, provided him with exceptional woodwinds, and Mozart exploited them brilliantly. The clarinet, for instance—his favorite instrument—features memorably in Idomeneo’s final aria of resignation, “Torna la pace” (which is not performed in the current production).

The score is a marvel of contrasts and cohesion. Mozart moves fluidly between intimate confession and public spectacle, seamlessly linking recitatives and arias into continuous sections. Elettra’s first aria spills directly into the storm scene; the storm itself echoes the internal turmoil of the characters. Musical motifs recur—most famously, the simple descending figure introduced by the winds after the stately chords that open the overture, later associated with sacrifice and suffering. To give the Oracle a special aura, Mozart introduces new, dark colors into the score with a chorus of three trombones and two horns. Idomeneo brims with beautiful melodies, but Mozart does not hesitate to summon the sublime as well.

Idomeneo’s innovation reaches a pinnacle in the unprecedented Act III quartet, the moment that so overwhelmed Mozart at the family keyboard. Each character is locked in their own emotional crisis, and yet Mozart binds them together in musical counterpoint, weaving their private agonies into one breathtaking ensemble.

Idomeneo was not Mozart’s first opera, but it was his first operatic masterpiece and marked his entry into maturity—an artistic coming-of-age in which he reinvigorated handed-down conventions with a new sense of urgency and dramatic truth, reimagining what opera could be.

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator whose work appears in publications including The New York Times, Gramophone, Opera Now, and The Strad. He is the author of Decoding Wagner and The John Adams Reader.

This is a revised and abridged version of an article that was previously published in San Francisco Opera Magazine in 2008.