Commitment to a Classic

Idomeneo is now recognized as his first mature masterpiece, a signal that the former boy genius had become an operatic visionary. But that recognition came late, especially in America. The first known performance in the United States was at the Berkshire Music Festival at Tanglewood in Western Massachusetts in 1947. Among the major American opera companies, Lyric Opera of Chicago was first to stage the piece, during its very first season in 1954.

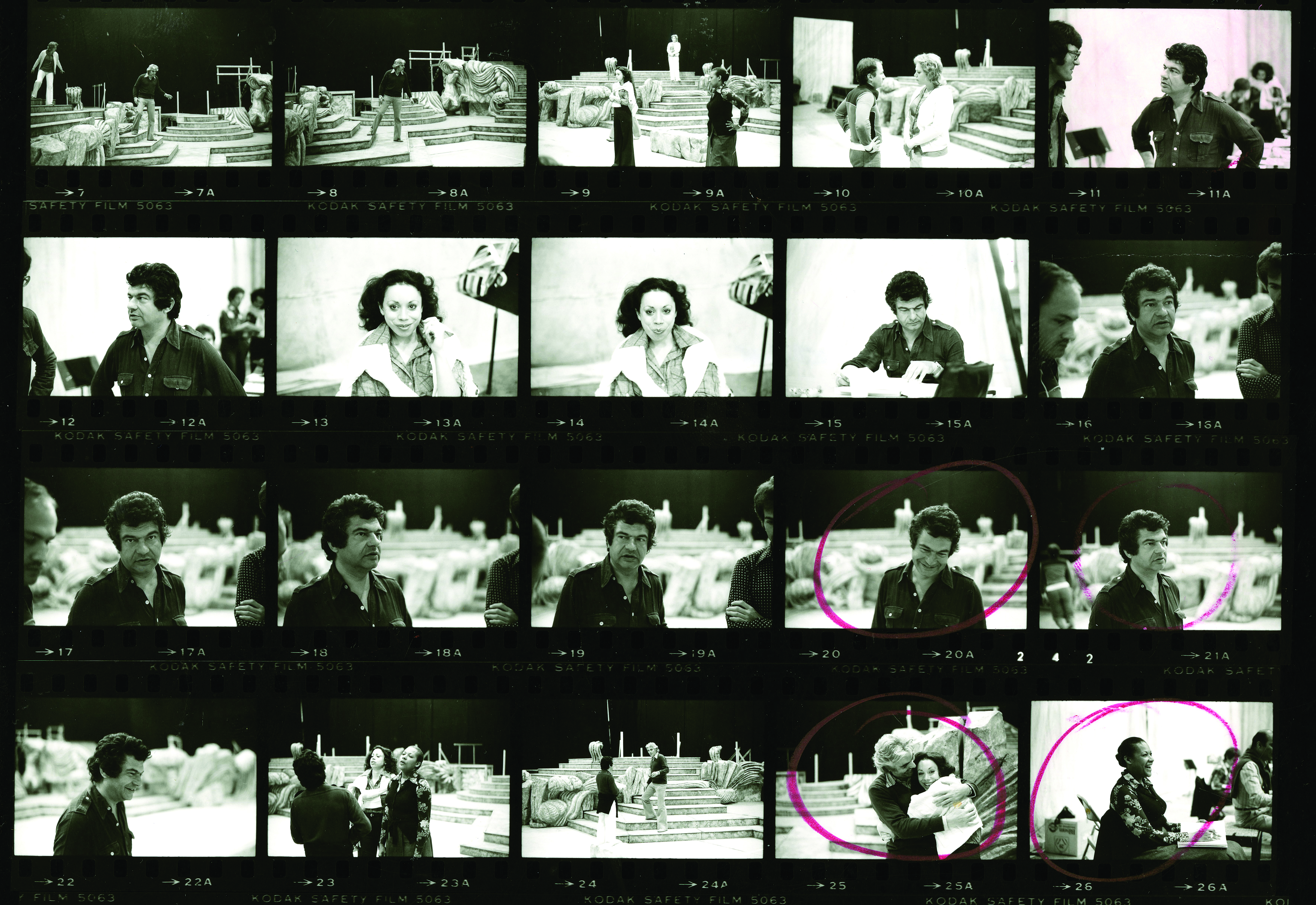

Idomeneo made it to San Francisco Opera in 1977, the Company’s 54th season, with the handsome Swiss tenor Eric Tappy in the title role. (The opera’s premiere at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, in the same production, came five years later.) San Francisco Opera embraced Mozart gradually. His operas were not heard at all during the Company’s earliest years. Le Nozze di Figaro was the first to be presented during the 14th season in 1936. Before long, the War Memorial became a hotspot for the composer’s dramatic works.

Performances of Figaro and Don Giovanni were frequent from the 1930s onward. The Magic Flute arrived in 1950, and the third of the famous trilogy of works with Italian libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte, Così fan tutte, debuted in 1956. Spring Opera Theater, the Company’s off-season affiliate, presented The Abduction from the Seraglio (in English) several times beginning in 1962, as well as Mozart’s opera seria La Clemenza di Tito (sung in English as Titus) in 1971 and 1977.

Performances of Figaro and Don Giovanni were frequent from the 1930s onward. The Magic Flute arrived in 1950, and the third of the famous trilogy of works with Italian libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte, Così fan tutte, debuted in 1956. Spring Opera Theater, the Company’s off-season affiliate, presented The Abduction from the Seraglio (in English) several times beginning in 1962, as well as Mozart’s opera seria La Clemenza di Tito (sung in English as Titus) in 1971 and 1977.

But if Idomeneo was a late arrival at San Francisco Opera, it is nonetheless now firmly established in the repertoire and returns for its fifth presentation this season. Describing the Company’s first production in 1977, Arthur Bloomfield, longtime music critic of the San Francisco Examiner, observed that the opera “came on as a genuinely dramatic, intensely moving work, thanks in considerable part to the creatively stylized, logic-invoking direction of [Jean-Pierre] Ponnelle.” A groundbreaking French designer/director who had been designing sets and costumes for San Francisco Opera since 1958, Ponnelle made his directorial debut here in 1969 with a hit production of Rossini’s La Cenerentola that would be revived often in San Francisco and elsewhere (last seen locally in 2014). His numerous productions, powerfully dramatic in impact and often highly controversial, were to become a major feature of San Francisco Opera’s artistic life for more than three decades, well after his untimely death in 1988 at age 56.

Ponnelle’s stylized neo-classic designs for Idomeneo—in a production on loan from Cologne—were dominated by the giant bas-relief face of Neptune, the sea-god whose wrath over an unfulfilled sacrifice drives the opera’s plot. King Idomeneo’s vow, in exchange for being saved from shipwreck in a storm, was to sacrifice to Neptune the first person he sees on land. As fate would have it, this turns out to be his own son, Idamante, a role composed for a castrato and later revised by Mozart for tenor. Since the original version is commonly performed nowadays, and castrati are in short supply, the part is typically cast as a “trouser role.” Idamante was sung appealingly by mezzo-soprano Maria Ewing in the 1977 premiere run.

Bloomfield gave a vivid description of the storm:

In the interests of exciting theater [Ponnelle] worked the resources of San Francisco’s faithful old Opera House at full throttle, producing, as his pièce de résistance, a shipwreck scene that was a real dazzler: smoke spread across the stage, the great mast of a wrecked ship suddenly appeared through the stage floor, choral sounds sprang forth from the organ lofts on both sides of the house, and then, when the dazed king Idomeneo and his men had safely made their way to the shore, the whole Opera House burst into a flood of light.

Describing the deus ex machina climax of the opera, as the booming voice of Neptune pronounces Idomeneo’s release from his deadly vow, accompanied by portentous offstage brass chords, Bloomfield wryly noted, “Luckily Idamante is saved by a chorus of trombones. The eyes of Ponnelle’s giant Neptunian head dominating the City Hall masonry of Idomeneo’s palace slowly opened, and an oracular voice came forth with the recipe for a happy ending.”

The San Francisco Chronicle’s music critic Robert Commanday was less impressed with the production, complaining of its “excessive gestures and movement and contrived staging,” but—after noting the work as an opera seria, with its formalized structure and lofty moral tone—he was full of praise for the score:

The music is great Mozart (his own favorite work): the arias, dramatic choruses, a superb quartet (possibly the first of its genre), and breathtaking theatrical strokes (like Neptune’s voice accompanied by trombones, foreshadowing Don Govanni and The Magic Flute). The conflict between the mortals and the old gods is conveyed in a conception of genius. Mozart uses the contrast of styles, the forward-looking dynamic of his own dramatic idiom thrusting against the framework of an older stylized operatic tradition.

That first Idomeneo was under the baton of John Pritchard, later to become San Francisco Opera’s first music director. His expertise in the Mozartian repertoire was by then already well established: he had been conducting Idomeneo regularly at England’s Glyndebourne Festival since 1956. In an interview with journalist Allan Ulrich, Pritchard explained his admiration for the opera:

The accompanied recitatives with orchestra hit a level that is absolutely unsurpassable. Really they disrupted the whole focus of opera seria ... And I would go out on a limb and say that Mozart’s treatment of the orchestration is terribly new ... We’ve got to show the public how terribly original the whole opera was and how original it remains.

For San Francisco Opera’s next Idomeneo in 1989, Pritchard, now officially the Company’s music director, would be on the podium again though he was by then in poor health. For the only time in Company history, Pritchard used the version with a tenor Idamante, sung by the debuting Hans Peter Blochwitz, lauded by the Chronicle as “a gleaming discovery.” The role of Idomeneo was sung by Polish tenor Wieslaw Ochman.

The new San Francisco Opera-owned production was directed by John Copley with elegant 18th-century-inspired designs by John Conklin. Chronicle reviewer Commanday approved this time: “Copley, with the conductor John Pritchard, must be praised for ensuring that the music was conveyed in direct personal Mozartian terms. The performance resolved the duality between the formal opera seria style and Mozart’s normal idiom.”

At 5:04 p.m., just three hours before the October 17 performance of Idomeneo, San Francisco got a rough shaking from the Loma Prieta earthquake, causing chunks of ornamental plaster to fall from the ceiling of the Opera House auditorium. That night’s performance had to be cancelled while the safety of the building was assessed. But the shows must go on! Company staff scrambled to find a new venue, and the next Idomeneo and single performances of Verdi’s Otello and Aida were presented in semi-staged concert form at the Masonic Auditorium on Nob Hill.

Ultimately no significant structural damage was found in the Opera House, but to prevent the possibility of loose ceiling plaster plunging down on an unsuspecting patron, a huge fishnet-like mesh was stretched across the entire ceiling of the hall. When performances resumed in the Opera House a few days later, one wag dubbed the experience “Live from the Net.” (The mesh remained in place until renovations began in 1996.)

On a sad note, the final performance in the 1989 Idomeneo run would be Maestro Pritchard’s last public appearance. He succumbed to lung cancer a few weeks after the October 27 performance in the War Memorial at age 68. Fittingly his last act on the podium was leading an opera he especially loved and had championed throughout his career.

The stylish Copley/Conklin production of Idomeneo would be seen here again in two subsequent seasons, conducted in 1999 by Music Director Donald Runnicles, with Swedish tenor Gösta Winbergh as Idomeneo. Runnicles was on the podium again for the 2008 revival with American tenor Kurt Streit in the title role.

After a seventeen-year absence, Idomeneo appears once more at the War Memorial, conducted by Music Director Eun Sun Kim. (Music directors always seem to want first dibs on conducting this piece). Lindy Hume directs her production from Opera Australia (Sydney) and Victorian Opera (Melboune) featuring projections inspired by the surging seas and craggy coasts of Tasmania. The set designer is Michael Yeargan, who created San Francisco Opera’s co-production of Wagner’s Ring, and with lighting by Verity Hampson and striking video projections by David Bergman.

Distinguished tenor Matthew Polenzani returns as Idomeneo, a role he has sung to acclaim at the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the Royal Opera Covent Garden. Daniela Mack reprises the role of Idamante; Ying Fang makes her Company debut as Ilia; and Elza van den Heever is Elettra.

In the context of this legacy of notable past productions by Ponnelle and Copley and of strong musical leadership by Pritchard and Runnicles, the return of Idomeneo in 2025 in an eye-catching new production offers a reminder that our enjoyment of Mozart’s operas need not be confined to the “fab four” he composed during his thirties: Figaro, Giovanni, Così, and Flute. Idomeneo’s singular status in the Mozart canon was aptly described by scholar Julian Rushton who called it: “an opera sui generis, occupying a special place in the affections of its composer, who went on to other achievements as vital and significant, but never returned to its dignified, heroic, yet thoroughly human world.”

Clifford “Kip” Cranna is Dramaturg Emeritus of San Francisco Opera.