From Ancient to Modern: A Tasmanian Idomeneo

David Bergman and Lindy Hume

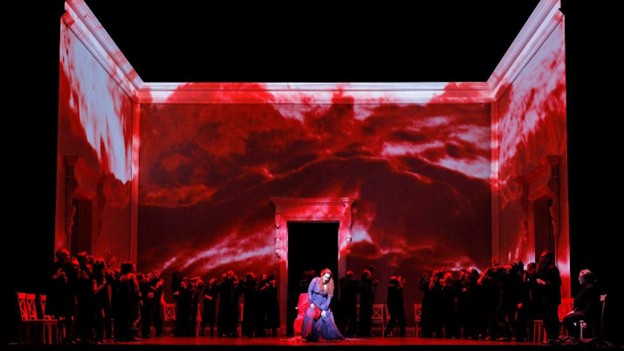

The projected world of Mozart’s Idomeneo in our new-to-San Francisco production. Photo Cory Weaver.

The projected world of Mozart’s Idomeneo in our new-to-San Francisco production. Photo Cory Weaver.

Lindy is the third Australian director whose work has been seen on our stage in the last twelve months. Last summer, our productions of Innocence and The Magic Flute came from Australian directors Simon Stone and Barrie Kosky. Lindy joins them as a visionary whose work we are delighted to see in San Francisco for the first time this summer.

This production of Idomeneo came from Opera Australia (I saw it in Sydney in early 2024 after we had already chosen to take the production). Lindy was curating part of the Opera Australia season in 2024 and wanted to add to the number of productions after the long tail of Covid had led to a shortage of stage crew to change over operas night tonight. She came up with the wonderful idea of creating a production out of existing elements that could work for not just one but two operas.

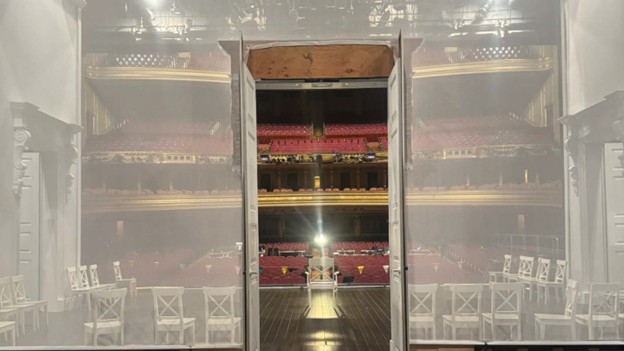

Scouring the Opera Australia stores, she came across a three-sided gauze room, replete with classical doors, that had been designed by Michael Yeargan (our Ring designer) for a production of Massenet’s Werther. Working with Opera Australia’s technical team, she developed a stage framework that could work for both Idomeneo, which she would direct, and The Magic Flute, directed by a different director. The difference would be that Magic Flute would stay completely analogue, while Idomeneo would be completely digital. The scrim walls (a kind of gauze) become projection surfaces, fed by three projectors directly above the stage, one for each wall. It’s a space that can be as intimate or expansive as the imagination allows.

Looking out to our opera house through the scrim walls of the Idomeneo set.

Looking out to our opera house through the scrim walls of the Idomeneo set.

Lindy had already worked with projection designer David Bergman (Tony-nominated this year for The Picture of Dorian Gray) on a staging of Schubert’s Winterreise, so there was already a fluency between the two of them, working first in the studio to storyboard and plan the arc of the storytelling. As a foundational principle, they decided that they wanted to reflect the ancient nature of Crete—the largest of the Greek islands and the setting for Idomeneo. But they wanted to bring that ancient space into more immediate relief for a Pacific, not Mediterranean, audience. So, they focused on the island of Tasmania, the island off the southeast corner of Australia, with a population of about 500,000 and an area roughly equivalent to West Virginia. Tasmania is one of the most ancient places in the world, with parts of the island completely inaccessible and home to ancient, old-growth forests. There are places of true wilderness, an ancient land with an ancient mythology of first peoples. It was a perfect analogy for the themes of Idomeneo.

The craggy landscape of Tasmania, photo David Bergman

Lindy worked with cinematographer Catherine Pettman and Sheoak Films to capture footage specifically for this production. Everything that you will see projected is taken from real, natural imagery, much of it filmed with drone cameras. There is no computer generated imagery used in the production.

Catherine Pettman and her team taking a drone selfie while filming in Tasmania.

Catherine Pettman and her team taking a drone selfie while filming in Tasmania.

As I’ll discuss in a moment, some of the imagery has been adjusted, but its basis is always the real nature of Tasmania, beginning with the albatrosses that fly overhead during the overture, filmed on location on Albatross Island, off the north-west tip of Tasmania.

Albatross Island, photo Catherine Pettman

Lindy and David story-boarded out the whole production before filming to determine what they wanted in each scene, so that Catherine and her team had clear directives for what to film. But the cinematography team did come up with some footage that inflected the production. A great example happened when the team was filming drone footage over the Tasman Sea. As they looked at the monitor, a strange shape came into view—a dark mass undulating in the water. It was a kelp island, rippling and morphing as though breathing and alive. The conundrum of what to use for the sea monster in Idomeneo was solved! You’ll see it in close-up as the sea monster turns on the island when Idomeneo (played by Matthew Polenzani) fails to uphold his vow.

The kelp island floating in the Tasman Sea, photo Catherine Pettman

The sea monster in its projected state, photo David Bergman

Some of the imagery you will see is very realistic, as with the use of Albatross Island for the overture (centering us clearly on an island) or the forest at the top of Act III which is footage shot in the Tarkine, or Takanya—a vast wilderness area in northwest Tasmania.

The Tarkine, photo Catherine Pettman

The projected imagery onstage, photo Cory Weaver

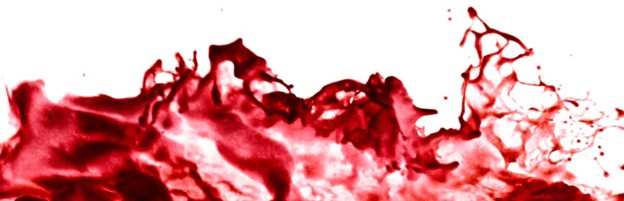

Other imagery is taken from natural source material and then manipulated to create some incredible effects. One of my favorites is towards the end of the opera when the Elettra character (played by Elza van den Heever) rages as she realizes she will never have the man she loves. As Elettra summons up the furies, the walls become an intense red blood. But the blood is actually sea-foam from off the rocky Tasmanian coastline, adjusted by David using DaVinci Resolve editing software. David pulls out close-ups of the sea-foam and then colorizes it red. The results are stunning.

The development of a projection: from raw footage to a projection onstage, photo Cory Weaver

The interaction of cinematography and digital editing makes for some incredible imagery. Some of the footage (e.g. the albatrosses at the start) was shot with a slow-motion camera. But much of the footage was shot in real time and then digitally slowed down and smoothed out. Some of the footage runs 500-times slower than real-time, allowing for an incredible elongating of time.

Both Lindy and David were determined from the beginning to ensure that this not be an opera about screens. The imagery must always be in service of the human emotion that is playing out on stage. The action must be centered on a human scale, a human voice and a human dilemma. This means that we’re not always looking at moving images. And herein is the delicate balance for any projection-based show. You are not creating a three-hour film. You are creating spaces for emotional exploration. As such, only about a third of the opera incorporates dynamic video; at other times there may be sky sequences with very slowly gathering clouds; and at other times we are in a much more internal space in which projection uniquely enhances the contours of the architecture, creating for a powerfully vivid indoor space.

The set in its pure state. The architectural details are projected onto the physical elements to create a very impactful image. You can just make out the boxes housing two of the projectors above the stage.

Projected scenery can bring its own nuanced challenges, and one of the things we had to be particularly careful about was sound reflectivity. The set itself is all fabric, save for a few hard door frames. On a stage as big as ours and in a house as big as ours, one needs physical surfaces to reflect sound out from the stage to the audience. To help with this, our scene shop built two huge 30-foot high black walls, each weighing 450lbs. They sit upstage (or just behind) the rear wall of the set. They are painted in a matte black paint, very intentionally chosen to ensure no reflectivity of the projection, and allowing the walls to recede into a complete void.

The intersection of lighting and projection is also critical. The original lighting design was by Verity Hampson, with the production here being lit by our lighting director, Justin Partier. It is a very delicate balance, ensuring enough light to see the faces and emotional connection of the artists, without washing-out the projection images. That is particularly challenging with a completely gold, reflective proscenium arch as we have here! But both Verity and Justin are incredibly talented in finding that precise balance!

Idomeneo is an opera that integrates the epic with the intimate—the vast canvas of nature at its most fearsome and awe-inspiring, and then the most vulnerable love of two young people trying to find their way in the world. There is something incredibly powerful about what Lindy, David and the rest of the creative team have created, using both projection but also very the nuanced dramaturgy of human relationships to convey the complete arc of humanity. A world in which we feel at once the monumental might of nature, and the delicate fragility of the human experience. I cannot wait for you to experience it!

Matthew Polenzani as Idomeneo. Photo: Cory Weaver