Backstage with Matthew: The Form, Function and Fichus of Figaro Fashion

In a prior edition, we explored the background to some of the fabrics being selected by costume designer Constance Hoffman. Much has happened since then, and all the costumes are now created and in active use. Just prior to the piano dress rehearsal I sat down with Constance, Daniele McCartan (SFO’s Costume Director) and Galen Till (the Costumes Supervisor on Figaro) to find out what they would be focusing on in this rehearsal.

A piano dress is the final rehearsal before we add in the orchestra. It is usually a long rehearsal (4-5 hours) in which the director will work through the whole opera, adding in costumes for the first time. This is the most important rehearsal for the costume team because it is the first time they will see the costumes under theatrical lights, and the only time they will have to make significant changes to the costumes. Things like white shirts can look very different under certain theatrical lights than they do in a more traditional environment. And changes in lighting technology (with a move to LEDs) create different implications for costumes – it’s an interesting transitional time for the intersection of lighting and costume.

From a costume perspective, the piano dress rehearsal is used for both aesthetic and functional purposes. Aesthetically, Constance will be working with other members of the design team to ensure that colors are working well, that the costumes are helping support the story-telling in the most powerful way, and that the overall look and feel of the show is as intended.

From a functional perspective, Daniele and Galen are working with their teams to ensure that the costumes are working as smoothly as possible for the artists. Principal artists are generally fit for their costumes on the first day they arrive (giving time for the costume shop to make adjustments), but this means that artists have not yet seen their staging. As a result, functional costume questions around things like pocket placements, how to quickly remove a cape, how quickly a jacket can be buttoned, etc. are not always known at the time of the fitting, particularly for a brand new production like this. This is the rehearsal when much of that is finalized.

The Marriage of Figaro is a particularly busy and theatrical show from a costume perspective. There are disguises, multiple looks for characters, and a larger-than-usual amount of notes/letters/songs that need to be squirreled away in pockets, up sleeves, etc. In Constance’s words, this opera is “pocket central!”

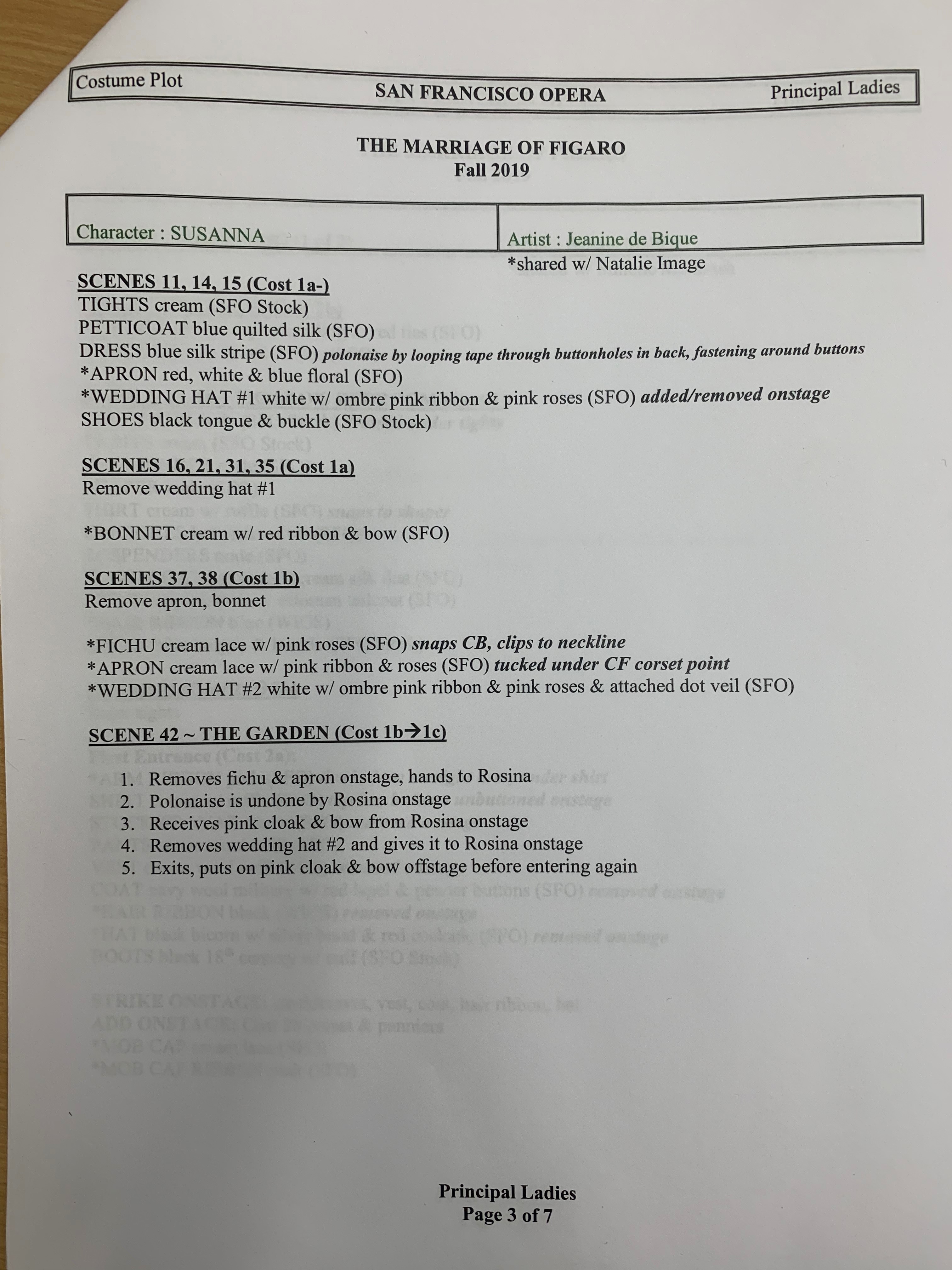

Some of these logistical needs are taken care of during the staging process. Each day, notes are given from the rehearsal room to a variety of departments including the costume shop. One such note was for Susanna to have a pocket in her apron in which to hide a letter. Constance tells me that, in the late 18th century, pockets were generally not found on women’s clothes (rather they would have slits in clothes that provided access to pouches) and so she had to come up with a cunning design that would be aesthetically plausible, but also achieve the necessary functional use. The piano dress was the chance to test out whether it worked (it did!).

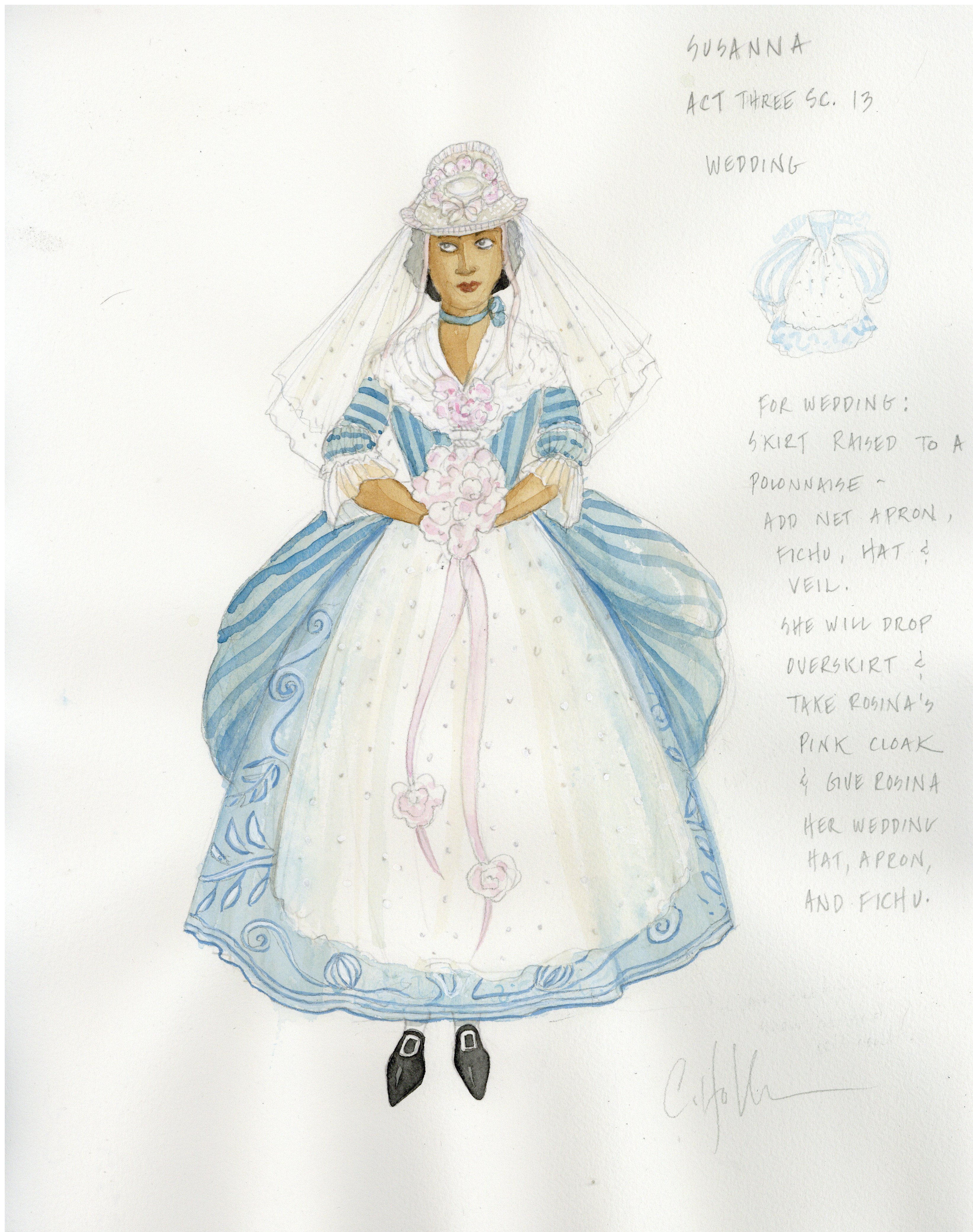

There are some very clever solutions to the logistics of costumes that you won’t see in Figaro but are wonderful examples of how the dramaturgy works with the realities of clothing. Susanna has a wedding bonnet that needs to be quickly attached and removed at various points in Act I and Act IV. If she were wearing the bonnet for real use, it would be affixed with several hat pins. But there is no chance to do that in the time she has on stage, so our Susanna (Jeanine De Bique) has magnets built into her wig, with corresponding magnets on the hats! She also has two hats – one for Act I when it needs to be thrown around, and one for Act IV that has the lace veil for the night-time disguise.

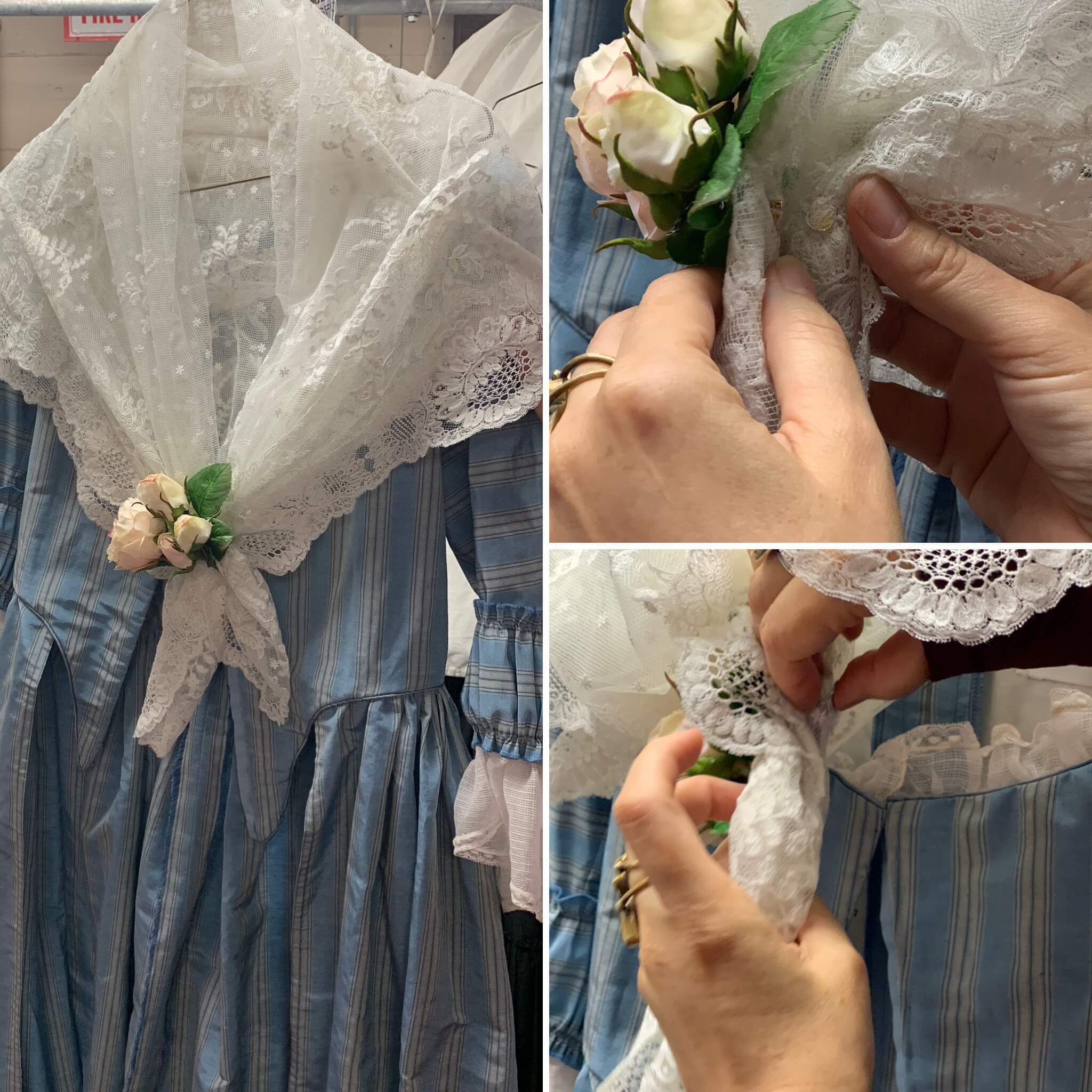

There are similar magnet solutions for fichus (lace that sits just above the top of a dress) – enabling a costume piece to remain in place, but in a way that is immediately removeable!

Other logistical elements that the costume team are looking at during the piano dress include hem lines and “rigging” (snaps, hooks and buttons). Daniele McCartan tells me that there is nothing worse in a costume than a bad hem line – it’s the first thing that she’ll see when looking at a costume onstage. When costumes are being constructed, Constance says that she will get down on her hands and knees to look at a hem line – that approximates much more the view of the audience sitting down in the auditorium. So a lot of work is done to examine hem lines, and see how tight sleeves and bodices are, etc. Our drapers are there in a piano dress so that they can see these realities of the costume first hand and work with Constance, Daniele and Galen to create solutions. The next time the costumes are seen are often the final dress rehearsal, and so we need to be sure that the solutions are as likely to succeed as possible.

As Costume Supervisor, Galen is both looking at the costume functionality and aesthetics, but also translating all the notes and changes into specific actionable strategies that will then get worked on in the days following. She is on headset during the rehearsal and is the liaison between all of the costume and wardrobe teams. She can ask the wardrobe team (dressing the artists) to try something new based on what is being seen in the front of house. Typically things like hems won’t get adjusted mid-rehearsal, unless they are posing safety concerns for the singers, but the specifications for an adjustment are recorded and clarified for post-rehearsal work.

There are a number of really wonderful costume shifts that happen in Figaro, including the disguise of Susanna and the Countess as each other in Act IV, while they are trying to trick the Count. Constance has come up with a fascinating costume solution whereby Susannah is able to adjust her wedding dress to be more Countess like, and the Countess able to hoist up her dress to have more of a Susanna feel. Seeing that kind of adjustment onstage is so important during a piano dress.

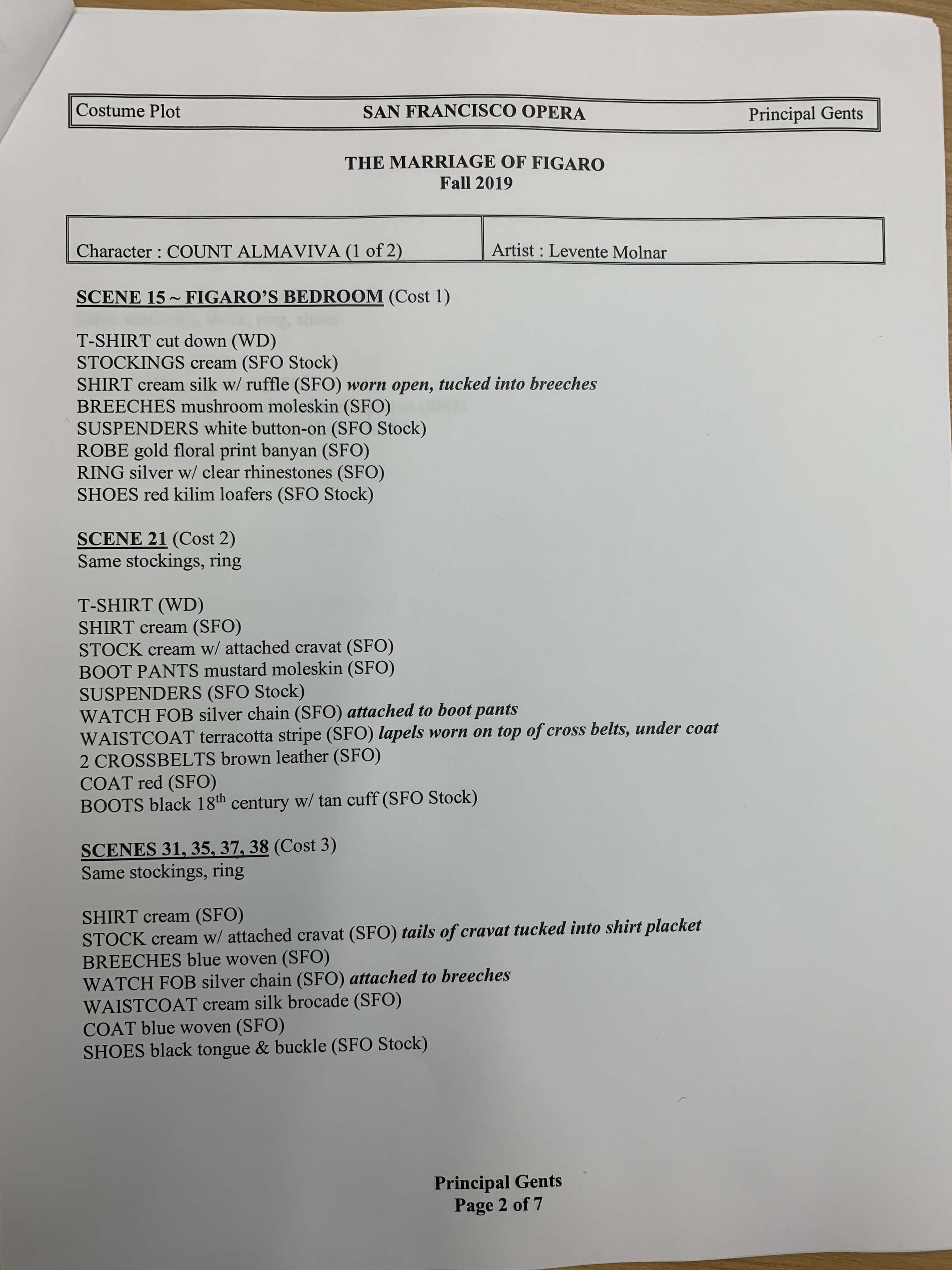

In any opera there are many notes that need to be captured about costumes, but particularly so in a busy show like Figaro. Paperwork is so important to the costume team, and we pride ourselves on keeping very specific paperwork – information not only about what went into creating the costumes, but which characters wear which pieces, and when. These notes are critical to the wardrobe team. There is also a costume breakdown which catalogues every item used in the production – particularly important when the production is being rented. This all then feeds up to the master run-list: a document kept by stage management that chronicles every single element happening in the production.

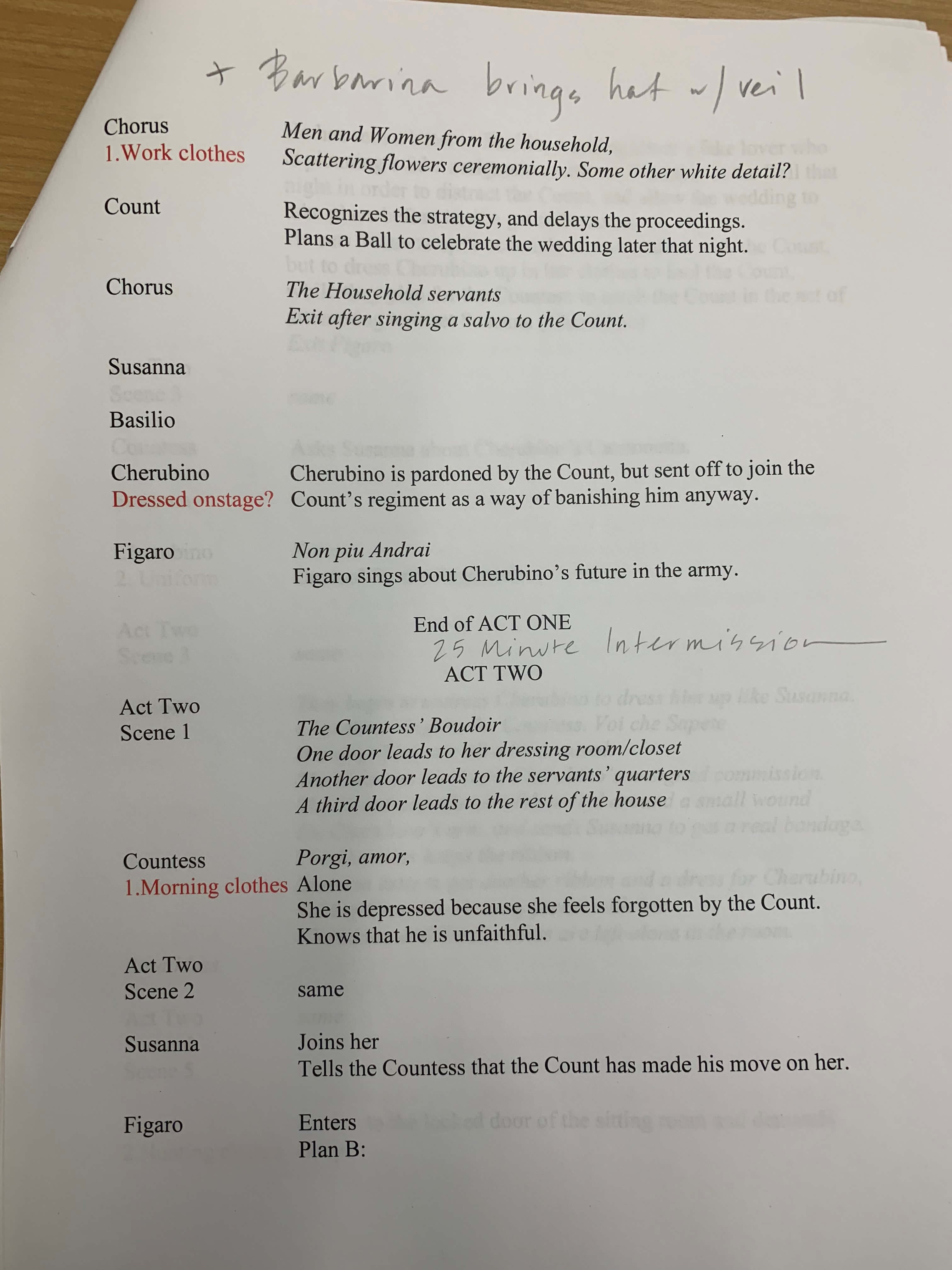

Constance also keeps her own paperwork: when she starts working on a production, she will create her own breakdown in which she summarizes the plot and punctuates it with specific needs for costumes (e.g. Antonio enters in his gardening clothes). This really helps Daniele budget a show that does not yet exist, because it gives a clear sense of how Constance is thinking about the arc of who is wearing what and when.

In the piano dress, all of these elements – logistics, aesthetics, form and function – come together and, for a busy five hours, the costume department is observing, reacting, adjusting, discussing and solving real-time problems such that the final dress can be as smooth as possible.

Based on what we saw at the piano dress we are in for a wonderful treat with the costumes of Figaro. Constance’s designs and the artistry of our costume shop have come together in a really beautiful way. I am so excited to share this new production with you in October!