A Woman Cheers: Candace Zander Kahn’s Lifelong Operatic Odyssey

She has been part of the San Francisco Opera for more than forty years, in one form or another—as an audience member, supernumerary, educator, donor, and advocate. The Chronicle image captured her in the act she has repeated countless times: honoring the art form that has threaded through her life.

1. Candace as Countess of Aremburg with soprano Carol Vaness in Don Carlo (1992-93) 2. Candace with mezzo-soprano Nina Terentieva as Elizabeth (Elisabetta) of Valois in Don Carlo (1992-93)

The First Time

It began in 1973 with the San Francisco Chronicle that Candace’s husband, Harry, brought home. “Harry came home holding a newspaper like it was a treasure. There was this Rigoletto photo in color, almost unheard of then. We bought tickets that day.”

In that instant, the Jean-Pierre Ponnelle production became their first Opera, opening the door for what was to come. The pull was immediate with music, voices, costumes, and drama. It triggered a lifelong devotion they shared as a couple and as individuals. Candace didn’t yet know it, but that same production would one day put her on the stage, becoming a key part of her own story

The following years led Harry and Candace to be deeply moved by the powerful scores of all the great opera composers. Candace was a trained dancer and no novice to the stage. On a whim, Candace applied for a supernumerary role, knowing she and Harry were leaving for a language course in Italy. The trip had its complications, making Harry and Candace come home early. “We just got home, Harry was opening the door and we could hear the phone ringing,” said Candace. “I ran to it, I don’t know why, no one knew we ended our trip early. It was San Francisco Opera, they asked if I’d like to try out for a Super part in Rigoletto.” It was the summer season of 1981.

Stepping Onstage

With Rigoletto, Candace traded her view from the audience for the wings of the stage. She joined the company as a Supernumerary, typically one of the non-singing, non-speaking characters that lend realism to the world of an opera. “In Rigoletto, I appeared as Monterone’s Daughter in Act 1 and came back in the third act as the spirit of the dead Gilda. She repeated these performances in the 1984 and 1990 revivals of the production.

Candace as Monterone’s Daughter in Rigoletto (1981)

“Performing on the opera stage played a large role in transforming me from introvert to extrovert,” said Candace. More so, it gave her friends, a community, and memories that have defined her life. She remembers her first time working under Kurt Herbert Adler during his last year as General Director, “A true impresario.” She said, “Adler often talked about bringing opera to the people, which he did via Opera in the Park, Fol de Rol, and Brown Bag Opera. He was ahead of his time.”

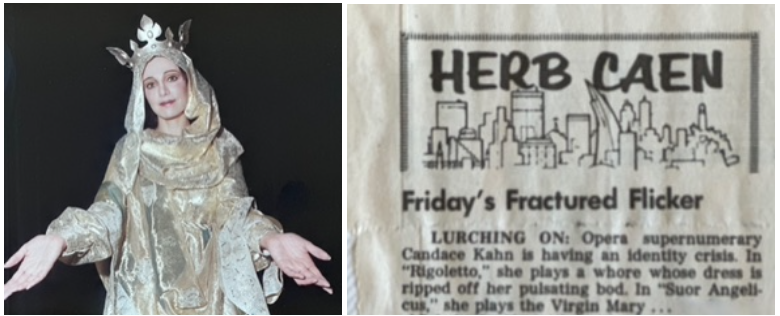

1. Candace as Virgin Mary in Suor Angelica (1990-91) 2. Journalist Herb Caen, SF Chronicle (1991)

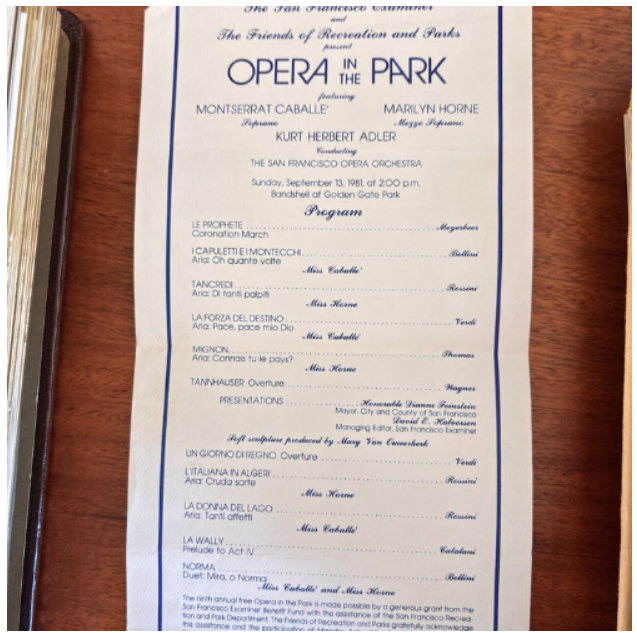

In the Fall of 1981, Candace appeared as Princess Azema in Rossini’s Semiramide. The role is ordinarily performed by a singer (the director had muted her). This unusual part gave Candace the rare opportunity to rehearse and perform with the great stars, Marilyn Horne and Montserrat Caballé. The Sunday after opening night, she watched Horne and Caballé perform in front of the bandshell in Golden Gate Park for Opera in the Park with Adler conducting.

1. Candace as Azema in Semiramide (1981-82) 2. Candace with Barbara Rominki, Director of Archives, looking at her Semiramide scrapbook

In 1982, she again appeared with Marilyn Horne, but this time as a humble handmaiden, with Joan Sutherland, in Bellini’s Norma. Candace dubs both of them “The nicest people you could meet. The biggest stars were the nicest people to their colleagues.” The part may not have been significant, but experiencing the audience’s thunderous applause after Sutherland’s “Casta Diva” was a peak experience in and of itself. This was the same year that the two opera stars sang together in Opera in the Park with Adler conducting.

Opera In The Park program with Montserrat Caballé and Marilyn Horne (1981-82)

After 10 years and 74 performances, with Harry sending her flowers each opening night, no matter how large or small the part might be, Candace retired from the opera stage “on top” after playing in the lead cast as the Countess of Aremberg in Don Carlo (1992). Nonetheless, the opera didn’t leave her.

1. The Hammy Award. Supernummery award by Supers for Supers. The award went to Candace for her role in Manon Lescaut (1988) 2. Candace as The Countess of Aremburg in Don Carlos (1986) in front of Dressing Room 20

Opera in the Classroom

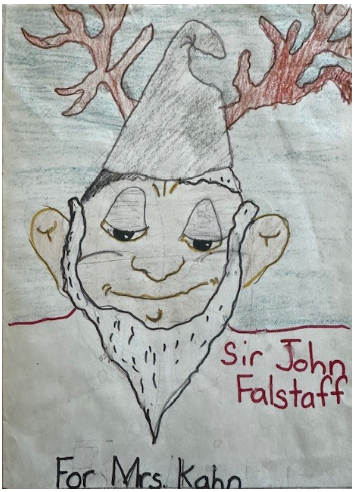

Throughout her time as a Supernumerary, Candace had also been a Middle School teacher at Sequoia K-8 Academics + School in the Mt. Diablo Unified School District. Throughout her teaching career, she found ways to incorporate the arts, primarily opera, into the classroom curriculum. After she was no longer a Supernumerary, she created opera activity booklets that coordinated with the San Francisco Opera Guild’s Student Matinee performances. The Opera Guild adopted and distributed her writings to teachers throughout the Bay Area, who were escorting their students to the matinee performances. They were designed to spark curiosity in young students. A gifted student drew the La Bohème Café Momus scene entirely from memory; the Guild used it as the cover of its program. “My students learned opera by using their creative instincts.”

Walking into the Opera House lobby one evening, Candace was surprised to see sets for Falstaff that her students had designed in every corner of the lobby. They were on display there all season. For her, it was as thrilling as any stage call. Decades later, an adult stopped her on Market Street saying, “You took me to my first opera, and I still go!” he said excitedly. For Candace, that moment was better than any award.

Student drawing for Falstaff (1989-90)

Holding On To Harry Kahn

At thirty-five, Harry teetered dangerously close to death’s edge, enduring a harrowing six months in the hospital, a crucible that transformed the rhythm of the Kahn household overnight. Candace, faced with the stark proposition of losing her partner, drew a hard line with fate: if Harry was to survive, everything had to change. She immersed herself in the disciplines of nutrition, determined not to leave his recovery to chance or guesswork. What began as fierce personal research soon became a blueprint for Harry’s longevity, a regimen rigorous enough that, in Candace’s hands, it earned him an unexpected twenty-five additional years.

Candace and Harry (2004)

But Candace never functions in half measures. Her private campaign morphed into a public crusade, as she secured classroom, school-wide, and eventually district-level grants to overhaul how children learned about food and health. This upward arc brought her to the notice of the California State Board of Education, where she spent six years—first as a member, then as chair—of the Child Nutrition Advisory Council (CNAC). In those roles, she helped shape policy not only for California’s schoolchildren but also in concert with national partners, such as the USDA.

Yet it was never policy for policy’s sake. Candace authored “Nutrition Competencies for California’s Children,” producing pragmatic frameworks aligned with state standards and distributing hands-on curricula to organizations like the Dairy Council, along with recipes, lesson modules, and activities adopted from Humboldt to San Diego. Ever the teacher, she infused her work with faith in potential as much as knowledge, striving to grow health and agency in equal measure.

Her educational vision expanded into engineering and architecture as well, when she devised an innovative curriculum that invited students to study the seismic and technological wizardry behind the new Eastern Span of the Bay Bridge and imagine their own design concepts. Their models, celebrated with a six-month residency at the Oakland Museum of California, underscored Candace’s guiding creed: whether the material is food, a bridge, or grand opera, citizenship means building and leaving something of value behind. The Opera remained a constant in a life reordered around caregiving. The art form they had loved together became, in those years, a lifeline.

A Requiem for Harry (2009)

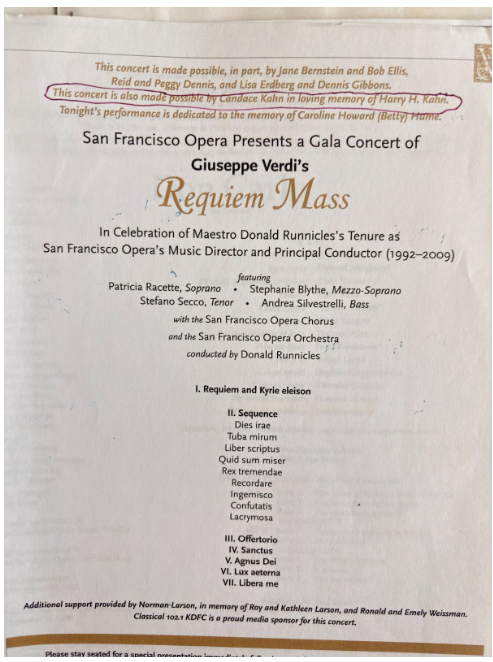

Before Harry died in 2008, he shared with his wife what he wanted: music. A performance of Verdi’s Requiem in his honor.

The following spring, Candace called the development office to ask about making a contribution and having his name in the program. She had to stay persistent; it wasn’t an easy ask to accommodate.

Harry at the San Francisco Symphony’s Black and White Ball (1988)

The night of the concert, she drew on her strength and acceptance that there is a beginning and an end to all things. She looked at the Art Deco chandelier and the Beaux-Arts-style architecture, recalling the young Candace and Harry’s pursuit to save San Francisco’s mid-century Victorian homes. They attended historic lectures and tours, and she worked with the San Francisco Architectural Heritage, where they protected 19th-century homes from demolition. She recalled Harry’s zeal for building their weekend retreat at The Sea Ranch and the way he held her hand as they listened to Calvin Simmons’ Verdi Requiem with the Oakland Symphony.

She opened her San Francisco Opera Requiem program and saw the line: In loving memory of Harry H. Kahn by Candace Kahn. “It was the fulfillment of his wish,” she said, “and the very moment I recommitted to opera.”

Verdi’s Requiem Mass in honor of Harry Kahn (2009) / Courtesy of Candace Zander Kahn

The Donor Years

Her commitment now resonates at the level of the Producer’s Circle, where philanthropy takes the stage alongside artistry. Candace’s ongoing devotion to Verdi serves as both a tribute to Harry and as a kind of living memory—a thread tying her past to every golden curtain rising. At the same time, her passion for fresh voices and inventive opera ensures that world premieres, such as The Monkey King, find a home in the city of San Francisco and in the future she helps to build.

Candace Zander Kahn wearing The Monkey King t-shirt (2025) / Courtesy of Candace Zander Kahn

The Chronicle’s “A Woman Cheers” photo captures only a fraction of Candace’s story; a single frame distilling years of lived history. Behind that instant lingers the memory of a rare 1973 color spread that ignited a lifelong passion, the mention in a Herb Caen column, the delight of watching her students’ artwork grace the Opera House, a program listing in honor of her husband, and the cherished faces of friendships formed both behind the curtain and among the audience—each one a note in her decades-long symphony.

Candace Kahn still cheers. And San Francisco Opera is richer for it.

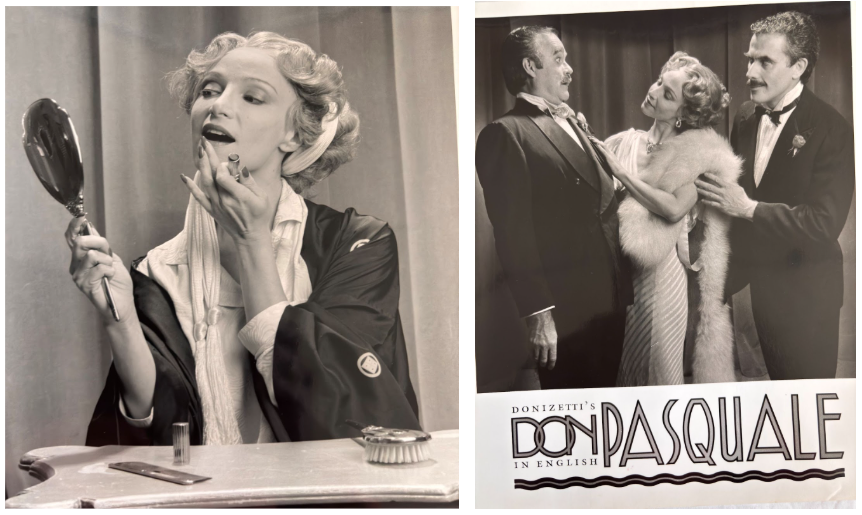

Candace as Norina in a Don Pasquale photoshoot (1986) for Western Opera Theater. / Courtesy of Candace Zander Kahn