Donor Spotlight

Aria in the Wings: The Pride of Thomas E. Horn

A civil rights attorney, publisher, philanthropist, and trusted statesman, Horn has never sought the spotlight. Yet his influence is unmistakable, from courtrooms to concert halls, from pressrooms to policy chambers. His legacy is not carved in bronze but inscribed in lives changed, institutions protected, and voices empowered.

From his Nob Hill apartment, where a 19th-century oil painting of Monaco’s harbor hangs with austere grace, Horn observes the city he’s helped nurture. The painting, brushstrokes bold but restrained, feels like a reflection of the man himself: refined, luminous, and quietly commanding. It doesn’t ask to be noticed. But for those who look closely, it reveals everything.

Born Gay

Thomas Horn was raised in Albuquerque during the 1950s and 60s. It was a time when being gay was not just taboo; it was illegal, invisible, and unspeakable. “I didn’t want to be gay,” he says with candor. “I wanted to be president.”

In college, Tom asked his father, a self-made oilman who had survived orphanhood, to send him to a psychiatrist. He told the psychiatrist, “Make me different.” But the doctor offered a redirection. “I can’t help you change, But I can help you accept. I can help you adjust.”

“I thought he was useless,” Tom says with a dry smile. “Turns out, he was brilliant.”

Thomas Horn senior picture; campaigning for student council; with first car / Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Horn

Thomas Horn senior picture; campaigning for student council; with first car / Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Horn

Tom Horn never became president. But he became something this country arguably needs more: a guardian of justice, a defender of those left outside the margins. At 25, fresh out of UCLA Law, Horn went back to New Mexico and immersed himself in public defense. “I represented everyone they threw at me,” he says, And when no one else would defend gay men caught under sodomy laws, he did. Not because he saw himself as an activist for gay rights, but because he couldn’t abide by rules that made humans illegal.

Years later, when Horn sat down with his father over lunch, his father finally broached the subject. “Are you happy?” he asked. Tom nodded. That was the whole conversation. His father nodded with him.

The Law as a Lantern

Before his time in San Francisco, before his numerous appointments to executive boards, international accolades, and philanthropic endeavors, Thomas Horn stood in fluorescent-lit courtrooms, defending those often overlooked by society. “Because I was trying all these cases for the down-and-outers,” he says, “I came to the attention of the ACLU.”

In the 1970s, the ACLU of New Mexico was one of the strongest state chapters in the country, boasting nearly 200 volunteer attorneys, many of whom were from the state’s most prestigious firms. The legal director at the time, Chuck Daniels, a law professor and close friend of Horn’s, called him one day with a proposition: Take over for me. “I was young and dumb,” Tom says now, “so I said okay.”

And just like that, he became legal director of the New Mexico ACLU, a role that gave him the first, formidable taste of how the law could be wielded not just as a profession but as a principle.

“It was kind of like being in arraignment court on a Monday morning,” Horn says. “Every case came through my hands first. I got to decide what we would take on.” He didn’t take the ones that were clean or easy. He took the ones that mattered.

At the time, sodomy laws still criminalized gay existence across much of the country. One state Supreme Court had recently struck theirs down, and Horn was paying attention. By then, he had been traveling to San Francisco frequently, keeping abreast of the legal developments within the gay rights movement. He was observing and learning where the cracks in the old systems were starting to show.

Then came The Armstrong Case. “It wasn’t the perfect test case,” he admits. “Legally, it was rough.” The facts, he knew, were flawed. But he saw an opening. “I argued that the statute under which the case was charged, the sodomy law, was unconstitutional.”

https://www.aclu.org/documents/getting-rid-sodomy-laws-history-and-strategy-led-lawrence-decision

He lost the case. But he won something more lasting. “There was a judge on the Court of Appeals, Lou Sutton. Old-school Albuquerque, his family had founded one of the big firms there. But he saw the merit. He agreed with me. And he wrote a dissent that was strong, really strong.”

That dissent would echo beyond New Mexico. It would be cited in later cases across the country as lawyers fought, and eventually won, the battle to dismantle sodomy laws altogether.

Horn doesn’t tell this story to boast. He downplays the impact. “I didn’t make money off any of it,” he says. “But I wasn’t in it to build wealth. I wanted to pay my staff and the lawyers who worked for me, and I did. That was enough.”

For Horn, law was never about prestige. It was about presence. About standing somewhere no one else wanted to stand and simply not leaving.

“You learn, as a lawyer, that if you want to challenge something, really challenge it, you need good facts. I didn’t always have them. But I always had purpose.”

The City

By 1976, Tom Horn had moved to San Francisco permanently, joining a city that, like him, was learning how to breathe in its whole identity. “I didn’t come to march. I didn’t come to riot. I came to live around people like me.”

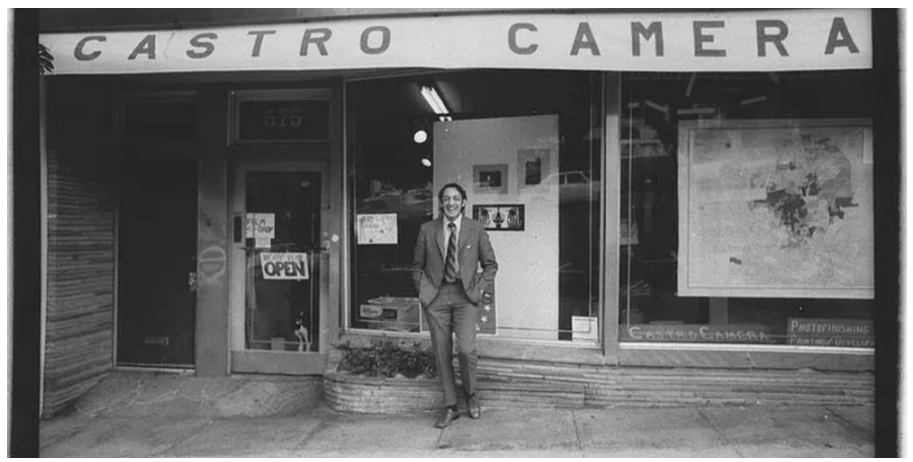

In the late 1970s, developing photos wasn’t just about snapshots on a Kodak; it was a test of trust. “Someone said to me, ‘You need to meet Harvey, he’s running a camera shop on Castro Street,’” Tom Horn recalls. So Tom walked into Castro Camera. And into history. There was Harvey Milk, surrounded by his orbit of youthful, passionate acolytes, Cleve Jones, Dickie Pabich, and Jimmy Rivaldo. “Little Harvey groupies,” Tom calls them.

Harvey Milk in front of his shop Castro Camera in 1975. (Photo: Courtesy of Getty Images/Janet Fries)

Harvey Milk in front of his shop Castro Camera in 1975. (Photo: Courtesy of Getty Images/Janet Fries)

“I get to know Harvey, I start talking with him, and we become friends. I learned right away that Harvey was interested in politics. And so I supported him. Tom wasn’t aligned with any political machine, not Burton’s or Willie Brown’s rising circle. “I didn’t know any of them,” he says. “I wasn’t part of that world.”

The city changed its election rules. Supervisors would now be elected by district rather than at-large. It was a quiet structural shift, but for Harvey Milk, it was the doorway. “Harvey ran from the Castro,” Tom says. “Of course I got involved in the middle of that. I campaigned for him.”

1. SFLGBT Pride Parade (1978) / SF Gate 2. Anne Kronenberg driving Supervisor Harvey Milk in the SFLGBT Pride Parade, (1978) Photograph: Daniel Nicoletta / Harvey Milk meeting President Jimmy Carter (May 21, 1976) / Harvey Milk Foundation, http://milkfoundation.org/

1. SFLGBT Pride Parade (1978) / SF Gate 2. Anne Kronenberg driving Supervisor Harvey Milk in the SFLGBT Pride Parade, (1978) Photograph: Daniel Nicoletta / Harvey Milk meeting President Jimmy Carter (May 21, 1976) / Harvey Milk Foundation, http://milkfoundation.org/

Milk’s victory was a breakthrough, not just for LGBTQIA+ representation but for anyone who had ever lived outside the margins of political power. He was the embodiment of unapologetic visibility in a city just beginning to recognize the people who had long lived in its shadows. Tom felt the shift in the air when he won. For the first time, someone like him, out, principled, unflinching, had a seat at the table. Milk didn’t just win office; he gave people permission to exist.

And then, less than a year after taking office, Harvey Milk was gone, murdered alongside Mayor George Moscone inside City Hall.

“Harvey gets elected,” Horn says softly, “and then Harvey gets killed.”

It was November 27, 1978. “I was in my office at 1701 Franklin Street. I had just finished meeting with a client. My secretary walked in and said, ‘The Mayor and Harvey have just been shot and killed.’”

Dan White, a former police officer and fellow Supervisor who had recently resigned, had slipped through a basement window at City Hall with a revolver. He murdered Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk with calculated cruelty.

“We were shell-shocked,” Tom says. “Everyone was.”

That night, the city gathered not in rage (not yet), but in sorrow. Somewhere between 25,000 and 30,000 people converged at the corner of Market and Castro. “We all gathered at the corner of Market and Castro and they gave us candles. I don't know where they all got their candles; it was the night and there's no wind. Very unusual. So the candles didn't blow out. 10s of thousands of people holding candles. And we walked from Market and Castro to City Hall. There's no violence, no police cars got burned. Nobody got arrested.”

Harvey Milk candle-lit vigil (November 27, 1978) / Courtesy of SF Musem and SF Gate

There, under the building’s great dome, Government Supervisors, including Carol Ruth Silver, addressed the crowd. The voices were steady, grief-thick, but composed. And then, something extraordinary happened.

“A group of men stepped onto the steps.”

No one announced them. They had rehearsed only once. There was no spotlight, only starlight and the golden glow of candles. They turned toward the crowd and began to sing. It wasn’t polished. It wasn’t pristine. It was better than that. They carried sorrow like a hymn, letting it swell, bend, and resolve through harmony. The sound moved through the vigil, like water through cracked stone—cleansing, rising, revealing.

At that moment, a new kind of aria was born. One not written for the stage but for the street. Not for applause but for healing. Music, at its most elemental, had arrived as a kind of mercy. Tom Horn stood with the crowd, engulfed.

“That was the inaugural performance of the Gay Men’s Chorus.” A month later, Jon Reed Sims officially formed the group.

“Dan White has been taken into custody. And he’s confessed. Everybody assumes that he will be convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life or the death penalty. Everybody just went home.

The Verdict and an Acronym

The jury had spoken, not with justice, but with leniency. Dan White had been found guilty of manslaughter. Not murder. The sentence? Seven years. He would serve five.

San Francisco’s gay and marginalized community, already battered by grief, rose in anguish. The White Night Riots ignited outside City Hall. Police cars blazed. Glass shattered. Rage poured into the streets, not because Milk had died, but because the system had excused it.

“I was watching it very closely on television. It was all being carried live. When I got the call from Gordon Armstrong, who was the chief trial lawyer, he was always corralling the gay lawyers, and he said ‘we've all got to get down to the courthouse at 9:00 tomorrow morning and represent all these guys. Because a bunch of them got arrested.’ So that was in my skill set, that I would do. At 8:00 the next morning. I’m down at the courthouse with all the other gay lawyers, and we’re representing all the guys that got taken into custody for various crimes related to the riot. We got them all off.” Horn says, not with bravado but with a kind of quiet pride for a job he was trained to do, for a tribe he came to live among.

They didn’t know it then, but that morning was something more than a crisis response. It was the beginning of what would become BALIF (Bay Area Lawyers for Individual Freedom), the first LGBTQIA+ bar association in the nation. Though Tom wouldn’t claim to be one of the official founders, he was there. Present. Trusted. Standing in the courtroom when it mattered. “I wasn’t trying to make history,” he reflects. He was trying to clean up after it.

Courtesy of https://www.balif.org/about

The Keeper of the City’s Stages

In 1981, Mayor Dianne Feinstein appointed Tom Horn to the Board of Trustees of the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center, a civic gesture that, in Horn’s words, “changed my life.” It was more than a seat at the table; it was a quiet mandate to serve as a bridge between City Hall and an LGBTQ+ community growing more visible yet still profoundly vulnerable.

“There were only three gay commissioners at the time,” Horn recalls. “And I thought, if I’m going to be the liaison, I need to know the gay press and its people.” So he picked up the phone and called Bob A. Ross.

Ross, co-founder and publisher of the Bay Area Reporter (B.A.R), had built more than a newspaper; he’d built a lifeline. “He hired incredibly qualified people who couldn’t get jobs in straight media,” Horn says. “Because they were gay.” The B.A.R became a cultural barometer, capturing the pulse of a community navigating grief, resistance, and proud emergence.

B.A.R. covers through the years, one from 1975; the 1989 issue after the earthquake; the 1996 opening of the Hormel Center at the San Francisco Public Library; the 2003 Supreme Court decision striking down sodomy laws; and same-sex marriage in San Francisco in 2004. Photos: Courtesy B.A.R. Archive

Their first lunch turned into a lasting friendship. “We both loved opera,” Horn says. “He had an encyclopedic knowledge of it.” When Ross’s longtime lawyer died of AIDS, he asked Horn to step in as general counsel for the paper. It wasn’t a public role, but it was pivotal. Another way for Tom to use his skill, not for power but for preservation.

Years later, as Ross neared the end of his life, he entrusted his philanthropic legacy, The Bob A Ross Foundation, to Horn. “Give to what I give to,” he told him. Tom has honored that promise with quiet fidelity.

Ross gave to San Francisco Opera, notably the Merola Opera Program. “He loved it,” Horn says. They didn’t attend performances together; Ross preferred Tuesday nights “with the swells,” Horn laughs. “But I had work in the morning. I went on Saturdays.”

So when the Opera’s development office approached Tom over lunch to discuss something new, a full-scale Pride concert, he said yes without pause. “Bob would be supportive. I’m supportive,” he said. That’s always been the mark of Tom Horn’s philanthropy: principled, immediate, personal.

“I didn’t realize this was the Opera’s first official Pride concert,” he admits. “They used to do ‘Out at the Opera’ nights, and we supported those. But this… this is something bigger.”

Indeed it is. On June 27, the War Memorial Opera House opens its doors to a landmark event, queer artistry taking center stage in one of San Francisco’s most venerable cultural institutions. With world-class performances, immersive visuals, and a post-show dance party, the evening promises to cast the Opera House as a vessel of transformation.

BUY TICKETS FOR SF OPERA'S PRIDE CONCERT

Caesar and the Space for Love

If the city was Tom’s public romance, Caesar Alexzander was the private one. Caesar had strong hands and an eye for balancing light and composition. They met 35 years ago, navigating plagues, propositions, and presidencies together. “He grounds me,” Tom says.

Thomas Horn and Caesar Alexzander. 1. SF Social Event; 2. Monaco 3. Christmas Card / Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Horn

Decades after they first met, in 2018, they made the big decision.“I called Gavin [then-Lieutenant Governor Newsom] on his cell phone. He was running for Governor. It was Monday. I said, ‘You know, we need to get married. We want you to officiate it. We can do it anytime at your convenience.” Newsom responded quickly, “How about Friday at 4:00?”

“Friday is the most popular day for weddings at City Hall. It was completely booked,” Horn continues. “I don’t remember why, but we were sitting and talking with [Mayor] Ed Lee and I'm telling him we were leaving. ‘Oh just do it in my office.’ he said.’” So they did, in the International Room, where the Mayor hosts foreign dignitaries and guests.

“I don't know, after all those years, to be in a society that you were told you can't marry who you love…to finally be able to marry. It was a good day.”

Thomas Horn, Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom, Caesar Alexzander at City Hall (2018) / Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Horn

Pride Month

Tom Horn turned 79 this month. He and Caesar celebrated quietly with an art exhibition at de Young’s Bouquet to Art, a walk through Twin Peaks, and a steak at his favorite restaurant that shall not be named. The Pride Concert is around the corner. Horn will walk into the War Memorial Opera House like a man entering both a cathedral and a battlefield. The chandeliers blink on. The overture swells. He will recall his favorite opera, Tosca (performed at the War Memorial in 1978), where he was mesmerized by Pavarotti and Montserrat Caballé. He didn’t know then but heard later that Harvey Milk was in the same audience a week before his assassination. All the memories connect.

And he knows:

Not every revolution needs a soundtrack. Some, like his, are carried out in minor keys, behind podiums, in courtroom halls, in ink-stained newsrooms, and the Opera House. They don’t erupt. They endure.

When he steps back out into the San Francisco night, past colonnades and applause, into a city now pulsing with music and joy, he will see them: people celebrating not just the Pride Concert but the freedom to exist.

He draws a breath.

And in that quiet exhale, San Francisco breathes a little easier because of him.

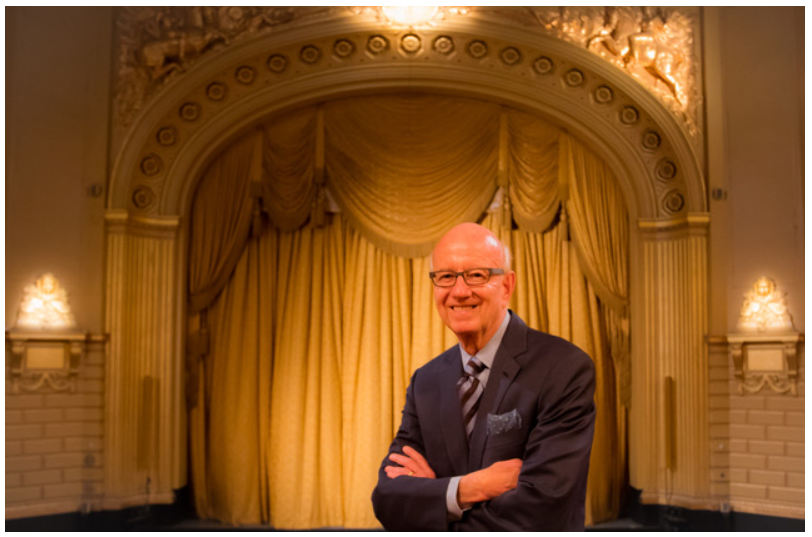

Thomas Horn in War Memorial Opera House / Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Horn