San Francisco Opera Celebrates AAPI Heritage: Four Artists Redefining Opera’s Narrative

Huang Ruo

Huang Ruo, born off the southern coast of China the year the Cultural Revolution ended, is a U.S. citizen long admired for his genre-defying fusion of Chinese folk, Euro-classical, and avant-garde music. Huang's father, a well-known composer and composition teacher, started Huang’s piano lessons at six years old. Huang tells the story of a recital that he performed: When he forgot part of his Bach selection, he remembered his teacher telling him to improvise in such a case. “Afterward,” said Huang, “my piano teacher told my father that she didn’t think his son was going to be a pianist, but he might be able to write music.”

When Huang was 12 years old, his father enrolled him in the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. There, he learned both Chinese and Western music. At 20, he won the Henry Mancini Award at a festival in Switzerland. He then went to the United States to study at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio and The Juilliard School in New York City. He studied composition and earned a doctorate.

His compositions act as vibrant cultural bridges, echoing ancient stories through experimental soundscapes. They are also tools that take opera from a Eurocentric influence and give Asian narratives an authoritative and uncompromised stage. His operas Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (2011), An American Soldier (2014), Paradise Interrupted (2015), and M. Butterfly (2022) recentered voices silenced by racism and erasure.

Butterfly was the first play Huang saw in America. He thought the title was a misspelling. “I saw several versions of the play, and I often felt it needed to be told in musical form because it was so related to Puccini and to the reversal of Madama Butterfly. I felt, in opera, I could freely integrate — to twist and to turn, To create all the drama with the music,” Huang said in an interview with Javier C. Hernández of The New York Times.

In M. Butterfly (2022) Huang upends Puccini’s orientalist tropes in Madame Butterfly with a composition that features driving rhythms balanced by moments of lyrical calm, blending vivid textures with traditional harmonic foundations. The composition integrates Western instruments with percussive elements drawn from Chinese tradition. This fusion creates a dynamic interplay between cultural influences anchored by the rhythmic patterns evoked by play.

“There are so many stories, good topics, and subjects, but I also feel as an Asian American I have a duty to write about stories that are more relevant to my background, my culture,” Huang stated in an interview with the National Endowment for the Arts.

In his compositions, Huang conveys a yearning for a bygone culture by infusing Asian sonic aesthetics into a form traditionally used to exoticize them. This fusion integrates 5,000-year-old Asian traditions with 400-year-old European definitions. The result is a multidimensional approach to composition that explores how music can reunite Asian Americans with their eroded heritage.

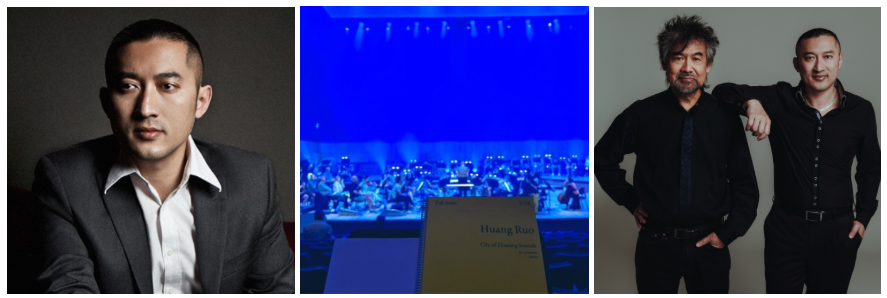

1. Huang Ruo (2015) / Photo: Ricordi 2. Rehearsals of City Of Floating Sounds「浮聲之城] with BBC Concert Orchestra (2025) / Courtesy of Huang Ruo 3. David Henry Hwang and Huang Ruo, An American Soldier (2018) / Photo: Matthew Murphy

David Henry Hwang

If Huang Ruo transforms reclamation into music, David Henry Hwang crafts its narrative. Hwang unearths stories obscured by centuries of cultural misrepresentation using playwriting to cultivate Asian American consciousness on stage.

David Henry Hwang was born into the fabric of the American Dream. His parents were successful and ensured that all three of their children had excellent education and opportunities. His father, Henry Yuan Hwang, was born in Shanghai. He received his BA in Political Science from Taiwan University. At 21, he left China as Communists prepared to take over. He relocated to Linfield College, Oregon, earning a second bachelor's degree in Political Science. And then went on to study accounting at the University of Southern California, where he met his wife, Dorothy. Henry Yuan Hwang founded the first Asian American-owned federally chartered bank in the United States and President Reagan appointed him to the White House Advisory Committee on Trade Negotiations.

David’s mother, Dorothy Hwang, was born in China and attended boarding school in Manila to study piano. When the time came for college, she decided on the warmth of Southern California, earning both her Bachelor's and Master's degrees in Music at USC. Dorothy later began teaching the piano privately and joined the faculty of the USC Preparatory Division, which became the Colburn School of the Performing Arts, where she continued as a Master Teacher.

David Henry Hwang entered Stanford University intending to become a lawyer. That all changed when he took a playwriting class in his freshman year, sparking the desire to become a playwright. With the same analytical skills and robust educational background it would take to be a lawyer, Hwang turned his attention to playwriting, which, at the time, was not a major at Stanford. He changed this for himself and graduated with a playwright major in Stanford’s Creative Writing Program. It was a bold act he employs today: Changing the narrative in an established dialogue.

Acknowledged as the Henry Miller of his generation (TIME 1989), Hwang produced over 40 bodies of work including plays, musicals, TV series, and operas. His best-known work, M. Butterfly (1988 Tony Award), propelled him into America’s consciousness. Inspired by Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, this story interrogates Orientalist fantasies and Western projections. His path of stripping away the characterization of the Asian American misconstrued narrative began as a senior at Stanford with FOB (1981 OBIE Award), which depicts the contrast and conflicts between established Asian Americans and “fresh off the boat” (FOB) newcomer immigrants.

Growing up in the shadow of his accomplished patriotic parents, Hwang initially embraced cultural assimilation and dismissed his heritage as peripheral to his identity. Early in his academic journey, he struggled to find his narrative voice; however, as his writing evolved, his subconscious gravitated toward themes of cultural dissonance, reshaping his perspective. This shift led him through self-described phases of “Isolationist nationalism” before settling into a nuanced, multicultural ethos rooted in the complexities of belonging.

This journey forms the basis of his artistic approach. Instead of crafting a moral lesson, he invited audiences to grapple with the layered contradictions in his stories. In M. Butterfly, he juxtaposes binaries like East and West or gender roles. Whereas, An American Soldier tells the story of patriotism gone wrong and deliberately withholds a resolution, prioritizing ambiguity over closure. Hwang transforms storytelling into a collaborative act of reflection, urging viewers to confront the tensions between cultural inheritance and self-definition.

Hwang’s voice has reached heights that will be studied long after his chapter is concluded. He is a Tony Award winner and three-time nominee, a three-time OBIE Award winner, and a three-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He is the most produced living American opera librettist, and his works have been honored with two Grammy Awards. He co-wrote the Gold Record “Solo” with the late music icon Prince, wrote the NBC miniseries The Monkey King (The Lost Empire), and was a writer/consulting producer for the Golden Globe-winning television series, The Affair.

Even so, it is not Hwang’s awards that bring him the most satisfaction; it is his consistent ability to shatter preconceived ideas of what it means to be Asian American, leading audiences to confront the stereotypes they consume. Hwang redefines how Asian stories are told on stage by challenging notions of race, gender, and nationality, making his audience ask the question: How did it really happen? Hwang investigates what it means to be American. He asks, “Who gets to be American? Whose American identity is assumed, and who has to prove it?”

Hwang's questioning doesn’t stop at the script. As Chair of the American Theatre Wing, he pushes for representation in leadership, funding, and education. He excels on the predominantly white stage and is changing the theater institution from within.

As scholar M. Johnson notes, Hwang’s adaptations embody the “diasporic tension between preserving ancestral memory and reimagining it for transnational circulation.” Theater, often perceived as a Eurocentric art form, becomes, in Hwang’s hands, a space for an ongoing exchange and understanding between different cultures and perspectives, one where Asian characters are neither exoticized nor reduced to stereotypes but rendered with authentic humanity.

1. David Henry Hwang (2025) / Courtesy of David Henry Hwang 2. David Henry Hwang with Stan Lai at Dream of the Red Chamber opening (2016-2017) / Photo: Drew Altizer 3. David Henry Hwang and Huang Ruo, The Monkey King panel discussion / Photo: Work and Process, Guggenheim

Carolyn Kuan

In 2011, Carolyn Kuan became the first woman and Asian American musical director at Hartford Symphony Orchestra. Kuan earned a Master of Music degree at the Peabody Conservatory. She won the first Taki Concordia Fellowship (2002) and was the first woman to receive the Herbert von Karajan Conducting Fellowship (2003), which led to a residency at the Salzburg Festival. Her career includes working as a conducting assistant to Marin Alsop and collaborating on numerous operatic projects with Huang Ruo and David Henry Hwang, including Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, An American Soldier, and the UK premiere of M. Butterfly.

To understand how Maestro Kuan accomplished so much, we must return to Taiwan when she was 14 years old. During a visit to her middle school’s sister school, Northfield Mount Hermon in Massachusetts, an American teacher told the students, “Feel free to ask any questions.” This was the moment that changed Kuan’s life. Kuan said that she fell in love with the education system in the United States. “In Taiwan, the education system is very much memorization,” said Kuan. “You were told what you were supposed to know and then tested on what you were supposed to know. I remember that summer we were encouraged to ask questions and argue with the teacher, and I'm rebellious. A light bulb went on. This was how I wanted to study and learn.”

Behind her parents’ backs, she applied for a scholarship to study in Northfield. When she won, she convinced her parents to let her go, expecting her to have a career in investment banking. With a rebellious spirit and insatiable curiosity, she traveled to the United States alone, knowing little English. Upon arrival, Kuan followed an endless series of questions, “Why do we do what we do?” The more she learned, the deeper the music grew within her. Her drive was simple but profound: the desire to make a difference, but it was not in music; it was with music; and how it could be a catalyst in creating a community. For Kuan, conducting classical music found her more than she found it. “It was an organic process,” said Kuan.

With the Hartford Board, Kuan embarked on a shared journey: one built on her skills and was achieved through a relentless work ethic and fearless imagination. She continually asked herself, “How do we connect with the community?” The answer she found was radical in its simplicity: “By giving space,” said Kuan. She sees the audience not as spectators but as collaborators in the musical experience. "Music is a conversation about the human condition and culture, history, and language," Kuan later said in an interview with Catherine Shen of Connecticut Public Radio. This philosophy shaped her every step.

Kuan views music as a counterweight to the world's chaos, a meditative process built one note at a time. She believes that music offers a sacred pause; a place where people can find reflection, shared consciousness, and healing; and a place where the audience becomes an inclusive community without barriers. Her programs often have experimental formats and bold political and social themes. She works knowing that diversity is not achieved by accident; it must be cultivated intentionally. She is an advocate for opportunities given to those who might otherwise be overlooked, ensuring that stages and audiences reflect the full breadth of the human experience.

Through her leadership, Kuan challenges the classical world by reimagining what excellence looks like. Above all, she believes in the power of shared experiences. In her hands, a symphony is not a relic of the past; it is an active call for unity, gratitude, and consciousness. "There’s a lot of good in the world," she says, "And music reminds us to find it, to feel it, and to share it."

1. Carolyn Kuan / Photo: Charlie-Schuck 2. Carolyn Kuan and Huang Ruo / Photo: Asian Society 3. Carolyn Kuan conducting the 2011 Talco Mountain Music Festival / Photo: Steven Laschever

Anita Yavich

In theater, where every element must harmonize to create an otherworldly experience, costume design is a pivotal tool in storytelling. At the forefront of this art form is Anita Yavich, a visionary whose work exemplifies a blend of aesthetic and cultural references. Her designs are dynamic tools that push the boundaries of what is possible while honoring the richness of diverse cultures. Yavich’s contributions offer a profound exploration of innovation, cultural identity, and the influence of artistic expression.

Born in Hong Kong during its time as a British colony, Yavich experienced Eastern and Western influences. She witnessed firsthand Hong Kong’s political complexities, which resulted in protests, tear gas incidents, and news of friends’ and neighbors’ arrests. At age 13, Yavich and her father relocated to Nigeria, where she was the only non-African student in her new school, in stark contrast to her colonial schooling in Hong Kong. Yavich’s father transferred her to an American International School until she reached high school when they moved to San Clemente, California. These transitions made her feel like an outsider. However, with the support of her public high school, her creativity was encouraged. "The teacher was like, 'Hey, what do you think?'… No one had ever wanted to know what I thought," said Yavich.

Growing up across three continents, Yavich questioned her sense of belonging. She recalled, “I didn’t know what kind of Chinese I was,” during that time. This quest for belonging as a global citizen has informed her design approach, in which she often blends diverse cultural elements to create something entirely new.

In Golden Child (1998), written by David Henry Hwang, Yavich used Chinese floral symbolism–peonies for excess and cherry blossoms for fragility–to comment on foot-binding and patriarchal polygamy. She hand-painted costumes that mirrored women’s resilience in male-dominated societies. In the opera Facing Goya (2000), Yavich combined gargoyle motifs with lab coats, observing how art and science often erased non-Western contributions. In San Francisco’s opera Aida (2016-17), Yavich reinvents the time-tested story with nontraditional colors and fabric transparency, making a statement on hierarchy and power.

All her works echo the disdain of colonial exploitation. Her work challenges power structures by blending techniques, materials, and symbols that mirror marginalized cultures. “I want the costumes to ask, ‘Who gets to be remembered?’” said Yavich.

Anita Yavich’s career as a costume designer, whether for plays, puppets, or opera, is a testament to her multicultural upbringing, the transformative power of art, and the enduring impact of different heritages coming together. Her designs go beyond costumes; they are worlds within the folds of the fabric.

1. “Aida costume sketches of women in chorus (2016-17) / San Francisco Opera archives 2. Anita Yavich / Photo: Tyrone Turner WAMU 3. The Monkey King sketches (2025) / San Francisco Opera collection

1. “Aida costume sketches of women in chorus (2016-17) / San Francisco Opera archives 2. Anita Yavich / Photo: Tyrone Turner WAMU 3. The Monkey King sketches (2025) / San Francisco Opera collection