Backstage with Matthew: To pronate or to supinate?

As Fight Director, Dave works with us on any show that includes any kind of simulated physical violence. This can be as small as a slap onstage, all the way to the huge fight scene of Die Walküre when Hunding kills Siegmund – one of the largest fights that Dave has set on our stage, replete with hunting dogs and weaponry. Dave specializes in taking dangerous situations and making them safe onstage while ensuring they remain compelling to the audience. He astutely notes that violence onstage can allow us to engage in dialogue about its place in the world without anyone getting hurt.

Romeo and Juliet as a title is rife for rapiers: last season alone, Dave fight directed five spoken theater productions of Romeo and Juliet across the Bay Area, and next season will be his 4th Romeo and Juliet for Cal Shakes. Dave notes that operatic Romeos tend to be shorter on the fight sequences, but he appreciates being able to set a fight to music in opera. Having a score helps to create definition and shape to the fight sequences.

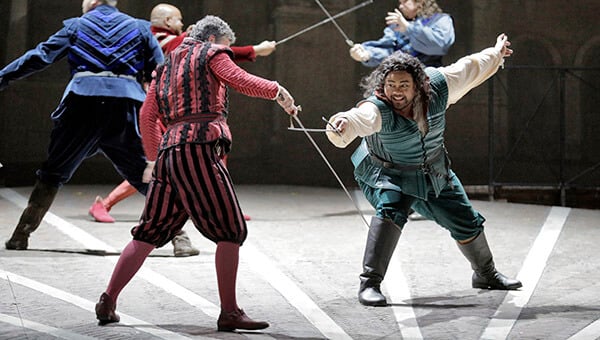

Our Romeo and Juliet calls for a number of fast paced fight sequences in the third act and the scene in which Tybalt kills Mercutio, and Romeo responds in kind, killing Tybalt. It is an intense fight sequence with many swords drawn onstage and it has to be carefully set and worked out with the cast and the chorus.

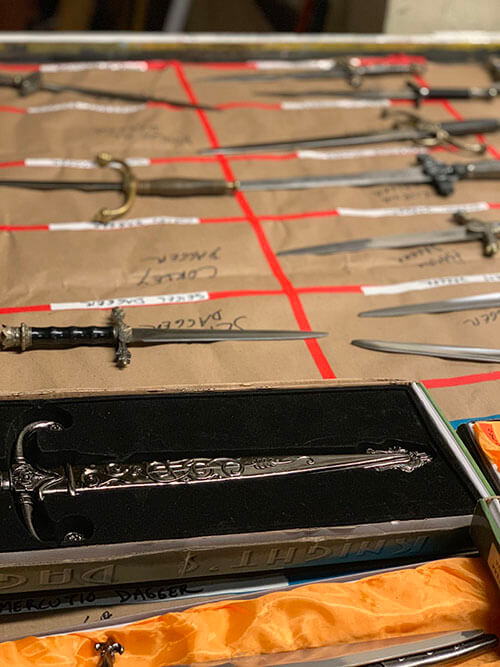

Dave begins by discussing the choice of weapons with the SFO props department. You may recall my very first Backstage with Matthew was with Scott Barringer, our Master Armorer. Dave and Scott work very closely together to select the weapons used onstage. For this production, they selected a schlager bladed rapier, as opposed to an epee blade. The schlager, with its broader blade, is more historically accurate for this period in Renaissance Verona – the epee had not yet been developed.

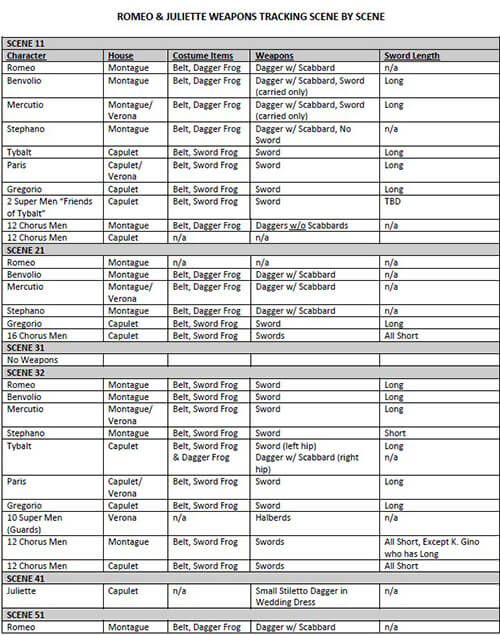

Dave and Scott also worked together to pick the daggers that are used throughout the show, including the dagger used by Juliet. As you can see, the detailing is very unique to each dagger and we keep a very clear track of which people onstage have which weapons.

In fact, the weapons in this opera have their own tracking sheet that ensures that stage management, props and other departments have a very clear set of details on where weapons are at any point.

Once weapons were selected, Dave began the staging process with a three-hour rehearsal with the chorus, and told me how enthusiastic they were to be working on a sequence like this. Many artists have theatrical sword training in their background and, while they may carry many swords onstage, they rarely get to use them in combat onstage. Although this production came to us from Monte Carlo and Genoa, the archival video that helps guide things like fight sequences was dark and hard to make out the specifics of the sequence. So Dave was able to create much of the fight work from scratch, working with the director Jean-Louis Grinda.

When working with artists, Dave notes that there are some standardized rules of stage combat, most importantly centered around how to evade an aggression. The most important thing to ensure safety in a fight is to have the recipient of each fight move be in complete control of their reaction, and Dave taught me a five-step process that is standard for every fight sequence, whether with a weapon or with bare hands:

- Eye contact. The artists lock eyes and use them to communicate intent.

- The Cue. The aggressor will give some known visual cue to the recipient, e.g. a raised arm, a drawn sword, that basically triggers the fight sequence.

- The Evade (or Duck). The receiving artist has learned when and how to duck out of the way to make way for…

- The Attack. Now the attacker can go in for the attack, but safely knowing that the recipient of the fight has already ducked out of the way.

- The Recovery. The artists re-stablish themselves and prepare for the next step in the fight.

Dave is one of only six Master Fight Directors with Dueling Arts International, a level he attained last year after working up the ranks from apprentice to associate to a full fight director, then to senior fight director, and finally to the master level. He is one of the few people in America to be making a full-time career out of fight direction and he works with many of the Bay Area theater companies, as well as teaching at Berkeley Rep and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. His own background is as an actor, training at NYU’s experimental theater program. He found himself always cast as a cop, soldier or criminal – he was always beating someone up on stage, or taking a beating, so he decided to learn how to do it properly and safely. A move to San Francisco introduced him to Gregory Hoffmann, who mentored Dave, and taught him how to create the illusion of violence onstage.

Dave works in all manner of fight contexts. Most of his work is non-weaponry, with much being staging domestic violence sequences onstage (we had examples in Two Women back in 2015). But he also specializes in all forms of weaponry and martial arts (he stresses he’s trained in the art of how to give the illusion of these forms of combat, not the combat itself, although a strong knowledge is required). He recently worked on a play for Cal Shakes which included sequences of Indian staff fighting. This ancient combat art was new to Dave, but through research and taking lessons he developed an onstage language for how to have actors effectively portray this form of martial arts.

Safety and believability are two integral parts of any fight work, and Dave leads brush-ups of the fight sequences onstage during each performance. For every fight scene, we want to ensure it’s in the hands and heads of the artists just before they have to do it onstage. These are images of Pene Pati and Daniel Montenegro brushing up the fight sequence with Dave during the intermission of Romeo and Juliet’s dress rehearsal.

But back to the title of this Backstage with Matthew – to pronate or to supinate. This refers to the orientation of the sword in the hand, and speaks to the level of detail that Dave brings to his artistry. Italianate sword work of this time required one to pronate – to keep the palm face down – and you should see all of the swordwork on stage in Romeo and Juliet being pronated, creating a historical authenticity. The French, however, used supinated sword positions – with the palms up. While the Italians and, to a lesser degree the French, would travel Europe training the nobility, Dave notes that the Spanish methodology wasn’t available to be taught in Renaissance Europe. The only way to learn the Spanish technique was to go to Spain and fight a Spaniard!

Top: Pronation and Bottom: Supination – two different historically accurate approaches.

Ultimately safety is the main focus in any onstage fight sequence, and Dave gives the artists latitude to do what makes them feel comfortable and safe. But in the choice of weapons, the stylistic approaches, and the techniques of combat, Dave brings immense knowledge, wisdom and artistry to our fight sequences, ensuring that those parries and thrusts onstage are as believable as possible without ever putting an artist in harm.

Dave has been our Fight Director since 2012, and we are so fortunate to have such an expert right here in the Bay Area, keeping our artists safe, while also keeping our audiences on the edges of their seats!