Backstage with Matthew: A dash of holiday magic

My guide through the magical world of Hansel and Gretel was Erik Walstad. Erik is our Technical & Safety Director at San Francisco Opera, overseeing the smooth and safe functioning of the stage. Erik was involved in Hansel and Gretel before it was even built, working with our colleagues at the Royal Opera House to ensure that this co-production could work seamlessly here in San Francisco. As the production moved here after its London premiere, he and the rest of our technical team ensured that all of the details came to life perfectly, working with members of our stage crew to create a magical experience for the audience. In what was a pretty fabulous backstage tour, Erik showed me around some of the tricks that I didn’t want to unveil before you’d had a chance to see the production!

We started with the magic spoons. If you recall, every time a spell was cast on stage, a wooden spoon came to life with flickering lights before shooting out real flame! How to make a wooden spoon into a pyrotechnic marvel? This all came to life in the hands of Geoff Heron, our pyrotechnic expert on the stage crew, who crafted these particular spoons.

The spoons are made from an aluminum frame, then taped up and painted to look like real wood. The spoons contain two pieces of technology, both controlled by buttons on the handle. The flickering lights come from LEDs built into the bowl of the spoon and operated by a microchip programmed by electrician Paul Puppo on our crew. The flame-throwing aspect comes from another button, but one that requires the flickering LEDs to be activated first. That creates a safety feature called a “dead man switch” – a double activation, further made safe by requiring the flame switch to be pushed twice in succession by the operator (either the witch, Hansel or Gretel). So you depress the LED switch, then activate the firing mechanism then press again to fire!

The flame comes from two scrunched up pieces of flash paper – very thin paper coated with nitrocellulose and an oxidizing agent. Flash paper burns very quickly and at great heat – disappearing in a matter of milliseconds. There is no way that it could ever reach the floor while still on fire – the combustion is far too quick. But how to get it to throw a flame? That’s where the two pieces of flash paper come in. Geoff packs both into a small red holder which contains an electronic ‘match’. The match ignites the first piece of paper and that piece of paper ignites the second, propelling it out of the spoon! The spoon is testament to Geoff’s incredible pyrotechnic skills and it made for a magical addition to the witch’s scene!

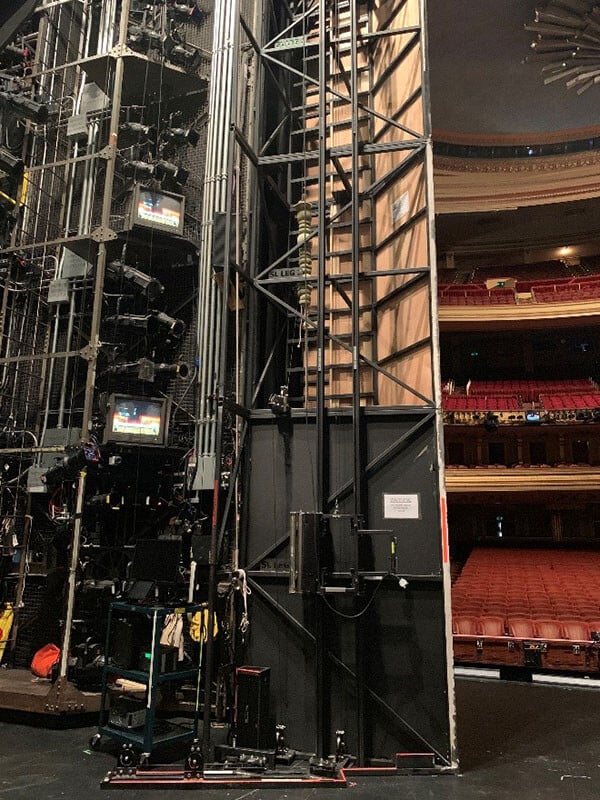

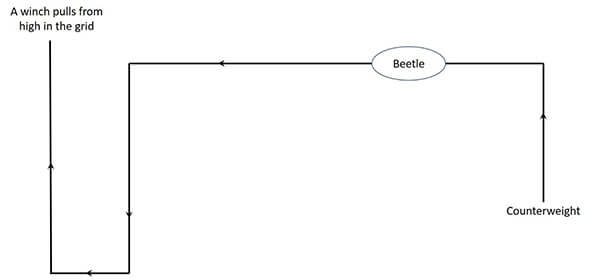

Erik then took me to the back of the false proscenium – the wooden surround to the whole production that contained the cuckoo clock. As you may recall, during the second act in the woods, two little bugs slowly inched their way around this fake proscenium – a glowing moth on the house right side, and then a beetle across the top behind the cuckoo clock.

The beetle is pre-set before the performance starts, but the moth gets placed during the scene change going into Act II. How do they travel so slowly and effortlessly? Well, it turns out both are on clever pulley systems hidden in that false proscenium.

The moth – lit by LED tape that makes it glow – has a relatively simple vertical pulley system. The beetle has a more complex path that goes up one side of the backstage, across the top, and down to a counterweight on the other side. Moving the beetle is not just about tracking it across, but ensuring it can return to its original place, to be reset for the next night. So a counterweight is added to one end of the beetle, allowing it to be moved in both directions! That simple looking false proscenium hides a lot of magic!

Then, it’s onto the witch’s house and the chocolate pot! A fabulous creation by the Royal Opera House. The house itself is moved by two operators – here Dave Herron and Roger Lambert, standing behind the house and moving it using two built-in motors that allow it to move downstage and turn.

There are two big effects with the chocolate pot: first the sinking of the witch as she descends into the gooey chocolate inside. This is accomplished with a lift built into the pot. The witch is pushed out onto a squishy, foam lid made to look like chocolate and then the lift descends taking the witch and lid down together. Of course, I had to test this out – it gives one of the most unique views of the opera house chandelier that I’ve ever had!

The second effect is the crashing open of the chocolate pot when the witch dies. A huge explosion accompanies a break-away piece of the pot crashing down, revealing the witch covered in chocolate (a herculean costume change that Robert Brubaker, our witch, had to do on his own within the chocolate pot!).

The explosion comes from two charges on either side of the chocolate pot, fired remotely by Geoff Heron, sitting offstage. The breakaway front then is released by two very strong inverse magnets. Their natural state is “on” when there is no power running to them, but when they are powered, they release and the front comes crashing down in a spring-loaded mechanism that makes it bounce a few times!

A bonus effect in the oven the creation of the steam – there is both steam in the bottom oven when the witch opens it, and steam coming out of the top of the pot. This is a very clever water vapor system that switches between the two uses, the switch effect again designed by Paul Puppo. The tank that makes the water vapor has a double exit path for the hoses – one to the oven and one to the pot. The switch can be wirelessly operated, closing off one system and opening up the other, thus saving on having two systems.

Then, finally, one rather traditional but still very effective piece of magic. The rocking chair – if you recall – magically moves across the stage as the witch traps Hansel. No complicated electronics here – this is some good old-fashioned theatre trickery! A black pad is pre-placed onstage attached to a very thin wire. The pad itself has a spike mark (the colored tape marks onstage that show where things need to be placed), and when Robert Brubaker, the witch, moves the chair onto the floor, he places it onto the pad. Mark Kotschnig on the props crew, is hidden away in the wings and, at the appointed moment, he pulls the wire across the stage, taking the chair with it! And then, once Hansel is in the chair, Sasha Cooke (playing Hansel) cunningly flips over the cross bar using a little metal lever, unseen by the audience, making it look like the chair is automated.

Productions like Hansel & Gretel are full of intricate stage techniques that require extraordinary skill to engineer and operate. Even in a coproduction like this that is built elsewhere, the magic techniques themselves are often designed locally at each venue based on what pyrotechnics are allowed and which systems are in place in the theater. The seamless operation of magical moments like these is a great testament to the skills of our stage crew and technical team, headed by Erik – they are a group of very talented people committed to ensuring the very best experience for our audiences.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this little under-the-hood look at the magic in Hansel and Gretel and that you’ve enjoyed this year of backstage glimpses. I’m so proud to be working alongside so many talented people in so many different disciplines, and it’s a pleasure to share their stories with you.

I wish you a joyful holiday season and look forward to sharing more thrilling opera with you in 2020.