Backstage with Matthew: Working Out the Wings

The role of angels in this opera is very significant: not only is Clara on a quest to earn her wings, but we also meet a quartet of angels who support Clara through that quest. Inspired by the concept of earning your wings through acts of kindness, we have created a community program with our great partners at Community Housing Partnerships and Compass Family Services. We’re calling this our “Earn Your Wings” program, and we’re encouraging our audiences to connect with these two vital organizations in San Francisco and help exemplify the importance of community connections, particularly during the holidays. I hope you will join the San Francisco Opera family as we enrich our own holiday celebrations by helping others.

But today I am writing not about metaphorical wings, but about the physical wings we are using in this production. Wings are an important part of the story-telling in this piece, and so I thought it would be interesting to delve into how the wings were made and how they operate through the production. This production originated at Houston Grand Opera in 2016, and it was the talented women and men of the HGO costume and props departments who created these wings. As part of the co-commissioning consortium, we then receive the wings here and adapt them for use with our house. (By the way, I’m very happy to report that HGO is now back home in the Wortham Theater after an entire year out of the building following devastating flood damage from Hurricane Harvey. Their basement is still under reconstruction, but the upper levels are thankfully now usable.)

The angel wings have both mechanical features and need to be secure for flying, so they are overseen by the prop department at the Opera, not the costume department as one might think. The collaboration is still strong, however, and when I was down on stage the props and costume departments were discussing fabric coverings for the wing harness to match the costume pieces. The wings are an excellent example of how interconnected we are as a company – costume, props, grips (for the flying), staging and technical staff, and artists working in a delicate interplay.

Each of the quartet of angels (all played by Adler Fellows) has two sets of wings. One set includes the mechanics for flying, and one set is just the wings. The mechanical wings have much more weight to them, and become heavy when worn for long periods. So after the angels descend to the ground and leave the stage, they return with a much lighter set of wings on. The harnesses are cleverly designed such that each set of wings can be bolted on and off quickly, ensuring safety but allowing for a quick change.

Dylan Maxson, started with our props crew in 1998, and is overseeing the wings for It’s a Wonderful Life. He helped explain the mechanics and fabrication to me.

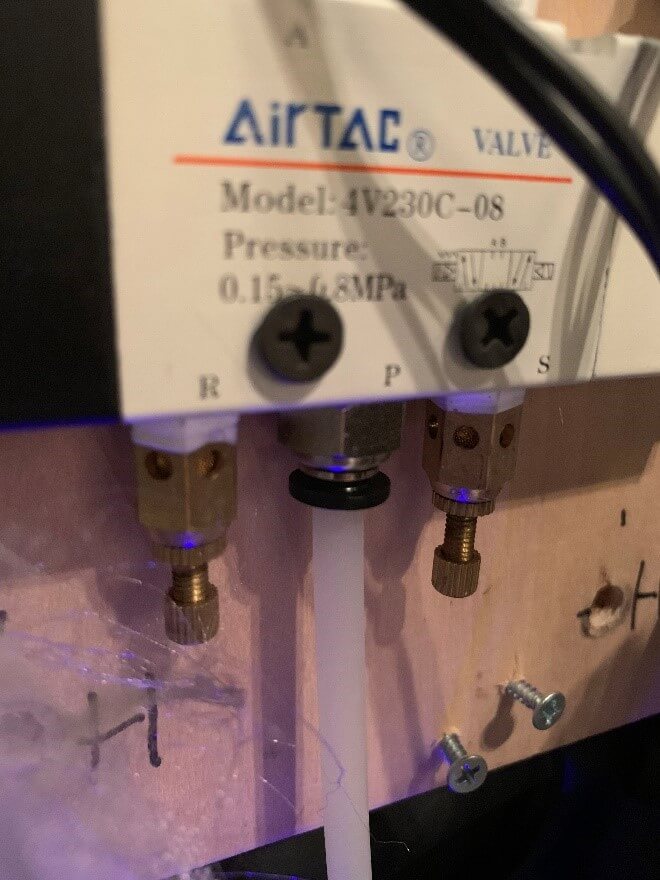

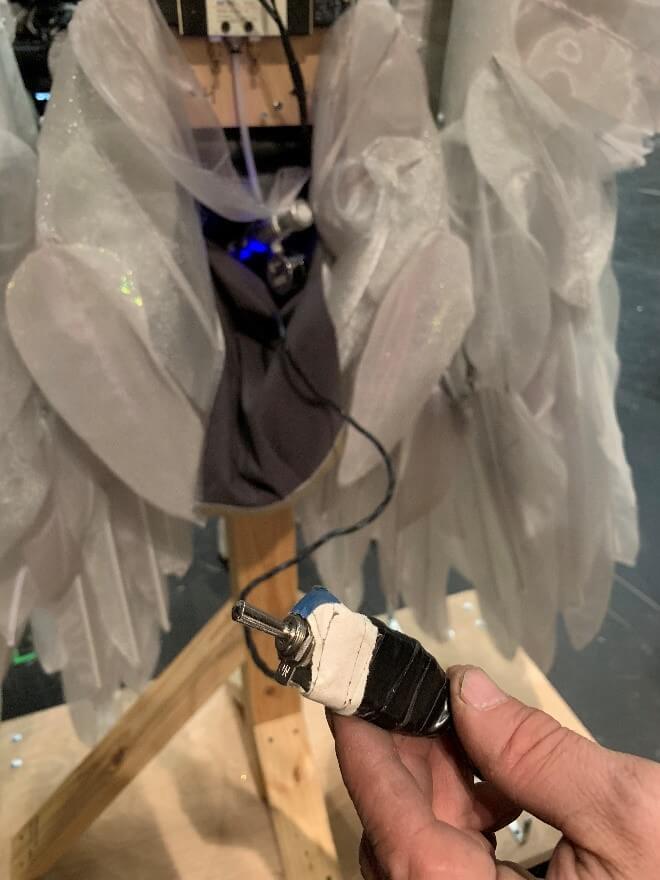

The mechanical sets of wings have to open and close, and this is done through a small pneumatic system. On the picture below you’re seeing a pneumatic valve operated by electronic solenoids. Once activated by a user switch, the solenoids open and close a pneumatic ram fed by a small canister of carbon dioxide. The pneumatic ram is built into the infrastructure of the wing and pushes out the infrastructure of hinges that unfurls the wings. To close the wings, you reverse the air flow and the wings contract. A small ‘gizmo’ changes the speed at which the air is exhausted, thus allowing Dylan to fine-tune the speed at which the wing retracts. You can see Dylan demonstrating the wing operation and the internal structure in this little video here:

The wings are built on regular safety harnesses, which are then hooked up to the rigging wires for flying. With one set of wings, however, Dylan made an intriguing new version. He used a regular hiking backpack with a waist strap as the core body of the harness, creating a much more comfortable structure. To allow the wings to be quickly mounted, he added plastic whaleboning to the straps of the bag, so that they are always popped out, ensuring that the artist doesn’t have to fumble to find the straps in the midst of quick change. It’s a fantastic solution!

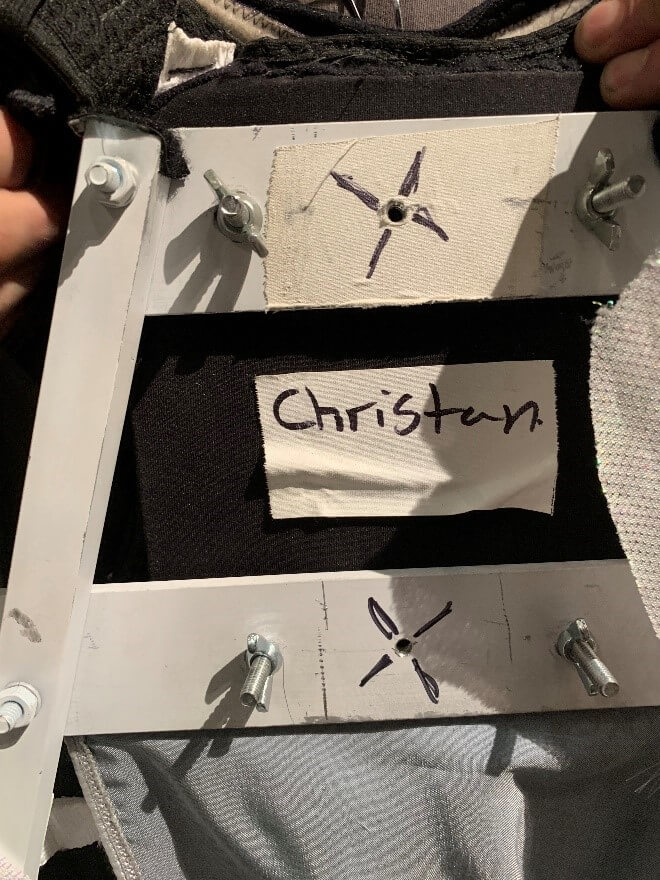

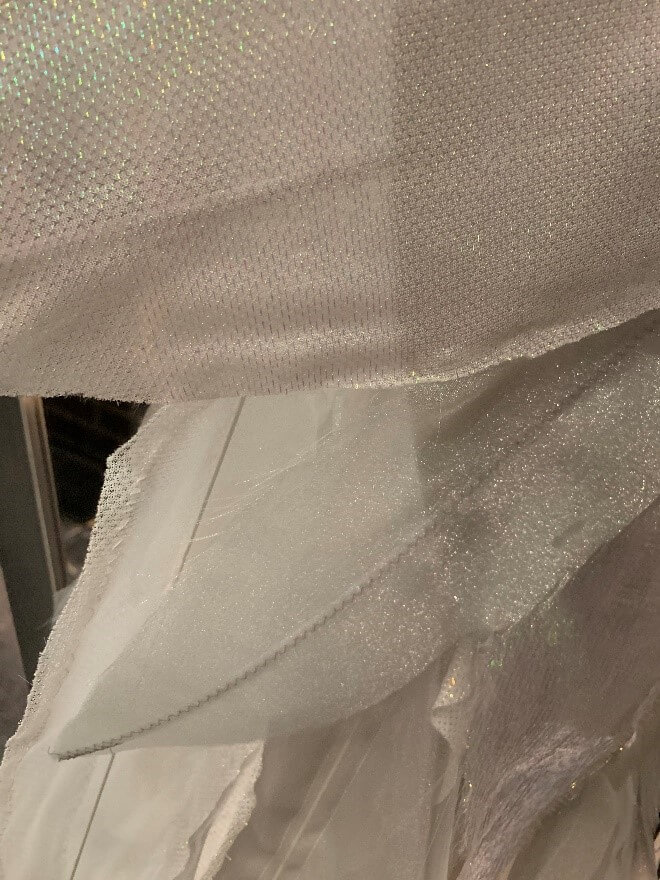

The wings themselves are made out of a few different fabrics to give a sense of texture. On the surface, each set of wings is identical; it’s just the question of whether they have the mechanism or not. Each double-pair of wings (mechanical + regular) is moved around on a custom-built cart, named for each singer and festively decorated by the Houston Grand Opera props department!

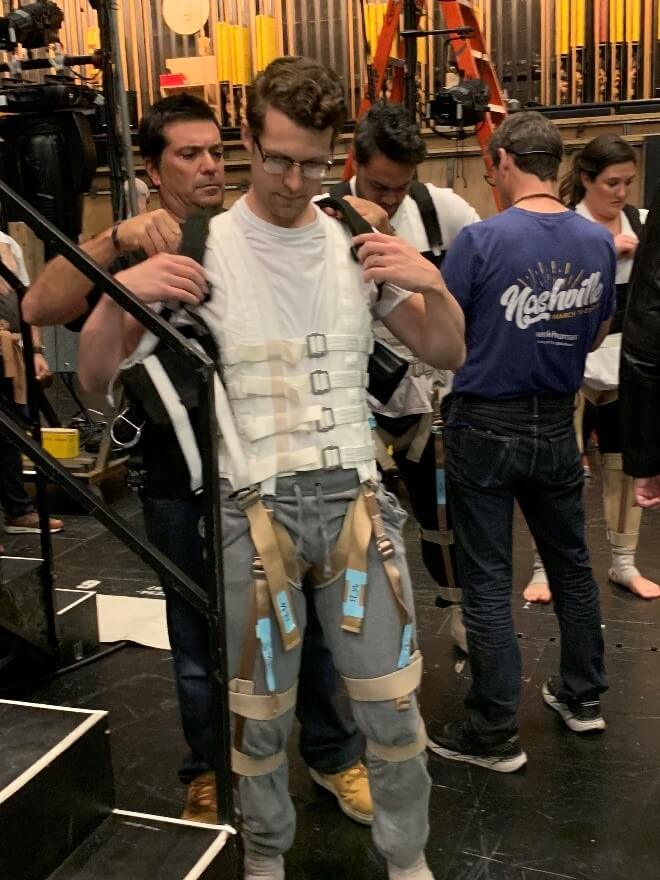

While I was down on stage, a flying technical rehearsal was under way, with the Adler Fellows getting used to their harnesses and the feel and functioning of the wings. As you’ll see in the photo below, highly trained members of the grips crew (also known as the carpentry crew), work with the singers to prepare the harnesses and get them comfortable with wearing the wings and then flying. Each of the angels has a spotter (or “wing-man”) up on a walkway in the flytower who helps them up out of the flying rig.

Dylan was first inspired in the theatrical arts when he was growing up in a Waldorf school. Each year they would do a school play but he had no desire to be onstage. His step-father was a film-maker and that inspired fifth-grader Dylan towards the backstage, triggering a forty-year love affair with technical theater. He spent a few seasons at Summer Repertory Theater in Santa Rosa, he has been technical director at Cal Shakes, the head carpenter at Berkeley Rep, a mechanic in the ACT scene shop, and even a stage manager along the way. In addition to his work on the stage here at the War Memorial, he is also the Assistant Shop Foreman at our scene shop in Burlingame, where he is responsible for the layout and flow of projects in addition to doing a lot of the metalwork and woodwork. You can see him in action welding the scenic trucks together for Tosca in this prior Backstage with Matthew post.

Dylan loves the repertory nature of San Francisco Opera. As he notes, we are one of the only companies now left in the Bay Area where we are regularly changing from one show to another, and he loves the choreography of work that that entails. In a prior job he used to use Looney Tunes soundtracks for night-time scenery turnarounds, and would know how the timing of the scenic turn was going, based on whether things were happening at the right time with the soundtrack!

The wings in It’s a Wonderful Life are such a magical part of the production and, as with all magic, there are very specific things happening behind the scenes that help us enter into this world of fairy tales, transporting us into a shimmering place of hopes and dreams. I cannot wait for you to experience this beautiful story, told with lyricism, heart and all the magic of live theater.