Backstage with Matthew: Hats Off to Tosca!

Costuming is so important to creating the very specific world of Tosca and 1800 Rome: in the detail of the fabrics, in the cut of the dresses and in the tailoring of the coats, you learn so much about society at that point in time. Between Tosca and other productions this fall, our costume shop is tailoring some 150 garments! But another important expression of society, particularly in this period, is what people were wearing on their heads. Hats are an integral part of the visual world of an opera like Tosca, and I wanted to give you a glimpse into the amazing artistry, technique and work that goes into creating hats for a new production like this.

Paula Wheeler is our wonderful Senior Milliner. She’s been here since 1992 when she began working with the then head of millinery, Charles Batte. Paula was looking to get into the fashion industry, having a certification in pattern drafting and design from the College of Alameda, and very strong sewing skills. One of her classmates was in the wardrobe union and let her know of a millinery opening at San Francisco Opera. She didn’t have a theater background but her skills were perfect for a job that requires you to take two dimensional designs and translate them into three dimensional objects, and with sewing so fine that it is imperceptible. Charles continued as head until 2000, and then Paula was promoted to Senior Milliner.

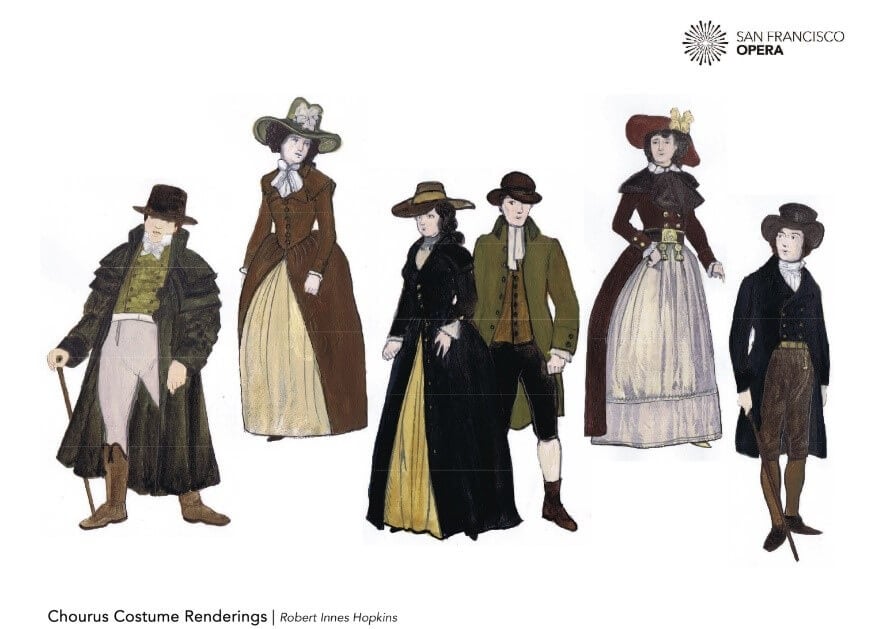

Tosca is a relatively hat-heavy production, particularly Act I and the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle. Director Shawna Lucey and designer Robert Innes Hopkins are looking to create a broad swathe of society within the church, and so costumes need to reflect a diversity of wealth, of styles, of people. Hats will be critical for both men and women, but Paula is almost exclusively focused on the women. The men’s hats can generally be purchased pre-made: there is a much larger market for men’s hats (e.g. for reenactments), and it doesn’t make economic sense to build them from scratch. They may just need different color trim (ribbon) or some simple adjustments. But women’s hats of this period are almost impossible to purchase, and must be made from scratch. A big reason for this is that women’s hats in 1800 did not fit on the head – they perched on the head, or more likely the wig. They have to be attached with a complex system of pins, and there is very little interest in wearing them now, even for reenactments. Hence, Paula taking on the building of almost 30 exquisite ladies’ hats.

Before I continue, here’s a brief glossary of hat structure, which I was happy to receive from Paula! The crown is the vertical part of the hat – think of the cylinder of a top hat. The brim is the horizontal element. And the trim is the decoration – the ribbons, feathers, buttons, etc. Okay, with those few terms under our belt, here’s how hats are made:

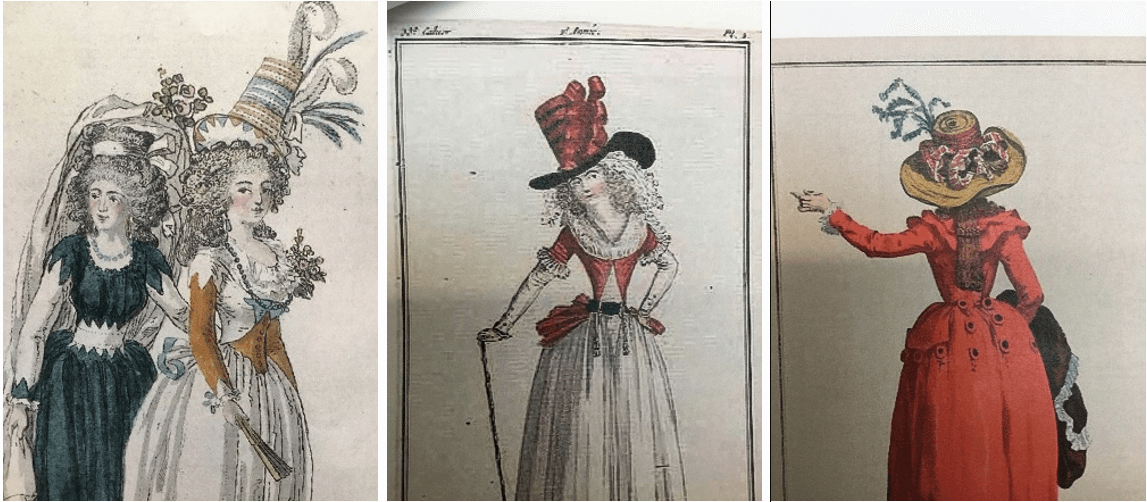

First, Paula began working with designer Robert Innes Hopkins to determine the aesthetic approach: the shape of the crowns, the size of the brims, the style of trim (which will vary by social class from a very simple ribbon to an elaborate series of bows and feathers). They came up with an aesthetic palette and Paula made a few basic sample hats to ensure they meet Robert’s aspirations. Once the aesthetic language has been agreed upon, Paula then goes forth and crafts variations within that language, changing elements to create the diversity of society we want to reflect onstage. Some hats will have slightly conical crowns, some will be straight up and down, some will taper away, some will be taller, etc. Paula researches period styles using her extensive library of costume materials, as well as resources like Pinterest.

Paula mentions that this turn-of-the-century period, coming almost a decade after the French Revolution, marked a resurgence of hats. The world of Marie Antoinette was much more about the wig itself being the focal point, with bows and ribbons directly adorning extravagant wigs. But by the end of the eighteenth century wigs were becoming more modest, and female attire, influenced by men’s military fashions, showcased large and tall hats and tailored “jackets,” or redingotes.

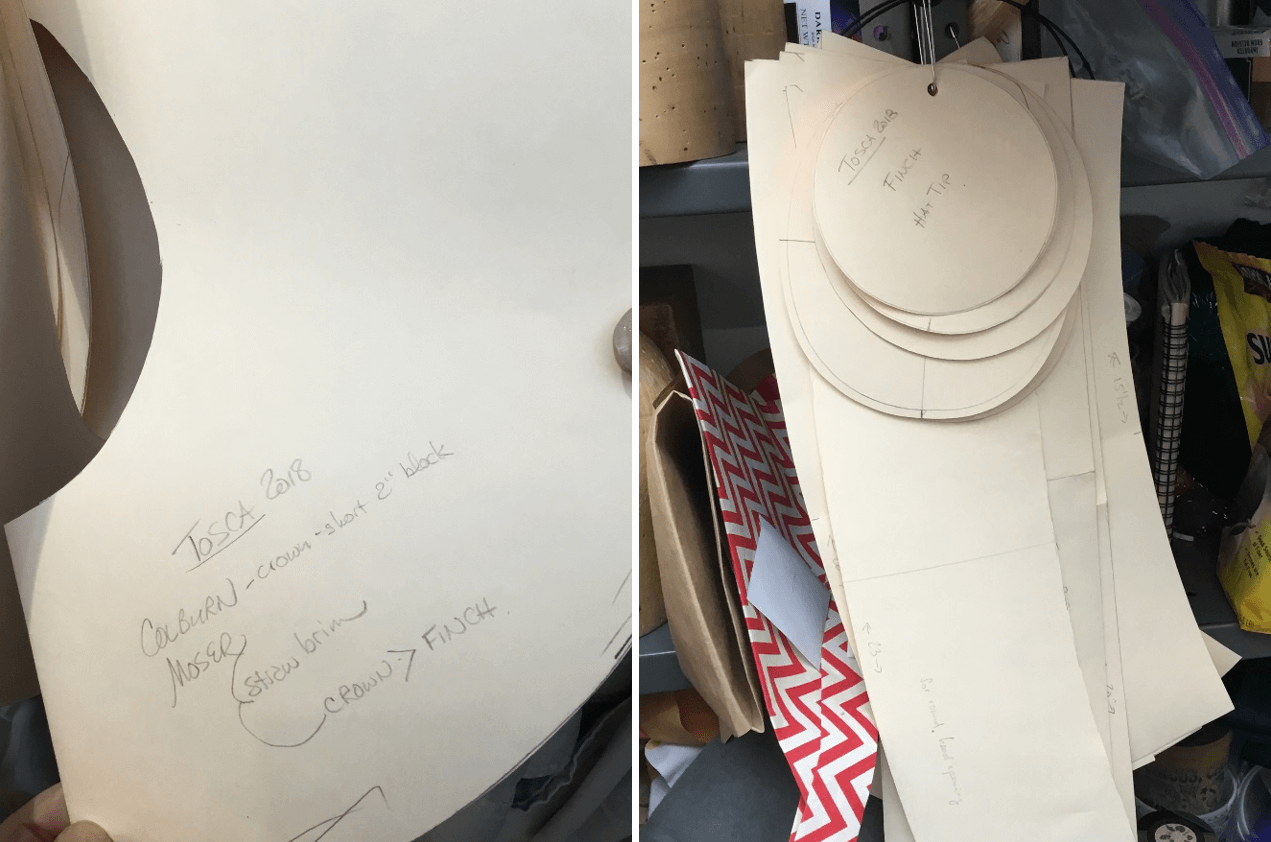

Paula creates a series of patterns for the crowns and the brims. These patterns can be utilized for a number of hats, although some become more specialty designs with their own specific patterns. Unlike a later hat which would be designed to sit fully on the head, Paula doesn’t use the wonderful array of wooden head blocks in the millinery shop for these Tosca hats. Because these hats are designed to be pinned onto the wig, the crowns are smaller than the wearer’s head.

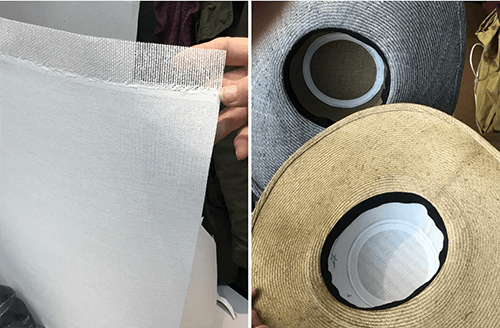

The crowns are first made out of buckram – a stiff 2-ply fabric that, once wired, creates a very stable inner core. (While making some of the straw hats, Paula also used stiffened burlap at times for the crowns as another crown base option as you can see below. Buckram is not as readily available as it used to be.) Wire is then added, stitched to the edges, to further create and maintain shape, and then a strip of bias fabric is wrapped around the edge, enclosing edge and wire to provide a surface to stitch to that will not show on the outside. A layer of flannel is then applied to smooth over any obvious bumps in the internal construction of the hat. Without this rigid stability, the hats would not have any visual durability and would look quite sad after one production run.

Once the structure of the crown and the brim are created, the fabric is then added. This is usually silk and it comes in two major varieties – faille, which has a tight ribbed weave, and then dupioni, which has elements of the raw silk coming through and is lighter weight and a little more textured. The sewing of the fabric has to be done very finely, with edges bound over so that stitching cannot be seen.

Finally, comes the trim, and for these hats, the decoration is a serious business. Paula actually makes much of the ribbon that is used – it is actually cheaper to make the ribbon out of silk, than to purchase it, particularly when specific colors are needed. Ribbon sources are dwindling these days. Finding specific colors, weaves, and widths takes a great deal of footwork and time, often to no avail. The silk is cut into the desired width and then Paula finishes the edges with a baby-lock – a sewing machine that can create a very tight edge stitch.

Bows are created with an internal layer of stiff netting that helps keep the structure of the bow, and then Paula lets her creativity loose as she brings to life hats with a variety of designs and features. The one below is a particularly intriguing trim that is designed to lift one side of the hat up with bows (the brim edge is wired to ensure the shape doesn’t collapse!). Again, a lot of research goes into this, finding historic sketches and paintings that guide the style and shape of the bows.

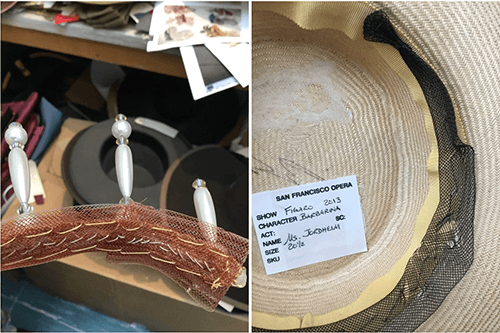

Finally, comes the attachments for the hat pins by which the hat will be secured to the wig. Hat pins can be inserted into traditional thread loops inside the hat, but it is very hard to use these loops and they don’t work well for a theatrical context when a hat may need to be attached quickly (e.g. in a quick costume change). So the theatrical technique is to apply a strip of synthetic horse-hair braid to the inside of the hat, through which the hairpins can travel on their way through the wig into the wig cap, securing the hat to the head. It’s an amazingly rigid substance, and is stitched into the inside of the crown such that it’s nearly imperceptible. The example of the braided horse-hair below comes from one of Queen Elizabeth I’s headpieces in Roberto Devereux.

At this point in the process, some two months before the opening of Tosca, Paula has about 9 hats still to make, and each one takes around 2-4 days. Some of the hats have already been tried on in preliminary chorus costume fittings, allowing for refinements to be made. The hats will likely be stored on the wig blocks during the production, but will be stored carefully in boxes once the production leaves the stage.

Paula brings a great wealth of millinery techniques to the Opera, with the huge variety of hats that we produce and work with requiring different approaches. She showed me a “puzzle hat block” which was used to create some of the hats in Aida: a wonderful wooden structure over which you stretch felt, let it dry, and then extract the wooden block by taking apart its intricate design.

She mentions the hats in Merry Widow as one of the most elaborate undertakings. She had 8 milliners working under her for this production with the huge hats requiring unbelievable amounts of decoration. And then Dream of the Red Chamber with its delicate metal hair ornaments. Hair decoration also falls under Paula’s jurisdiction, and she works closely with our Senior Craft Artisan, Jersey McDermott, who takes care of the repair and maintenance of such metalwork. The large wigs in our most recent Don Giovanni were also Paula’s creation, assisted by Lauren Cohen. Because they were more stylized hair-pieces than wigs (think small versions of Beach Blanket Babylon creations), they fell under Paula’s jurisdiction as well, and each took around 3 weeks to make!

The artistry, the skill, the finesse that is going into these Tosca hats is indicative of the love and care that is behind every element of this beautiful new production. Every element is being built to draw us into the historic world of 1800 Rome and the themes of beauty, power and corruption that underlie this amazing opera. But every element is also being built to last for decades and these hats are no exception. The techniques and care that Paula is bringing to every single one will ensure that these beautiful creations remain a part of our world for many, many years to come.