Backstage with Matthew: All Change Above

In the last two weeks, a once-every-two-year event took place: the replacement of all 588 light bulbs in the Opera House chandelier, one of the great icons of this beautiful building and, since 2006, the logo for San Francisco Opera. It’s a mammoth undertaking over 2 days and involves clambering up into the innermost secret hideaways of the building. It allows for a rare glimpse into this most monumental of structures, a glimpse I wanted to share with you this week.

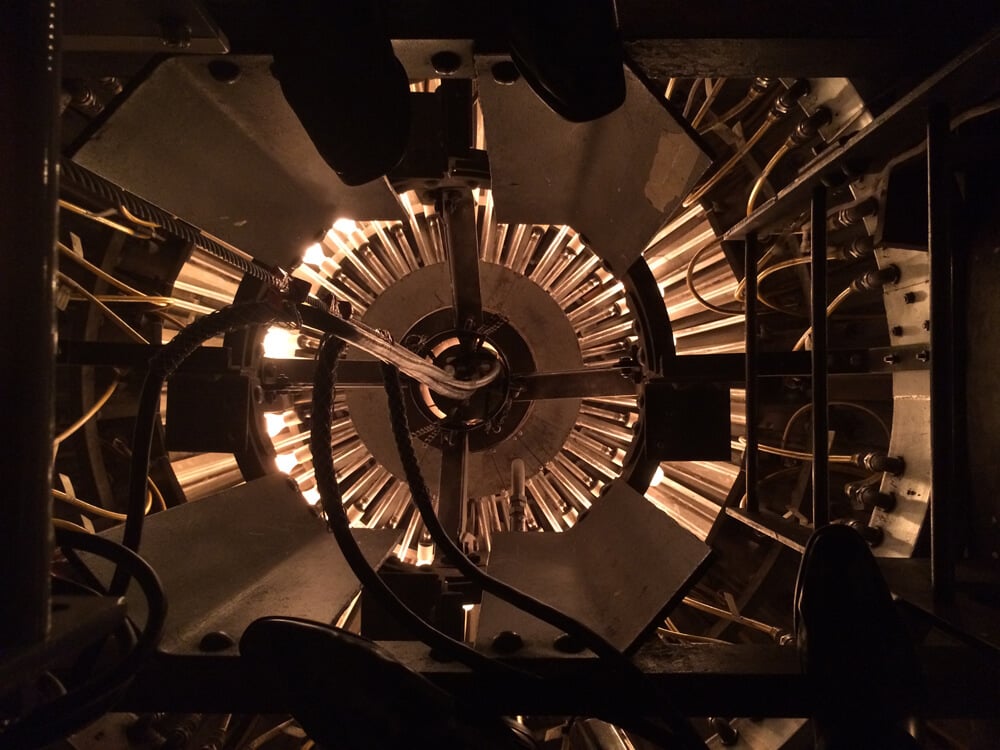

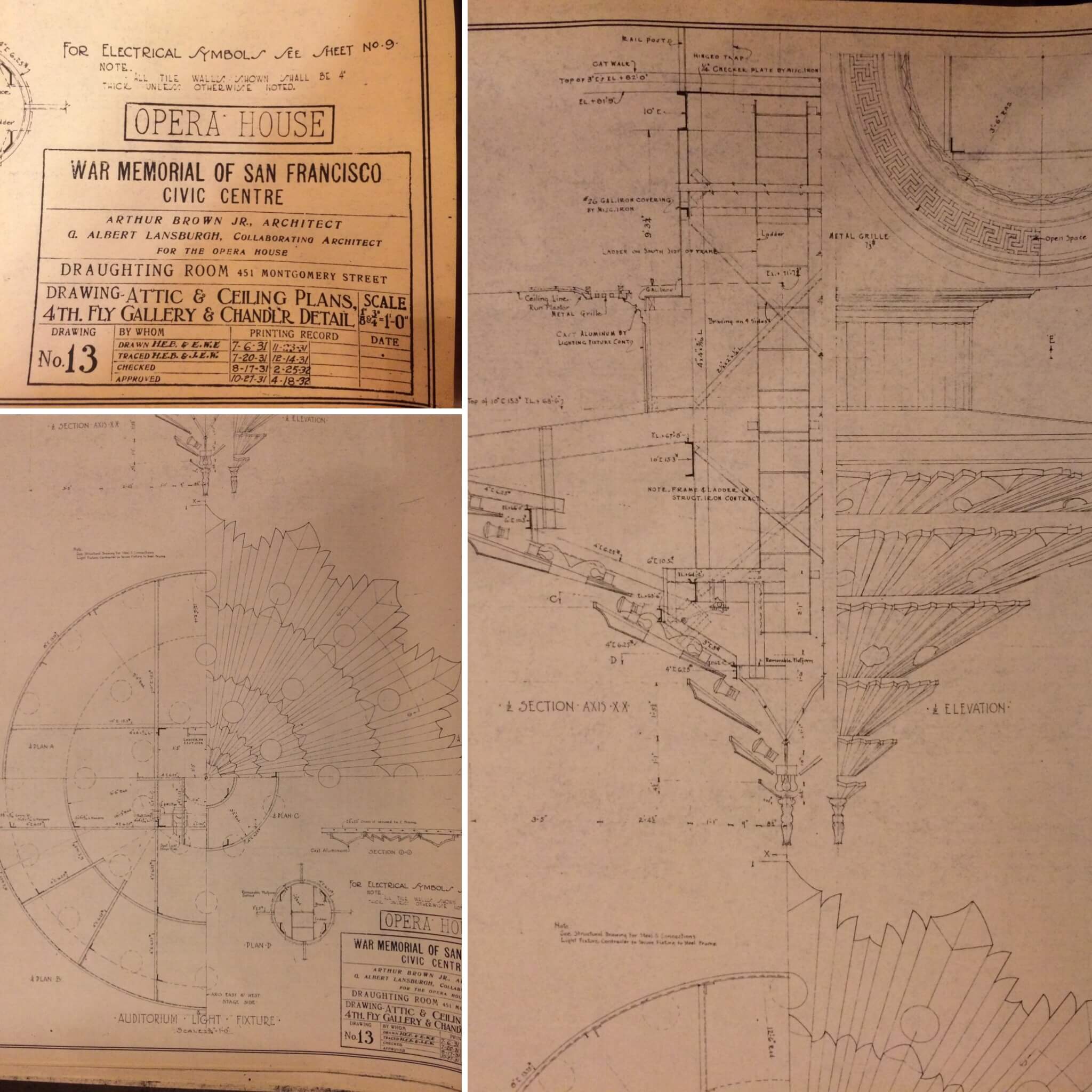

Maria Mendoza, Rolf Lee and Paul Measom undertook this mammoth light-bulb change under the supervision of the War Memorial House Head, John Boatwright. The majority of the bulbs are changed from within the chandelier itself and John kindly took me for a tour inside the chandelier so I could get a taste for what is involved. From high up in the fly tower, you access the catwalks above the ceiling of the auditorium, passing through some infamous ghostly haunts (the subject for a future backstage email…) and on towards an innocuous metal hatch. Down inside the hatch is a ship’s ladder of about 20-or-so steps that takes you right into the heart of the chandelier. Step by step you descend into something that looks like a 1930s movie-take on a sci-fi alien craft—an interplay of wires, aluminum infrastructure and a beautiful array of slightly cloudy, 100 watt bulbs. It is here that Maria, Rolf and Paul crawled around replacing every bulb—a bruising, dusty and thankless job—thankless until you pop out of a hatch onto the top of the chandelier and have what must be the most unique view of the Opera House.

The final part of this intricate endeavor is to replace the bulbs in the tip of the chandelier—a place that is too fiddly for anyone to access. The solution? The tip lowers all the way to the ground where the bulbs can be easily accessed. Originally it was lowered by a hand-crank but, at 1,500 winch turns, it was not exactly efficient. In more recent years, an electric winch was installed and now the whole thing is a much more straightforward affair! The pictures of the lowered tip are some of the most thrilling I have ever seen of the Opera House!

The chandelier is fascinating. Designed by Arthur Brown Jr., who designed the Opera House, Veterans Building and City Hall, it was the first use of aluminum in an architectural feature anywhere in the world. There are 6 levels in the chandelier, and it is attached to the I-beams of the building. It pulls 60,000 watts of electricity and has its own dedicated air-conditioning system to cool it. A little-known fact is that it originally had white, red, blue and amber bulbs, and each color could be controlled separately—one can only imagine the fun lighting designs that were had, particularly on opening nights of the season! Now, all the bulbs are white, but we do still have a little fun, with a programmed fade out of the bulbs that happens at the start of every performance (see the video below!). The bulbs are set in 32 x 20-amp circuits, allowing for this kind of customization.

John Boatwright in his office; lower pictures: controlling the house chandelier in more modern ways.

Every night, when the audience, performers and crew have left the building, John (or his colleague Gail Ashworth) has a part-ceremonial, part-safety role to close down the stage. He walks out the ‘ghost light’—a historic light intended to either ward off ghosts, or invite them to the stage, depending on your personal superstition. (It also has a beneficial secondary function of ensuring no-one falls into the orchestra pit!) There’s something very heartening knowing that John bids goodnight to the stage each night, the glow of his ghost light just faintly catching the reflective aluminum of the mighty chandelier, towering many feet above.

So next time you look up at the chandelier, give a thought to those who have to change the light bulbs every few years: that aluminum cone is a portal into a world of mystery above.