From Small-Town America to the World Stage, Opera Legend Simon Estes Shares His Journey

Estes felt like he had hit the jackpot. “That was like a million dollars to me then,” he recalls.

With his father having recently passed away, the money was all the more vital. Estes had the responsibility of supporting his mother as well as himself. So he was excited to share the good news with her. “Mother, your worries are over now,” he remembers declaring over the phone.

He hadn’t realized, though, that his pay would not stretch as far as he had hoped. He had to pay taxes on that income. He had to pay his management. He had to pay for his own flights and hotels—and that of his accompanying pianist too.

“I remember I ended up in debt that year,” Estes says with a laugh like rolling thunder. “After I thought I was John D. Rockefeller, making $25,000 a year!”

But it wasn’t easy trying to make it as a young singer in the opera industry—especially if you were a Black man in America. Estes knows this all too well.

Even as he performed for presidents and popes—for Olympic ceremonies and sold-out opera houses—Estes says he never earned what he should have been paid. It was always a struggle to command the same salary, the same respect and the same recognition afforded to his white colleagues.

And yet, if there’s one message Estes hopes to send as he prepares to fly to San Francisco this month to film a documentary about his life, it is one of hope. His story is one of hardship, certainly. But Estes himself has resolved never to be bitter. He sees better things to come.

“I hope the day will come when—what Martin Luther King said—you will be judged by your character and not by the color of your skin. I hope people will be treated equally regardless of their skin color or their nationality. That they will be paid decently, like they should be.”

It is in that spirit that Estes shares his story: a tale of great triumph and great tragedy, of great faith matched by great courage.

Before Estes became one of the leading bass-baritones of his generation—a voice known for its Wagnerian might—he was a young singer growing up in Centerville, Iowa.

The city’s bustling coal industry had brought his father to the area. A son of an enslaved man sold for $500, Estes’s father had served in World War I. He never learned to read or write. But he and his wife, a Centerville native, instilled in Estes and his three older sisters the importance of study.

“My dad always said, ‘Son, get an education. That's something they can't take away from you,’” Estes recalls.

Estes imagined he would one day study to be a doctor. Growing up on East Jackson Street—in a little house no bigger than 27 feet by 25, with no electricity or running water—Estes remembers looking up to the doctors, ministers and teachers in his community. He credits them with fueling his strong sense of community service.

But it was in church that Estes found his voice. A deeply religious man, Estes credits God for his talent, and there, in Centerville’s historic Second Baptist Church, he delivered his first solo as a boy soprano.

“I just sang. It was just very, very natural,” Estes recalls. In his elementary-school music class, his teacher recognized his talent, too. She had him sit in the front of the class.

Then, when he entered junior high, the high-school choir director scouted him to perform with the older students. He remembers the mother of one of his classmates, a Mrs. Poffenberger, bursting into tears as he performed.

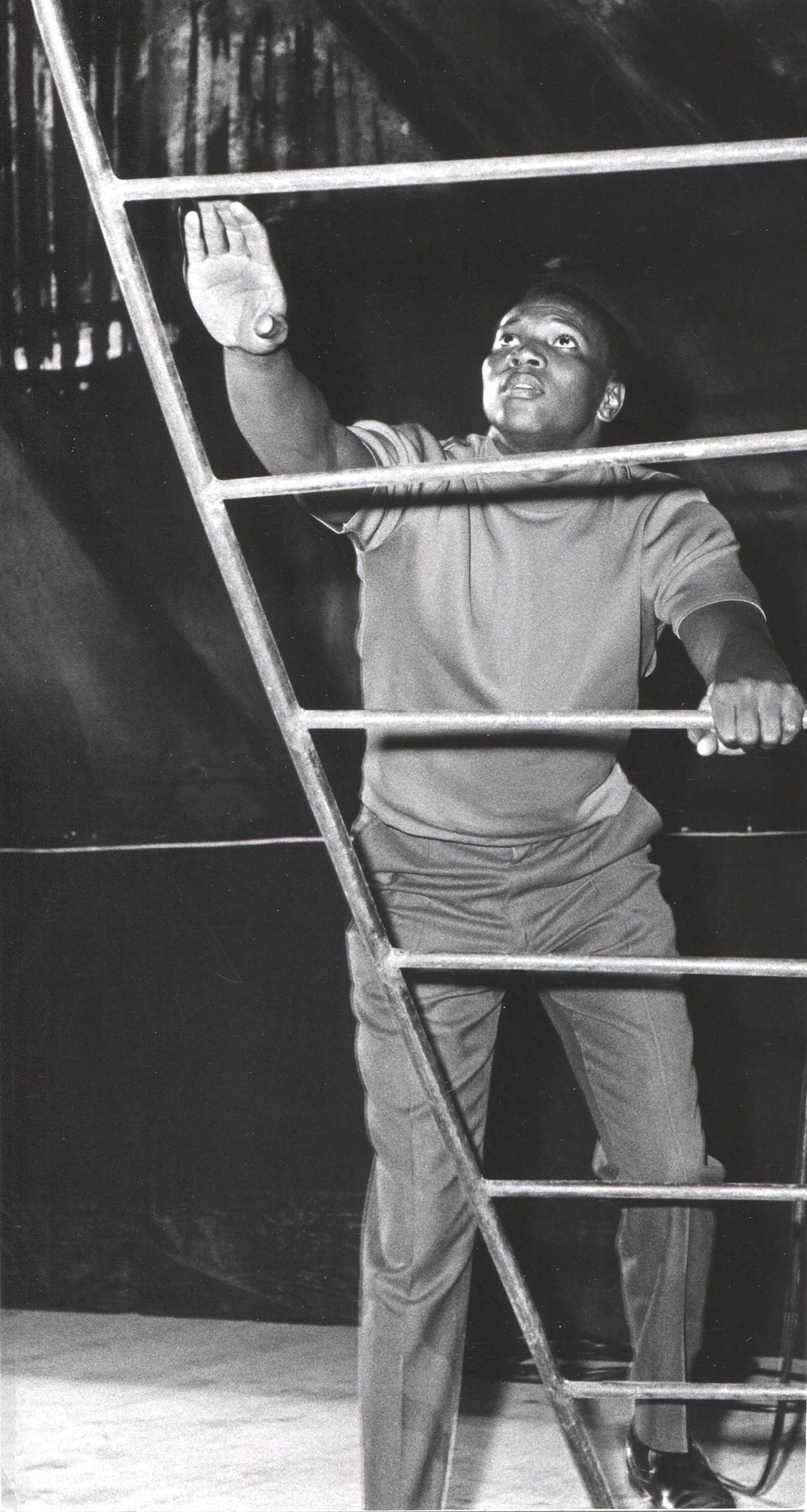

The angelic sounds of his soprano voice gradually gave way to the low, elemental rumble of a stout bass-baritone, powerful but smooth. Still, by the time Estes entered the University of Iowa, he envisioned himself following a pre-med track. It didn’t occur to him that his voice was extraordinary enough to pursue a career.

Still, he kept singing. Estes was the first Black man to perform with the Old Gold Singers, a choral group named for the university’s colors, gold and black. He could deliver a deft imitation of Nat King Cole, a skill that proved useful when performing the group’s pop-music repertoire.

But Estes longed for more. The university choir was the most prestigious singing group on campus, and one day Estes decided to approach its director, a professor named Harold Stark, about joining.

“May I sing in the choir?” Estes asked. He remembers Stark replying, “Oh no, no, no, your voice isn't good enough.” Estes then asked for voice lessons. Stark’s reply was the same.

“You have no talent.” That was the message Estes came away with. But while Stark refused to mentor him, he did point Estes toward a colleague arriving that fall in 1961: a young Greek American professor named Charles Kellis.

Estes later learned that Kellis had been impressed by his voice. He had heard it resounding through a door in the music building.

That fall would prove to be a turning point in Estes’s life. On October 10, his father died of a ruptured appendix at age 70, under circumstances Estes believes were preventable. Doctors dismissed his pain as a heart condition, and when Estes asked for a closer examination, he was told his father was going to die anyway.

“He died because of basically racism,” Estes says matter-of-factly. Still, rather than be bitter, Estes emphasizes that he chooses prayer over hate. He looks to the positive, “I'm so happy my father lived long enough to know that I was at the University of Iowa getting a university education.”

It was around that time that Estes was on the precipice of discovering his life’s work. Kellis, his new voice teacher, introduced him to opera for the first time, playing vinyl records from artists like Cesare Siepi and Maria Callas.

Somewhere amid the Leontyne Price album and the recording of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, Estes had come to a realization. “Oh, I really like that stuff,” he exclaimed.

“I had not heard classical music at all” before that time, Estes explains. But now, looking back, Estes can see how the sounds of opera recalled the sounds he heard at home: in his oldest sister’s beautiful voice and his mother’s incredible singing range. They too had the talent for opera, he says.

“I look at it this way,” he explains. “It was always inside [me], but I hadn't had any exposure to this type of music. And so once my ear heard this and transmitted the sound and everything to my brain, I just said, ‘Wow, I really like that stuff.’”

Kellis guided Estes in his first steps toward becoming an opera singer, ultimately arranging for Estes to audition for the world-famous Juilliard School in 1963.

“I had never been on an airplane or anything,” Estes says. “I worked and earned the money to fly out there.”

But his studies at Juilliard would be cut short by an unexpected opportunity. Christmastime was approaching, and Estes was eager to visit his girlfriend, a Juilliard student who had graduated and moved to Germany.

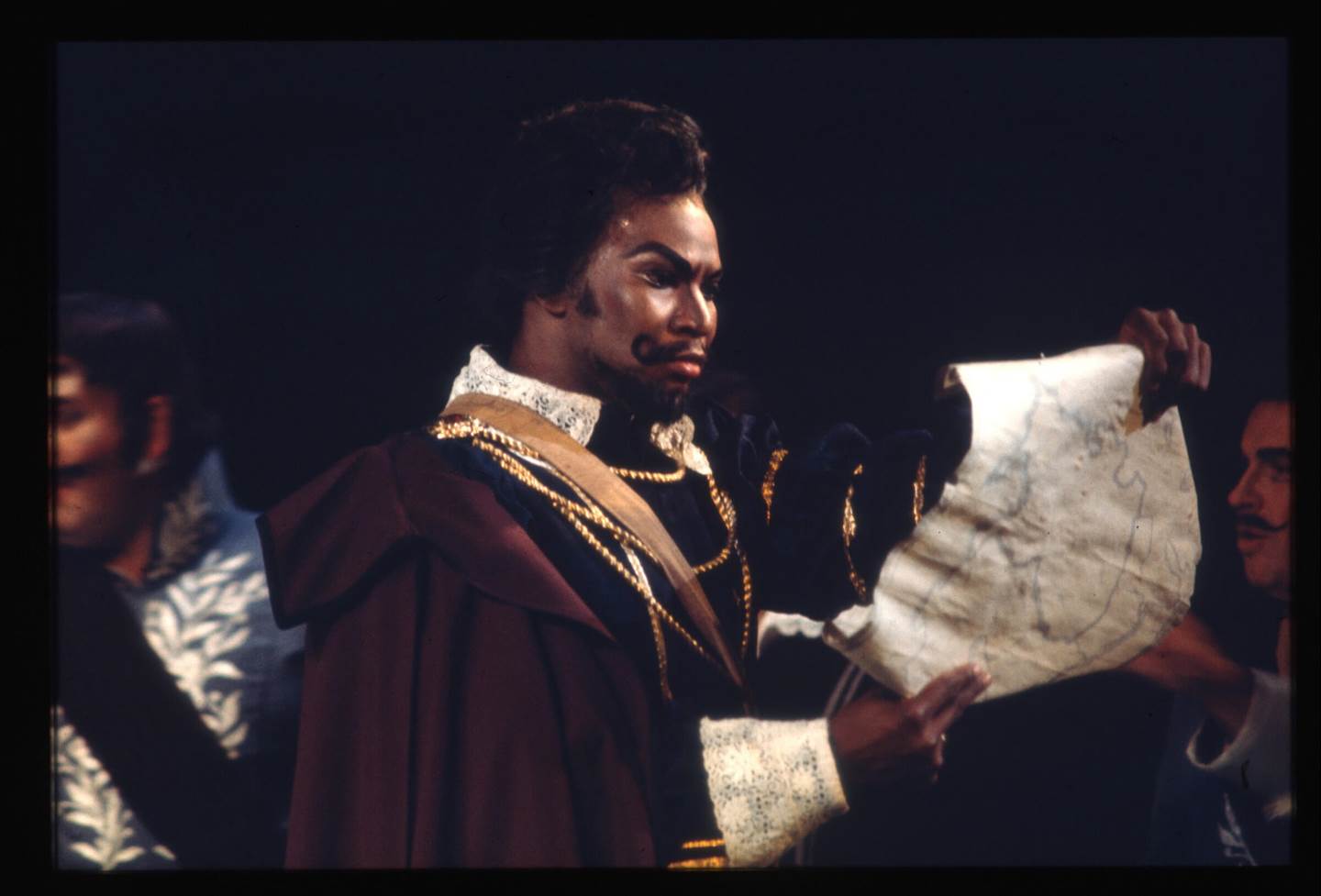

So he decided to travel to Europe to audition for an agent, knowing he could meet his girlfriend while he was there. Estes arrived in Düsseldorf on Christmas morning. A couple days later, he was singing for the casting agent. Estes’s voice impressed the man so much that Estes was cast in a 1965 spring production of the opera Aida at the Deutsche Oper Berlin.

Estes returned to Juilliard, thinking the school’s dean, Gideon Waldrop, would be delighted to hear of his casting coup. Instead, Waldrop warned Estes: If you don’t finish Juilliard, you may never have a career in opera.

It was a risk Estes was willing to take. Something inside of him told, “Go east, young man.” And he did.

But the decision came with hiccups. Estes had worked hard to learn the role of king in Aida, only to discover, upon his arrival, that he would instead be singing Ramfis, the high priest who opens the show.

With days until the first performance, Estes worked with coaches at the Deutsche Oper to learn the role. “Not only did God give me a talent to sing, he gave me a talent to memorize. And I memorized Ramfis in those four or five days,” Estes recalls.

By the time the curtain rose on that 1965 Aida, Estes was ready to sing the role—but he had never rehearsed with any of the opera’s stars or its conductor. He had to navigate the stage based on the barebones instructions an assistant director had given him.

The conductor, Giuseppe Patanè, approached him after the show. “Nobody told me you’d never sung the role before, that you were a beginner,” Estes remembers him saying. But Patanè reassured him: “You did alright.”

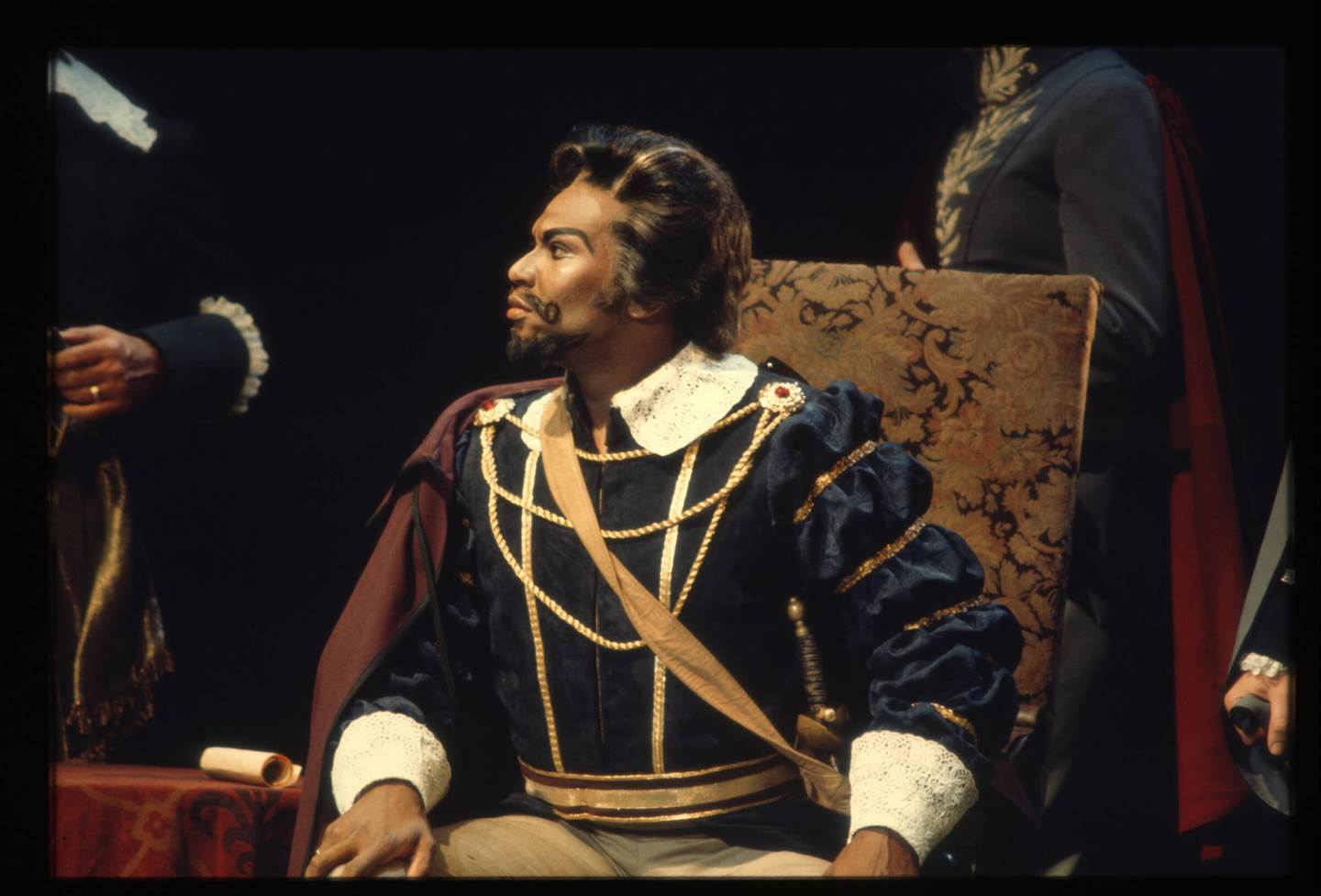

It was the start of a bustling career for Estes in Europe, one that would eventually lead him to become the first Black man to star at Bayreuth, the famed festival founded by composer Richard Wagner. He would tour the continent, singing lead roles like Timur in Turandot and Boris in Boris Godunov.

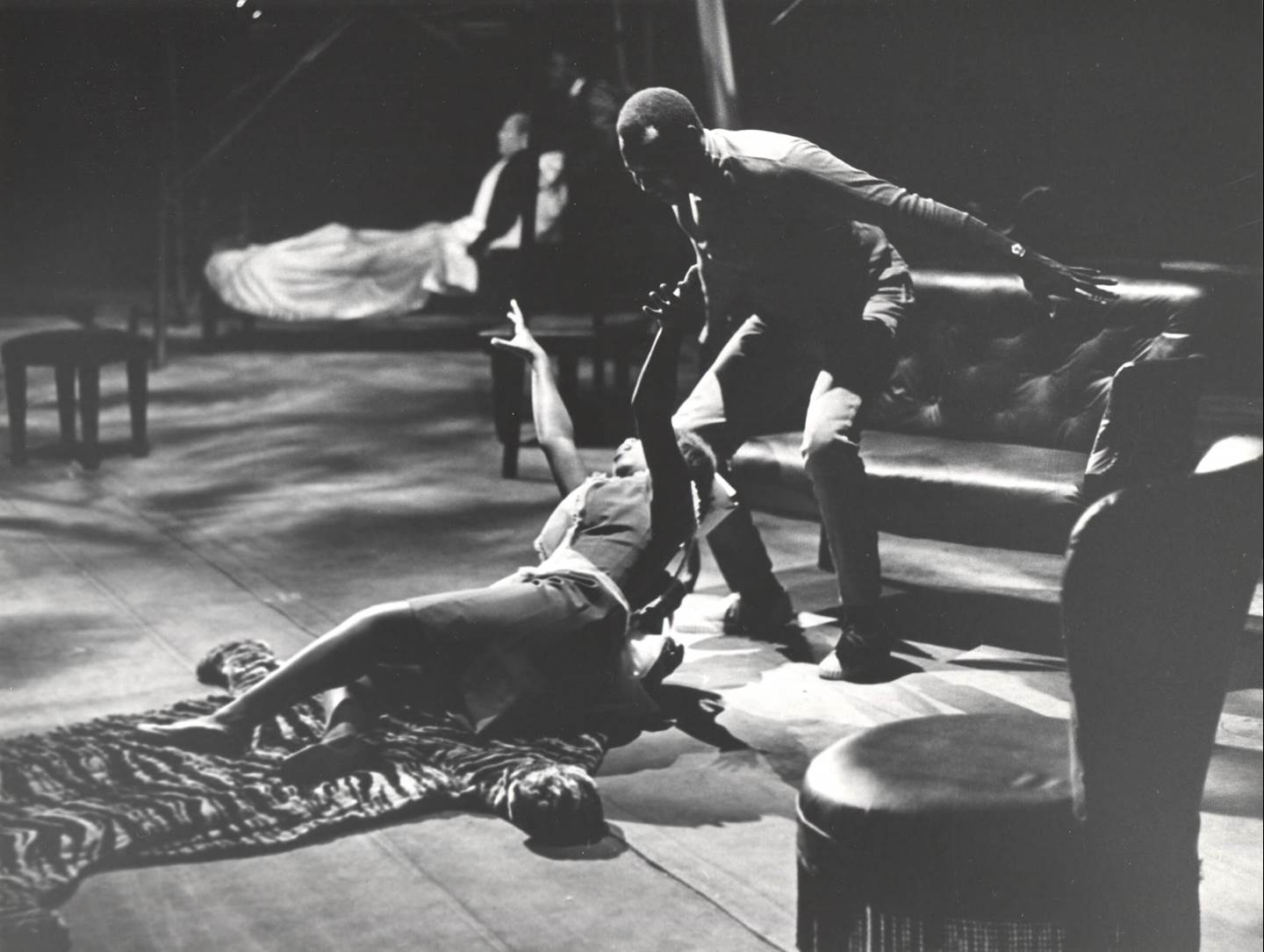

But in the United States, the path to success was riddled with barriers. Racism was rampant, and few opera houses were willing to hire Estes, in spite of his high-profile successes in Europe.

“I’m not ashamed to admit I was in tears,” Estes says. He remembers calling his mother for advice. “Mother, I’ve sung in Vienna and Berlin and Paris and London,” he said. “But they won’t engage me in my own country in opera houses.”

Her advice? “Well now, son, you get down on your knees and pray.” And so he did.

His big break came in the form of fearsome Viennese conductor by the name of Kurt Herbert Adler. As San Francisco Opera’s second general director, Adler undertook a campaign to transform the company into a world-class destination—and he did so by scouting new talent, making San Francisco the place to go to hear the next big opera superstar.

“Kurt Adler was the first one who engaged me, and I will always be grateful,” Estes says.

He started out in 1967 with the company’s affiliate program, the Spring Opera Company, playing the four villains in The Tales of Hoffmann. But by autumn of that same year, Estes was starring on the main stage. He performed the lead role in the U.S. premiere of The Visitation—an opera he had helped originate in Europe—and then went on to sing La Bohème, opposite Luciano Pavarotti and Mirella Freni.

It was the beginning of a relationship with San Francisco Opera that would span more than a decade. But in those early days, Estes quickly realized he was not earning as much as his co-stars, who could net five-digit paychecks per performance.

Estes found himself on a weekly contract, one that he estimates came out to about $257 per show. He felt the injustice of his circumstances acutely. But Estes resolved to “swallow [his] pride,” as he puts it, and complete the contract. He knew his management would make hay of his starring opposite big-name artists like Plácido Domingo, Shirley Verrett and Beverly Sills.

“As a Black man—in my whole career, almost 60 years—I was never paid what I should have been paid in all the opera houses, even all around the world. They just wouldn't pay,” Estes says.

Though his salary got slightly better as the years progressed, Estes believes the disparity boiled down to questions of racism and gender. “They didn't want a Black man playing opposite a white woman,” he explains. “But a white man can sing with a Black woman.”

But backstage at San Francisco Opera, Estes received encouragement from an opera icon: famed soprano Leontyne Price. She was in San Francisco in 1981 to star in a different opera—La Forza del Destino—when fate thrust her and Estes into the same show.

The star soprano of 1981’s Aida fell ill, and Price was asked to step in. It was one of her signature roles. Estes was scheduled to play her father, Amonasro.

“When I was singing the duet with her—the Aida and Amonasro duet—tears just started rolling down her face. And she said, ‘Simon, you sound like a Black god.’ I never will forget that,” Estes says.

Bigotry, unfortunately, remained a through-line in Estes’s career: He chuckles that he could tell stories about it for hours. There was that time he was accused of stealing a white woman’s jewelry. That time when a highway patrolman tailed his car from the airport to his hotel. That time he endured vile racial epithets while sitting in a restaurant, peacefully eating his meal alongside his white accompanist.

But always, Estes returns to his message of hope. He is 84 years old now and still singing, with teaching gigs and philanthropic efforts to boot. This summer, he returns to the stage as the lawyer Frazier in Des Moines Opera’s company premiere of Porgy and Bess. The gig comes 37 years after he helped debut Porgy and Bess at the Metropolitan Opera.

Most singers are retired by his age. But even after six decades of professional singing, Estes believes his voice is testament to a greater power: “It’s God singing through me.”

And for all the wrong done to him, as he contended with a racially divided America, Estes is determined to follow the example set in the Bible: “You turn the other cheek.”

He knows that path isn’t for everyone. But for him, it has helped. Estes remembers a concert in San Antonio, Texas, where he was approached backstage by a retiree who had taught at the University of Iowa. It was Harold Stark, the same choir director who had once dismissed him as a singer of no talent.

But rather than flaunt his accomplishments or make Stark eat his words, Estes accepted his handshake. He remembers Stark saying, “I see you’ve done quite well for yourself.” Estes thanked the man and watched as he walked away.

Nothing else was said. Nothing else was necessary. Estes didn’t have time for any bitterness or hate. After all, he had more stages to sing on, more students to mentor, and a world of difference to make.

Legendary bass-baritone Simon Estes returns to the opera stage this summer in Des Moines Opera’s Porgy and Bess. Find out more here.