Tenor Russell Thomas on Reimagining ‘Fidelio’ and Leading the Opera Industry

When COVID-19 shuttered theaters in spring of 2020, Thomas—one of today’s most in-demand American tenors—found himself, like many artists, faced with cancellations. His globe-trotting career came to a grinding halt.

“It was a very scary time for a lot of artists,” he says. “The idea that I wasn't on a plane scared me because that means I'm not making money. If I'm sitting at home, as much as I valued that time being at home with my family, that means I'm not earning money.”

Still, Thomas considers himself lucky. He was able to support himself and his son through the closures. And yet, the anxiety of not knowing when the next paycheck would come lingered. Thomas observed it in his opera-singing colleagues, too.

“The pandemic scared the shit out of us,” he says with disarming frankness. “And then when everything opened back up in May, before Delta [a COVID variant] came out of the woodwork, we were all just saying ‘yes’ to everything.”

For Thomas, that meant singing three roles in about three and a half weeks, he says. The stress was beyond what he had ever experienced before. Cancelled and tentative projects were suddenly back on the calendar—all at once.

One of the productions, Los Angeles’s Oedipus Rex, involved an opera he had sung only once before—a decade ago, no less. Another, Berlin’s La Forza del Destino, required Thomas to perform one of the biggest roles in his repertory. And the third, Chicago’s Pagliacci, had transformed from a concert into a film, bringing with it a new set of demands.

“So I was learning three things at once,” Thomas explains. “And I'm not a multitasker with learning music. I usually can't do it, but I had no choice. I had no choice. It was either that or say, ‘Go find somebody else.’ And I wasn't in the financial position to say that.”

Even as he juggled the pressures of competing engagements, Thomas had other responsibilities too: He’s a single father to a young son, not to mention a professor at Indiana University since 2020. And at the start of this year, it was announced he would serve as artist-in-residence to Los Angeles Opera.

It has forced Thomas into a head-spinning schedule. One day, he might be on a red-eye to Indianapolis, only to drive an hour more to see his students in the university town of Bloomington, Indiana. The next, he might be flying back to the West Coast, where he’s currently in rehearsals for San Francisco Opera’s new production of Fidelio.

All the job-hopping has Thomas thinking about the future. “This job in Bloomington is the first time I’ve ever had a 401(k) and a job with benefits,” he says. As he looks ahead, he envisions a different lifestyle for himself, not one where he’s chasing singing gigs into old age.

“I aspire to other things: to run an opera company,” he says.

And with that, he turns back into the boy who first fell in love with opera on the radio, twiddling the dial and landing on what he later realized was a performance of Carl Maria von Weber’s Oberon. It’s his love of opera, Thomas says, that qualifies him for the role. That, and his enthusiasm for diversifying the art industry.

“Whenever there was singing, my attention was glued to that radio. And it was always that way for me with singing, even in church,” Thomas recalls. “But listening to opera for the first time as a kid, it was just the nature of the voices—that the human voice can make that kind of sound. It was miraculous to my young ears.”

It was so miraculous, in fact, that he could barely believe what he was hearing. His first live opera was a production of Carmen at the Florida Grand Opera, formerly the Greater Miami Opera. He remembers asking someone, “Where do you guys hide the microphones?” He was surprised to learn there were none. He decided he too wanted to sing with that power.

Thomas, who spent his childhood in school choirs and attending field trips to the theater, believes those types of outreach efforts are necessary to growing and diversifying opera.

“If you’re not making sure that you’ve welcomed in everybody, you’re losing out on the potential next Russell Thomas or whatever other little Black or Asian or Latino kid that didn’t think this was for them,” he says.

“If you want the art form to survive, you have to make it look like your community, the community that houses it.”

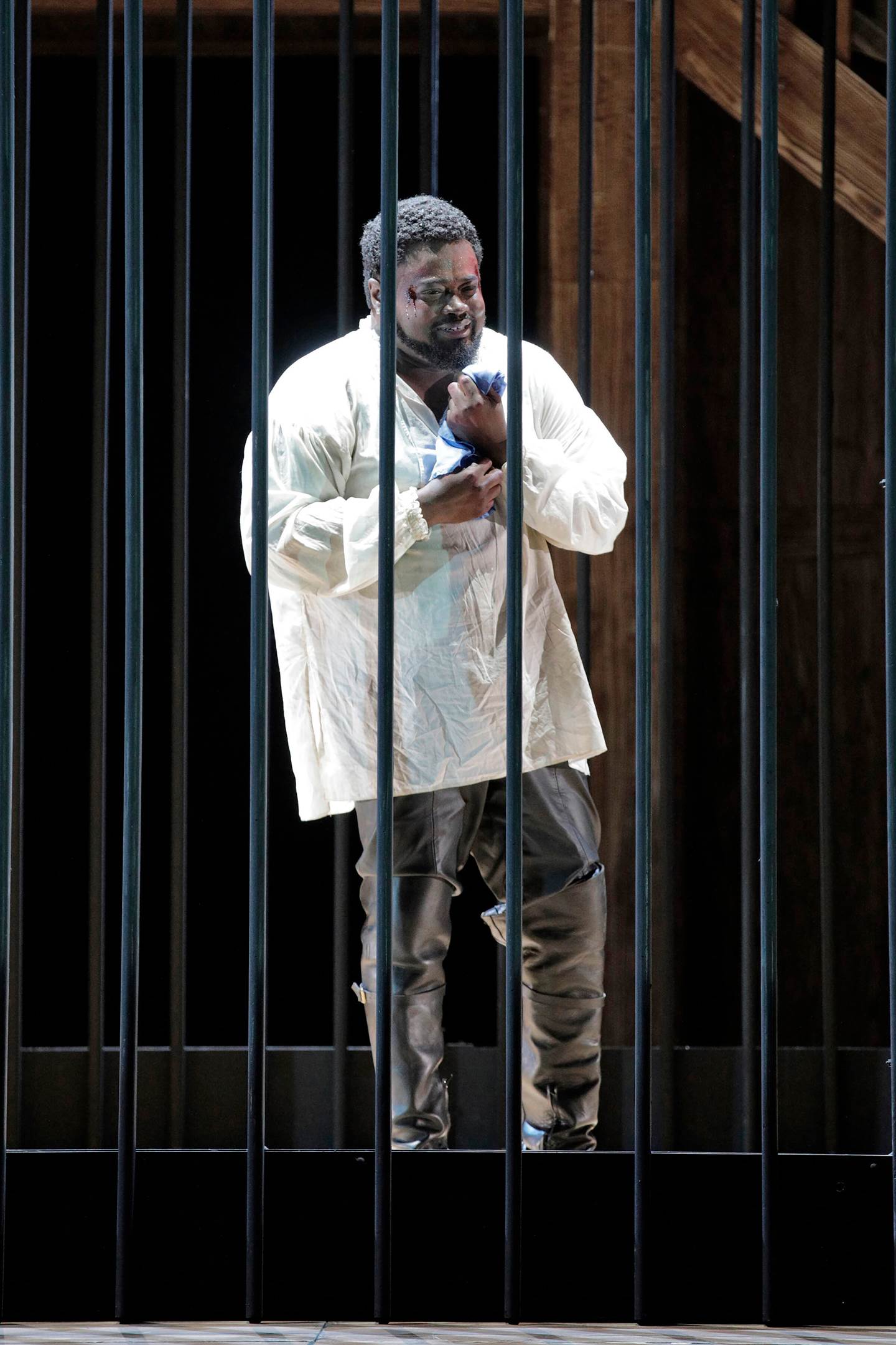

In a new interview, Thomas shares how he thinks opera can work toward that goal—and how he’s preparing for director Matthew Ozawa’s modern update of Beethoven’s Fidelio, on stage this fall at San Francisco Opera. Thomas stars as Florestan, a man secretly imprisoned in a detention center, simply for the crime of speaking out.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Can you tell me about the first time you had to sing this? Beethoven is notorious for being punishing on the vocal instrument and treating it just like anything else in the orchestra. What was the process like for you, trying to ramp up to playing Florestan?

RUSSELL THOMAS: Well, I was already a huge fan of Beethoven’s songs. I'd sung a lot of Beethoven songs in recital. And this part didn't challenge me as it does some other people, because, one, I'm not a heldentenor. So my voice probably isn't as heavy as those guys who normally sing it. My voice likes to live in the top, in the high notes. People scared me from this role, but the role itself didn’t scare me.

There are moments where it's quite challenging: the end of his [Florestan’s] aria, for instance, and then at the very end of the opera, when you're singing in the ensemble with a hundred other people and the tenor has the top vocal line and you have to soar over that line the entire time, over everybody else.

And that's the way he [Beethoven] wrote it. He wrote it for that purpose. At that point, after this character has been oppressed and held back for so long, he finally sort of lets it rip in that final ensemble. Those are the two challenging moments in the entire piece for me. Otherwise, it really is one of the easier things I sing these days. [Thomas laughs.]

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Can I ask you about the characterization itself? I feel like I have a clearer idea of Leonore and Pizarro and the other characters, but Florestan? He comes up in the second act—

THOMAS: —Out of nowhere!

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Exactly. How do you get inside someone who functions almost like a damsel in distress? He’s the motivation for other people to do their heroics or their villainy. How do you fill him with life and personality?

THOMAS: Well, for me, this piece has always been about the prison industrial complex in America and the voicelessness of those people and the invisibility of those people. No one really sees them. And when they do, they don't see them as human.

There are some people who definitely deserve to be in prison. But there are people who are in prison for crimes that were made to just lock Black men up—laws that were written on the books just to lock Black men up. And then that cycle of incarceration: From one innocent crime, your entire life becomes, “You’re a criminal.”

So I've always looked at this person, Florestan, as someone who probably did the pettiest of crimes. Again, I know that's not the story here. The story is he basically spoke up against this person in the government. [The villain Pizarro is a corrupt nobleman in the original opera.] But in order to infuse this guy with any kind of life, my story has always been about Black men in prison and how, a lot of times, they're in solitary confinement.

I've had relatives that were in prison. So it's a piece that's very near and dear to me because of just that. I think it's amazing that, 200 years later, Beethoven's commentary about the system is still relevant, you know?

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Has your understanding of the role changed since returning to it this season in San Francisco?

THOMAS: Not really. I’m happy that [director] Matthew Ozawa is updating it. I think that's great. I've always wanted to do one that was updated.

I had actually shopped an updated version of this around to a few opera companies. And they didn't want to touch it because I wanted it to be all Black men in prison. I wanted the chorus to be all Black men so they could see that the reality of what's happening in America's prisons on stage.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Do you feel comfortable with speculating why opera companies would be afraid of tackling something that would reflect the dramatic racial dynamics of American prisons?

THOMAS: Because they don't want to offend. One of the things about being a nonprofit is that you have to not piss anybody off. So I think that they shy away from doing things that are controversial.

A controversial production in opera is updating something to a different period or taking Turandot out of China and putting it in New York. That would be too much for most opera-goers.

But to actually have a political statement on stage of something happening now is something that they never want to really touch because they don't want to alienate anybody who could possibly donate money.

So everything is always a little safe or it's pretty, but it doesn't really say anything. It's wonderful when you have someone like [director] Matthew Ozawa that says, “We can't do this and make it another pretty night at the opera. We have to say something with this piece.”

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You're talking about some of the realities of working in non-profit arts: the need to court public opinion, the need to gather immense amounts of donations to keep the whole boat afloat. With all that in mind, with all the pressure, when did it occur to you that becoming an opera company director yourself was a dream that you had?

THOMAS: It’s always been an idea as long as I knew that I wanted to sing and I started to work and be around the business. I knew that, one day, this is something that I wanted to do.

Again, it’s difficult when you don't see people who look like you doing it. And it becomes a question of: Is this something that I can do? Will I be welcomed into these circles? So it's kind of a complicated situation for me as a Black man and as a Black man who sings opera.

I've seen some colleagues of mine decide on a Monday that they didn't want to sing anymore. By the next Monday they had a job, whether they had any experience in the field or not, because they were welcomed in and given an opportunity and even trained on the job. That doesn't happen for Black folks or Asian folks in this business. It just doesn't happen.

I’ve been talking about issues of diversity for more than a decade: about how diversifying the back office will diversify the stage and how diversifying the stage diversifies the audience. People ask me to talk about that, and I talk about it, and I go to their board meetings and such. And they don't really do a whole lot about it. But it's the only thing that's going to make opera survive.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You have a unique perspective in a way, because you have a young son coming up right now. How do you see his relationship to music evolving?

THOMAS: Well, it's my job as a parent to introduce him to music. We talk about Prince and Michael Jackson just as much as we talk about Beethoven and Verdi, you know? It's important for me that I introduce my kid to the arts.

He loves opera. He's loved opera before I ever talked to him about it. I'll never forget studying [composer John Adams’s opera] Nixon in China when he was probably two years old. I was watching the video of it, and he cried when I turned it off. And that's John Adams. It’s not like a tune he could go whistle to! [Thomas laughs.]

Same thing with taking him to see his first opera. He saw The Magic Flute on one of my off-night performances at the Met. When it was over, he was upset that it was over. He cried and screamed and did not want to leave the theater.

Let’s bring these kids to the theater. Let them see what it is you're doing, and who knows the effects it can have on them? That's sort of what I'm doing for my kid.

He's starting to take piano lessons. He may be shit on the piano, but it's for him to know that that's an option. Not everyone has the means to be able to do that, as I do. So it's the job of these institutions—like the symphony, like the opera, like the ballet—to reach out to these communities and welcome them in.

To hear more from tenor Russell Thomas, visit his website or follow him on social media. Thomas stars in Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, opening October 14 at San Francisco Opera.